Note on ‘From Secret Ballot to Democracy Sausage’ by Judith Brett

My notes on: Brett, Judith. (2019). From Secret Ballot to Democracy Sausage.

[This note may contain errors and inaccuracies. It was mostly written just for myself, in preparation for my live podcast conversation with Judith Brett.]

Australia has a unique voting system, defined by compulsory preferential voting. It's also world-class at running elections, which are overseen by independent non-partisan bureaucrats. How did we get here, and what does it say about our political culture?

Judy Brett's book From Secret Ballot to Democracy Sausage is probably the canonical history of Australia's voting system.

Below is a list of about 30 things I learned or am left wondering after reading this book.

(1) Australia is not just good at elections—it's been an electoral innovator.

Australia:

- Was the first nation to give women the right to stand for parliament. (p175)

- Was the first to establish a national non-partisan electoral machinery. (p175)

- Is one of about 8 countries that holds its elections on Saturdays (a measure introduced in 1911), which makes it's easier for workers and students to vote (most countries vote on Sundays—and, apart from New Zealand, which also votes on Saturdays, all the core Anglosphere countries vote on weekdays).

- Was the world's first English-speaking democracy to hold a compulsory voting election (in Queensland in 1915), and remains the world's only English-speaking democracy with compulsory voting. (p118)

- Uses a preferential voting system, whereas first-past-the-post is the norm for most English-speaking democracies.

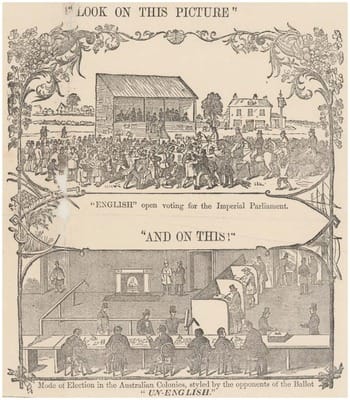

- Invented more efficient ways of implementing secret voting—the 'Australian ballot'. (p23)

- Also has centralised, continuous, and now automated electoral roll updates. (pages 74-76)

(2) Compulsory voting came towards the end of Australia's long history of electoral innovations.

It has been compulsory to vote in Australian federal elections since 1924.

But most of our electoral innovations occurred between the mid nineteenth century and the early twentieth century.

(3) Strikingly, none of the other core Anglosphere countries—the countries in the mainstream of Australia's political development—have compulsory voting.

(Those countries are: US, UK, Canada, New Zealand, Ireland.) (See p1 and p3)

(4) At the ideological level, the most common argument for compulsory voting is the majoritarian one: it imbues the government with democratic legitimacy.

Pages 177-178:

"The most common argument for compulsory voting was the majoritarian one: that the elected government should represent not just the majority of those who vote but the majority of those eligible to vote. This would increase the government’s legitimacy and make sure it paid attention to the interests of all the people. Similar arguments were put in support of preferential voting, which was introduced at the federal level in 1918. It prevents the election of candidates who win only a minority of the first-preference vote.

Majoritarian arguments for compulsory voting in Australia are a close companion of egalitarianism. If government is to deliver the greatest happiness to the greatest number, then the greatest number need to vote."

(5) Australia federated in 1901, but only got the voting systems originally intended for its two houses of parliament by 1948.

The House of Representatives adopted preferential voting in 1918.

The Senate got proportional representation in 1948.

Page 141:

"Almost half a century after federation, the two houses would now be elected as Australia’s first government had intended."

(6) I'd underrated preferential voting and the 'bureaucratic model'. They are just as important a reflection of our majoritarian political culture as compulsory voting is.

From previously dipping into the book, I knew one of its central arguments was that compulsory voting is a reflection of Australia's 'Benthamite' political culture.

On this latest reading, I learned that preferential voting and the 'bureaucratic model' of elections are (probably in order of importance) also majoritarian expressions. Which makes sense.

Preferential voting—as much as compulsory voting—ensures majoritarian legitimacy. Page 9:

"Preferential voting is as distinctively Australian as compulsory voting. Both ensure that the governments we elect have the support of the majority of voters."

This is also how politicians thought of it when it was introduced. Page 85:

"The government’s first Electoral Bill included preferential voting for the House of Representatives. It was a modified version of the optional preferential vote already used in Queensland and would, Richard O’Connor told the Senate, ‘bring out in the most certain way possible the choice of the majority of the electorate’.

Page 90:

"Nevertheless, and without Labor’s support, in August 1906 Deakin’s Minister for Home Affairs, Littleton Groom, introduced a Preferential Ballot Bill, which would, he said, ensure that the laws enacted by the parliament would ‘truly reflect the views of the majority of the electors’.

The 'bureaucratic model'—an independent and professional electoral administration—also reflects the majoritarian political culture. Page 183:

"With preferential voting and non-partisan electoral administration, compulsory voting forms a triumvirate protecting our majoritarian faith in democracy and our commitment to peaceful constitutional processes for resolving differences."

(7) Elections exemplify Australia's bureaucratic culture.

After Federation, the Commonwealth adopted the organisational model that William Boothby had pioneered in South Australia. It entailed:

"a Chief Electoral Officer for the Commonwealth, a Commonwealth electoral officer for each state and a district returning officer for each division. All would be permanent, salaried public servants with their duties defined by law and set out in detailed printed instructions. This independent electoral administration charged with the impartial management of elections would be the Electoral Branch, located in the Department of Home Affairs. Extra help would be needed at election times, which would for the most part come from postal officers." (p74)

This model—which, apart from refinements, has remained in place since federation—is called the 'bureaucratic model':

"The political scientist Colin Hughes calls this system, established at the outset of federation, ‘the bureaucratic model’, evidence of what his fellow political scientist Alan Davies called Australia’s ‘talent for bureaucracy’. Not only does it impose order and regularity, but more importantly it sought to keep the management of elections out of the reach of politicians." (p74)

(8) How inevitable were compulsory and preferential voting?

On the one hand, our majoritarian political culture makes them seem natural.

But the other, equally strong theme of the book is that choices about voting systems were often driven by political calculations about what would maximise electoral success for the party considering them.

For example:

"In May 1906, with an election due at the end of the year, Deakin sounded out Chris Watson. Compulsory preferential voting, he wrote to him, would prevent our candidates doing so much harm to each other—and one of them would win in several Reidite Free Trade constituencies. ‘It would be a great safety valve for us both? What do you think?’ Again Labor was not interested." (pages 89-90)

Federal Labor didn't support compulsory voting proposals for many years, because they weren't coupled with compulsory registration. Labor was afraid that to have the former without the latter would cause a swing against Labor.

In the early 20th century, a large portion of Labor's constituents were itinerant workers. They didn't bother to update their addresses, so weren't registered to vote. Compulsory voting without compulsory registration would therefore bias electorates against Labor (or so Labor feared).

Pages 99-100:

"Not only were working-class men less likely to own property, but much of their work was itinerant. Some of these men had no fixed address; others were away from their place of residence for long periods, or moved frequently and didn’t bother to re-register. Labor was only likely to support compulsory voting once compulsory registration removed its doubts about the bias of the rolls."

See also, for example, the early debates on compulsory voting, where decisions about whether or not to adopt measures were driven by "partisan advantage" (page 96).

So how should we think about the inevitability of compulsory and preferential voting?

If their adoption was, variously, delayed or driven by political self-interest, doesn’t that take the legs out from underneath the argument that our political culture made them inevitable? Or is the correct way to think about these two causes as nested: our political culture defines the space of what’s possible, and then politics determines exactly what gets adopted, when, and in what form, within that space?

Judy analyses language used in parliamentary debates. In the debates over compulsory voting, for instance, politicians framed their arguments in majoritarian language. For example:

"Mackey took them in a decidedly authoritarian direction. As it was already illegal to buy and sell votes, it followed that it should also be illegal not to vote at all: ‘The State has a direct interest in seeing that a vote is cast…on public grounds alone, and not for corrupt consideration…just as the State makes rules against the corrupt voter, so it is justified…in making laws against the indifferent voter.’ Notice how easily Mackey talks of the state making laws to compel the vote. This shows how little purchase social-contract and natural-rights theory had on Australians’ common-sense political thinking. Mackey does not see voting as a right belonging to the individual so much as an obligation bestowed by the state." (p97)

But what does this prove? Politicians will always dress their arguments in language that appeals to the prevailing political culture, even if they are driven by cynical calculations.

(9) Judy follows Hugh Collins in arguing that Australia has a 'Benthamite' political culture. But through pages 4-7, the evidence for this is only circumstantial (e.g. based on timing). Do we have any direct evidence that the founders of Australia's political institutions were reading Bentham or other utilitarians?

One explicit link comes on page 22. But it's limited. Henry Chapman was directly influenced by Jeremy Bentham when designing Victoria's first secret ballot for the 1856 election (its first parliament):

"Chapman began with Jeremy Bentham’s suggestion in his 1819 Radical Reform Bill that the voter should arrive at the polling booth empty-handed, rather than bringing his already filled-out voting paper with him, which as likely as not had been provided by one of the candidates. All the materials he needed to vote would be supplied to him, and the government would bear the cost."

Is there any other evidence?

Catherine Spence read John Stuart Mill, which inspired her 'effective voting' (a form of proportional representation). Page 29:

"In 1859 she read a review by John Stuart Mill in Fraser’s Magazine of three recent publications on parliamentary reform. One was by Thomas Hare: ‘A Treatise on the Election of Representatives, Parliamentary and Municipal’. Its ideas electrified her. A lawyer committed to political reform who moved in the same circles as Mill, Hare had devised a system of voting which would give some representation to minorities. It showed Spence ‘how democratic government could be made real, safe and progressive’, and ‘the reform of the electoral system became the foremost object of my life.’"

On page 18, there are some claims about the political dispositions of the mid 19th century migrants to Australia:

"These new arrivals had learned their politics during the 1830s and 1840s. Most were literate; many had participated in the Chartist movements and read the Chartist press; others had read the books, articles and pamphlets of philosophical radicals like Jeremy Bentham and James and John Stuart Mill, arguing that the power and privileges of the aristocracy were unjustifiable and that parliament had to become more representative."

(10) A quick refresher on how preferential voting and proportional representation can overlap.

In a single-member system (e.g., Australia’s House of Representatives), preferential voting is used to elect one winner in each district, which is not proportional. Only the highest-ranked candidate ultimately wins a majority.

In a multi-member system (e.g., the Single Transferable Vote in some legislatures), preferential voting can yield a proportional outcome. Voters rank candidates, but multiple seats are allocated according to vote shares and the transfer of preferences until all seats are filled.

You can have preferential voting in a non-proportional context: that’s Australia’s instant-runoff voting in single-member electorates.

You can also have preferential voting in a proportional context: that’s the Single Transferable Vote (STV), used in some upper houses (including the Australian Senate). There, your ranked preferences help elect several members in proportion to the total support.

(11) In explaining Australia's bureaucratic culture, I'd underestimated the lack of taxation in the colonial era as a factor.

In Judy's account, she highlights this as a second explanation, alongside the influence of Bentham's political philosophy. She draws heavily on John Hirst here.

For the first hundred or so years after British settlement, Australians didn't have to pay much for their own governments, nor were they taxed much—so they lacked the impetus for adopting the rights-based, small-government culture that America embraced.

Pages 7-8:

"What’s more, for the first hundred years or so Australian taxpayers didn’t even have to pay much for the services government provided. The threat of taxation, a major motivator of liberalism’s defence of individual rights and arguments for small government, was largely missing. The British government paid for the early Australian governments. Remembering the American colonies’ revolt over taxation without representation, it decided not to tax the Australian settlers. Britain would gain its economic return instead from increased trade and investment opportunities. Nor did Australia have to pay for its own defence, as this too was provided by the British government. With little taxation, why would people want to limit government expenditure on services that benefited them? ‘So,’ writes the historian John Hirst, ‘the function of government changed in Australia: it was not primarily to keep order within and defeat enemies without; it was a resource which settlers could draw on to make money.’ The paternalism of the Australian state is based on the circumstances of our settlement."

(12) Near-universal manhood suffrage came about in Australia in the 1850s, almost by accident.

Two things contributed to this.

First, the minimum property qualification set sufficiently low. Page 15:

"The New South Wales Legislative Council had recommended that the minimum property qualification be twenty pounds’ rent per annum. This was too high, said Lowe. It would exclude respectable free immigrants yet to establish themselves and should be halved. Otherwise the electorate would be dominated by wealthy ex-convicts and their native-born children. Nothing was more likely to persuade Britain’s rulers than fear of convict influence, and the House of Lords agreed. Ten pounds was the same as the British property qualification, which comfortably excluded most working men. They expected it would also do so in the colonies. But they were badly mistaken."

Second, the gold rush caused inflation expanded franchise above the minimum property qualification. Pages 15-16:

"The second accident was the discovery of gold in Victoria. Rents were already higher in the colonies than in Britain, especially in Sydney and Melbourne, and goldrush inflation soon pushed them higher still."

The result? Page 16:

"By 1856, when the first elections were held for the new Legislative Assembly, 63 per cent of adult men in the settled districts of New South Wales could vote and a whopping 95 per cent in Sydney. In England at the time only around 20 per cent of men could vote."

(13) In Australia, early near-universal manhood suffrage incentivised the adoption of secret ballots—in an inverse of the British dynamic (see pages 18-19).

In Britain, the aristocracy pushed to keep voting open so as to control the choices of their enfranchised property tenants, who risked retaliation if they voted against the landlord's candidate.

In Australia, the opposite held: faced with a wave of working class voters, conservatives argued that secrecy was needed to protect them from the intimidation of the radical masses.

(14) Australia didn't quite invent the concept of the secret ballot. But it introduced practical innovations to ensure actual secrecy. (p23)

These debuted in South Australia (1856) and were the brainchildren of Henry Chapman. Pages 22-23:

The novel part of Chapman’s plan was not the secrecy itself but the means by which the secrecy was achieved: the government-provided ballot paper. Traditionally governments would issue the writs, but otherwise not be involved in running elections. It was left to the candidates and their committees or parties, or to the voters themselves, to organise ballot papers. All the polling booth needed was a ballot box to put them in. Now the government would oversee the whole operation. The printed ballot papers listed the names of the candidates, and voters crossed out those they rejected. This made it easy for those who had difficulty writing. Those who couldn’t read could vote if someone told them which lines to strike out—‘every line after the first’, for example, or ‘all except second from the bottom’. They could also ask for assistance, as could the blind.

But Chapman’s plan required further innovation. How and where was the ballot paper to be filled in? What would prevent the watchful eyes of the candidates’ electoral agents from checking how people voted? Chapman’s proposal was this. The voter would pick up a ballot from the polling clerk, who would mark his name off the roll and sign the back of his ballot to prevent fraud. The voter would then pass into an inner room where he would vote in private, with pen, ink and blotting paper provided. He would then return to the polling clerk and put his folded ballot in the box."

Page 23:

"The invention of the voting stalls, says John Hirst, was just as crucial to the success of the scheme as the ballot paper. Together, these practical measures made secret voting a workable reality. It is often said that Australia invented the secret ballot. This is somewhat misleading, as it was already in place elsewhere. What Australia pioneered were new and more efficient means to implement it."

(15) Three of Australia's great nineteenth century electoral innovators—William Boothby, Catherine Spence, Mary Lee—emerged in South Australia. Coincidence?

Judy refers to South Australia as "the cradle of our earliest electoral innovations". (p137)

South Australia was created by an Act of British Parliament, as a colony of free settlers. (p27)

It's probably no mistake that a disproportionate number of our early electoral innovators emerged there, as utopian, entrepreneurial families would self-select into the new society.

The Spences moved to South Australia in 1839, when she was Catherine Spence was 14. (p28).

William Boothby arrived in Adelaide in 1853, when he was 24. (p33)

(16) When voting on the referendum for the federal constitution, South Australia was the only state with women's suffrage. It needed assurance that its women wouldn't be excluded, so s41 was drafted. (p42-43)

(17) Despite being a small and conservative colony at the time, Western Australia was the second colony to adopt women's suffrage, which it did in 1899.

The reason for this was cynical/political. The 1890s gold rush meant that the south-west corner of WA was filling up with radical voters from other states. The conservatives in Perth wanted to offset this. So they gave women the vote to rebalance the electorates. (Women were underrepresented in the gold fields.) (See pages 41-42)

(18) In the colonial parliaments, upper houses were given more restricted franchise because they were designed to be conservative, to protect the status quo from impulses of popular feeling (pages 46-47).

As John Hirst observed: during the nineteenth century "An upper house elected on a democratic franchise was almost a contradiction in terms." (p47)

(19) Turnout in Australia's first federal election, in 1901, averaged about 60% across the states. (p50)

(20) The first decade of Australian politics after federation was chaotic.

Page 51:

"The next ten years were unstable and sometimes chaotic, as the three parties vied for control. There were seven changes of prime minister until Labor won the election of 1910 and became Australia’s first majority government."

(21) Aboriginal people nearly got the vote after Federation.

Pages 56 - 72 provide a riveting and tragic account of the parliamentary debates on Aboriginal disenfranchisement.

Edmund Barton and O'Conner had proposed uniform adult franchise.

The Franchise Act of 1902 determined who could vote.

The franchise bill was initially framed expansively by Barton's government—all adult persons "who are inhabitants of Australia and have resided therein for six months continuously" would have the vote. (p53)

What about the Constitution?

Section 41, read expansively, would give all Aborigines the vote. (p59)

Section 127 was intended merely to exclude them from electoral calculations so that states like Queensland and WA with large (and often nomadic) indigenous populations did not receive more seats than their white population warranted. (p59)

When s127 was being discussed at the conventions, Deakin and Richard O'Connor had assured John Cockburn that it would have no effect on the voting rights of Aborigines already on the roll.

On the second day of debating the 1902 Franchise Act in the Senate, WA Senator Alexander Matheson moved the crucial amendment excluding Aborigines. (p60)

Even Henry Higgins—of Harvester judgment fame—wanted Aborigines excluded. Pages 63-64:

"The radical liberal lawyer Henry Bourne Higgins then moved to have ‘Australia’ reinserted.

'It is utterly inappropriate to grant the franchise to the aborigines, or ask them to exercise an intelligent vote. In as much as all that we are constrained to do is to keep alive existing electoral rights in pursuance of section 41 of the Constitution…I do not think that there is any constitutional obligation on the committee to provide for a uniform franchise for the aborigines.'

For Higgins, the ideal voter was a well-informed, independent citizen living in a civilised community. This ideal later informed his famous Harvester Judgment, which he delivered in 1907 as president of the Commonwealth Court of Conciliation and Arbitration. He based his determination of a fair and reasonable wage on ‘the normal needs of the average employee regarded as a human being living in a civilized community’. Intelligence, independence, civilisation: these were what qualified a person to vote, and Higgins could see none of these qualities in Aborigines, though it is doubtful that he knew any."

In the end, Aborigines were decisively excluded. Page 65:

"When Higgins’s amendment restoring the original wording and excluding Aborigines was put to the vote, it wasn’t even close: twenty-seven Ayes to five Noes."

They didn't start to receive voting rights again until WWII, where those who'd served were temporarily franchised.

In 1962, all Aborigines were franchised. And in 1983, they became subject to the same voting laws as other Australians (namely, both enrolment and voting were made compulsory for them). (p72)

(22) Aboriginal people probably could have got franchise about 40 years earlier than they actually did, but no one bothered to mount the High Court challenge that would have unlocked it.

Pages 69-70:

"in order to prevent Mitta Bullosh becoming a precedent for a broad interpretation of section 41, which would have extended the franchise to Aborigines and to many other excluded people in New South Wales, Victoria and South Australia, the government passed a special law to give voting rights to Indians. The 2,300 Indians in Australia were appeased, and the narrow interpretation of section 41 continued to guide the decisions of electoral officers. Had an Aborigine on one of the state electoral rolls mounted a similar challenge, Aborigines might have gained the federal franchise forty years earlier than actually happened, but none did. Nor were there any progressive lawyers offering to support them."

(23) The 1902 Electoral Act provided for postal voting, and also allowed electors to vote at any state polling booth regardless of where they lived (p81)—this too reflects Australia's political culture.

Page 83:

"Sometimes Australia’s commitment to flexible voting arrangements is explained by our compulsory voting. If the government forces you to vote, it has to make voting easily available. But in fact this flexibility was already there in the Commonwealth’s 1902 Electoral Act, and is the result of the same deep streams in Australia’s political culture: our untroubled reliance on the state to organise things for us, our commitment to majoritarian democracy, and Labor’s sensitivity to any voting regulation that carried the shadow of a property qualification."

(24) Labor rise as a political force was rapid—and shows how quickly a new party can go from zero to one.

Pages 88-89:

"At the first federal election in 1901, Labor polled only 18.7 per cent of the House of Representatives vote. It won fourteen seats in the House and was the smallest party after the Liberal Protectionists, which formed government with thirty-one seats, and the Free Traders, with twenty-eight. But Labor’s electoral support was rising rapidly. At the 1903 election it polled 30.67 per cent of the vote and won twenty-three seats, taking five from the Liberal Protectionists, three from the Free Traders and one from an independent."

By the 1910 election—within about two decades of its emergence—it "won 49.97 per cent of the vote and formed Australia’s first majority federal government." (p91)

(25) If preferential voting was introduced earlier, Labor might have been stunted as a political force in Australia.

Page 90:

"It is not fanciful to argue that if the first federal government had succeeded in introducing preferential voting for the House of Representatives in either 1902 or 1906, the course of Australia’s political history might well have been different. Labor’s electoral rise might have been slowed, and the Liberal Protectionists might have consolidated their position as a centrist governing party."

(26) Voter compulsion was administratively efficient.

Pages 105-106:

"Labor also made voter registration compulsory. This policy innovation was based on the advice of the Chief Electoral Officer, Ryton Campbell Oldham, another of the unknown heroes to whom we owe our democratic electoral system. Oldham was a strong advocate of compulsion in electoral matters, chiefly on grounds of administrative efficiency. He had a bureaucrat’s pride in his systems; he and his officers were building a card index ‘to secure a clean and continuously effective roll which will, at all times, be free from duplications’. Under the current system of voluntary enrolment, he argued, there were too many errors and omissions ‘due to public neglect, carelessness, and apathy’, with many people believing that ‘it is the duty of the electoral administration to follow them from place to place, and relieve them of the obligation of taking action in the preservation of their electoral rights.’ Australia’s exceptionally large migratory population, with at least 20 per cent of city electors changing address each year, placed an unreasonable burden on government officers responsible for the roll, he said. ‘It should be the duty of all qualified persons to enrol within a (reasonable) prescribed period, and to transfer or change their enrolment when they remove from place to place.’"

What would James C. Scott say about this?

(27) Seats that go to preferences have been trending up.

Page 140:

"Since the 1990s the number of seats decided by preferences has increased markedly. Thirty-one seats went to preferences in 1983, sixty-three in 1993, eighty-seven in 2001, and in 2016 an astonishing 102 out of 150 seats. These were no longer the traditional two-horse race between Labor and the Coalition. And where preferences once helped the Coalition win seats, they now more often help Labor."

(28) When it was first introduced, the penalty for not voting was about 8x higher.

Page 3:

"When it was first introduced, the penalty for not voting was high: two pounds, or $160 in today’s money.8 In 2017 the fine for not voting in a federal election without adequate reason was only $20, scarcely enough to compel a high turnout."

(29) Women voters tended to favour the Liberals until the 1970s.

Page 105:

"Robert Menzies would later make much of Liberals’ support for the home in his 1942 radio broadcast to the Forgotten People. Until the Whitlam government embraced second-wave feminism thirty years later, women voters favoured the Liberals."

(30) Queensland pioneered compulsory voting in the English-speaking world.

The English-speaking world's first compulsory-voting election: 1915 in Queensland. Page 118:

"The election on 22 May 1915 was the first in the English-speaking world at which voting was compulsory for everyone on the electoral roll. The turnout was 88.14 per cent, a notable increase on the 70 per cent which had voted in 1912, and the female turnout was 90.09 per cent."