Hugh White’s Notes on Australia’s Strategic Circumstances (1993)

By HUGH WHITE

Preface by JOSEPH WALKER

Preface

Sydney, November 2025

Joseph Walker

The note below was written by Australian strategic analyst Hugh White. Hugh mentioned the note in our podcast conversation. I asked if I could publish it, and he generously agreed.

It was written in January 1993, originally for an audience of one: Hugh himself.

From 1985 to 1991, Hugh served as a defence and foreign policy adviser, first to Defence Minister Kim Beazley and then to Prime Minister Bob Hawke. After Paul Keating wrested the prime ministership from Hawke, Hugh moved to the Office of National Assessments, where he spent 1992 as head of the Strategic Analysis Branch. With his phone ringing a lot less than it had in the PM’s office, he finally had time to sit and reflect on the emerging post-Cold War order.

In early 1993, after a year of rumination, Hugh was pitched into the Department of Defence, where he aspired to help reshape Australia’s strategic and defence policies. (He would be appointed Deputy Secretary for Strategy and Intelligence in 1995 and become the primary author of the Defence White Paper of 2000.)

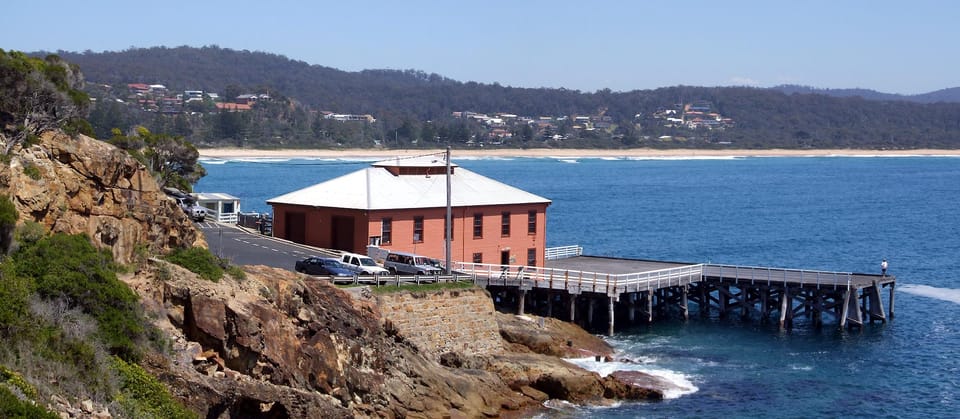

The summer of 1992-93 provided an interregnum between ONA and Defence. On a family holiday to Tathra on the south coast of New South Wales, Hugh found a chance to crystallise ideas that had been brewing for years and came to a boil in 1992. As Hugh told me by email, he wrote what he came to call the ‘Tathra note’ in a few quiet days between tending to his family members, all of whom were bedridden with a stomach bug.

He churned out more than 13,000 words — until family duties interrupted again or the holiday ended. The note breaks off in the middle of the argument.

The Tathra note was, Hugh tells me, the last substantial thing he ever wrote by hand.

It also represents his first substantial attempt at wrestling with the strategic implications of China’s rise — the theme for which he would become best known and which would define his published work in a string of books and essays beginning in 2010 and still in motion as of 2025.

With Hugh’s kind permission, I was keen to publish the note for two reasons.

First, it has plain historical value. It’s one of the earliest examples of a senior Australian policymaker contending with the grand strategic question of the rise of China and clarifying his thinking through that time-honoured exercise of writing it down. It also seems to be one of the first written instances of a hierarchy of Australian strategic interests modelled on Britain’s — a formulation that would reappear in Hugh's work in the Department of Defence in the 1990s, culminating with the 2000 White Paper (sometimes dubbed the ‘White White Paper’).

Second, it’s a case study in the art of prediction. Reading the note, we find Hugh peering at the 21st century through a fog of radical uncertainty. He makes predictions (either implicitly or explicitly) that proved prescient, and one or two that did not. As he tells me by email, “rereading [the note] recently for the first time I was struck by how wrong I was about Japan, in ways that seem rather interesting now.” (In the late ’80s and early ’90s, many analysts foresaw Japan becoming the primary challenger to America in East Asia and the Western Pacific.) Hugh also tells me: “On America, I was wrong for a couple of decades before I became right!” (American primacy in the Western Pacific didn’t begin to fray until the 2010s.)

Conversely, his confidence in China’s trajectory was on the money, and his emphasis on it was prudent. China’s rise to hegemony seems almost natural now, but it was far from obvious in 1993: China’s GDP (in purchasing power parity terms) was only about 20% the size of America’s in 1992. Hugh tells me that it was Ross Garnaut who convinced him that China was likely to follow the other Asian Tigers in sustaining real GDP growth of 10% per year for a couple of decades. Such a growth regime would change everything, because in contrast to Japan, whose population then was less than half the size of America’s, China’s population was more than quadruple that of the US.

It was this basic insight that motivated the Tathra note.

With that, over to a 39-year-old Hugh White, at a kitchen table somewhere on the NSW south coast.

Notes on Australia's Strategic Circumstances

Tathra, January 1993

Hugh White

During the first century of European settlement in Australia, the colonists’ overwhelming strategic concern was to secure Australia as a British possession from what they feared to be the predatory attentions of other European powers. We looked to Britain, and especially to the Royal Navy, to do that. Colonial leaders stretched their fledgling feathers as statesmen by urging Whitehall to keep other European powers away from Australia, and keep as many as possible of the ships of the Royal Navy on the Australia station.

At the end of that first century, our strategic perceptions underwent a quick and important change. Soon after Federation, Australians started worrying less about threats from the other European colonial powers in the Pacific, and began worrying more about threats from Asian powers — in particular, of course, Japan. Japan's destruction of the Russian fleet at the Battle of Tsushima in May 1905 marks the decisive break between the strategic preoccupations of our first and second centuries. Alfred Deakin, then Prime Minister, and the best strategist ever to hold high political office in Australia, saw it immediately. An Asian nation had defeated the navy of a European Great Power. At the same time, the European powers including Britain were turning their attention away from colonial competition in distant parts of the world to concentrate on the looming confrontation at home in Europe which has lasted in different forms until the fall of the Berlin Wall: the keel of the Dreadnought, designed as the decisive response to the German naval threat, was laid within a few months of the battle of Tsushima.

Since then, throughout this century, during two world wars and several smaller ones, the strategic policy of Australian governments has been primarily aimed at securing the help of powers outside Asia to help defend Australia from Asian threats. And from the first they looked to America as well as Britain. By 1905 Britain's treaty with Japan showed that Whitehall was already uncertain that the Empire's strategic interests in Asia could be sustained against Japan. So Deakin started to look to America as well, inviting Teddy Roosevelt's Great White Fleet to visit in 1909.

We are now on the threshold of another great change in our strategic affairs, the biggest since the Battle of Tsushima announced the emergence of a Pacific strategic system separate from the European one. During the next century, our third century, Australians will continue to focus, as we have in the present century, on threats to our security from Asian powers. But we will no longer look to powers outside Asia — to our "Anglo-Saxon kin" in Britain and America — to protect us from those Asian threats, as we have during our second century and indeed as we looked to Britain to protect us from other Europeans in our first century. In our third century, we will stand alone, or look for allies in Asia itself. That is what we mean when we say that we must become strategically enmeshed in Asia.

The reason for this fundamental change in our strategic situation is simple enough. Throughout the two centuries of European settlement in Australia, and indeed for several centuries before that, the strategic affairs of Asia, especially at sea, have been dominated by outside Western powers. That era, the era of Western dominance, is now drawing to its close. Such great events must themselves have great causes: this one has two. The lesser of these is the end of the Cold War.

1. The end of the Cold War

In the early 1950s, the great Indian historian of Asia's colonial era, K.M. Panikkar, declared the end of 450 years of Western Dominance in Asia with the collapse of the European empires after the Pacific Wars. He was wrong. It has lasted for another fifty years, during which two outside powers — superpowers both "Western" in Panikkar’s sense — contended for strategic dominance in Asia as part of the world-wide competition of the Cold War. That phase — so momentous in the history of our century, though perhaps little more than an epilogue to the story which began with Vasco da Gama off the coast of India in 1498 — has come to a bewilderingly abrupt end with the collapse of the Soviet Union just over a year ago.

Russia

The collapse of the Soviet Union is a huge event which will reverberate for decades. Even its most direct effects will take some years to become clear. The normal failing of humankind is to overestimate the effects of small events, and underestimate the effects of large ones. Most directly, the collapse of the Soviet Union marks the strategic decline in Asia of the last European colonial power. Russia retains its Asian territories. But the collapse of the Soviet political and economic system, the chaos which has been left behind in Russia and on its borders, and the scale of economic and political reconstruction, have transformed Russia's situation in the Far East. Instead of being a springboard for Soviet strategic, economic and political interests in East Asia, the Russian Far East has become instead an isolated and potentially vulnerable backwater. Surrounded by the mighty economies of North East Asia, with its potential wealth inaccessible for lack of infrastructure, the Russian Far East will be developed, if at all, by Asian capital to serve Asian markets: it will in effect be re-colonized by Asia.

Strategically, the Far East is likely to become more of a liability than an asset to Moscow requiring disproportionate effort to defend it from increasingly well-armed neighbours. If present trends continue, Russia's Far East will become less one of the players in Asian strategy and more one of the prizes.

Of course, Russia has been in trouble in the Far East before — in its war with Japan in 1905, and during the civil war of 1919-21, when Japan occupied a lot of Russian territory. Whether Russia can avoid that fate this time, and bounce back again to take its place among Asia's great powers, depends on the course of the revolution now underway in Russia. Its best hope is probably to copy the blend of authoritarian politics and relatively liberal economics which is now called the Asian model. But Russia is not Asian enough to give one much confidence that the Asian model would work there. Even if Russia does quite quickly create new political and economic systems that work, it would still be many years before Russia returned to the world stage. And when that happened, it would be as a great power, not a superpower. As a great power, Russia's attention will be directed westward, to the difficult strategic relationship with the Ukraine and the economic opportunities of Europe, and southward, where the problems and conflicts of the Middle East have suddenly marched to Russia's borders. The Far East will come a poor and distant third.

Moreover, when Russia returns as a great power, it will be above all a land power. The Soviet Union built a huge Navy because as a superpower it sought global influence: as a great power Russia's terrestrial needs will leave little money and little reason to re-build a major navy. Without a navy, Russia's strategic opportunities in Asia are hemmed in by China; and Asia remains, as it was when the Europeans first dominated it with square-rigged ships and brass cannon, a predominantly maritime strategic theatre. Without a big navy, Russia will not be a great power in Asia whatever it might be in Europe or the Middle East. And even if Russia retains a big strategic nuclear arsenal, it will be hard to use as an effective instrument of national policy without huge conventional forces to back it up.

But the eclipse of Russia as a Great Power in Asia is not the only way in which the collapse of the Soviet Union marks the end of Western domination of Asia's strategic affairs. A second effect, less distinct and less certain, is nevertheless potentially more powerful.

America

For over fifty years, since the tide of the Pacific War turned at the Battle of Midway in June 1942, America has been the dominant military power in the Western Pacific. Since Japan was defeated, America has maintained that dominant position primarily, indeed overwhelmingly, to prevent communist and especially Soviet domination of the region. Now that danger has gone. As a result, America's strategic role in the Western Pacific will shrink. It would defy the law of gravity for America to sustain such a mighty effort when the main reason has passed. There have been changes in the US strategic position in Asia before, and questions about America's strategic commitments in the region were asked after the Guam Doctrine, just as they are being asked today. But this is different. It is quite unclear how far or how fast the rundown will go, but we must try to establish at least the range of possible outcomes, because the US role is the key variable in Asia's strategic equation at the end of the twentieth century. We can start by dismissing the extreme positions between which popular and even professional opinions swing. On the one hand, as I have said, America will not sustain indefinitely a strategic position in Asia designed to contain the Soviet superpower after the Soviet Union's collapse. On the other hand, America has not and will not respond to the end of the Cold War in Asia or elsewhere by simply relapsing to the isolationist strategic position that was traditional to the United States before it became a superpower. After fifty years of successful global leadership, active engagement around the world is normal rather than aberrant American strategic policy. Americans have got used to being a superpower.

But saying that America will not relapse into isolation is not after all saying very much. American policy makers and opinion formers are convinced that America has a role to play, but they are profoundly uncertain what that role should be. America is now a bit like Britain was after the Second World War: to paraphrase the unkind words of Dean Acheson, America has won the Cold War and lost a role. The confrontation and containment of the Soviet Union was not just a policy for successive US administrations: it was a mission which helped Americans define themselves and their country. As a mission it was clear, simple and immediate; it did not take much imagination for every American to see what was at stake. And perhaps most important, it was a mission which could be defined and explained in terms of ideals rather than interests. Throughout its history America's foreign policy and especially strategic policy has aimed to promote its ideals rather than its interests. Americans have (almost — except Teddy Roosevelt) always thought it immoral to go to war for an interest, no matter how vital — especially an interest outside the Western Hemisphere. Going to war for an ideal, on the other hand, comes quite naturally to them.

American leaders have never succeeded in mobilising national opinion in support of a sustained strategic commitment outside the Western Hemisphere on behalf of American strategic interests unsupported by a clear and compelling context of ideals. Perhaps that's because until 1941 Americans did not consistently believe that they had strategic interests outside the Western Hemisphere that were worth fighting about.

So America's leaders now face the task of identifying and explaining to their people what America's strategic interests are in the post Cold War world. They have not so far made a very promising start. The only notable attempts by American leaders to define America's strategic interests without resort to ideology was the Pentagon's draft Defence Policy Guidance Paper, leaked in February 1992. It made a sensible start at the problem by saying that America's main strategic interest is to prevent the emergence of any new superpower which could renew the Soviet challenge to America's security, and concluded that America would be more secure if neither Japan nor Germany became dominant in their respective regions. It's hard to argue with that, but American public opinion is not ready for such frankness, and American leaders are not ready to educate them on it. Instead the issue has been avoided by defining America's interests very generally in terms of the spread of democratic values, human rights, and US trade interests. These are fragile foundations for the strategic policy of a global power.

Of course, Americans keep being told the world is a dangerous place, and they have been given plenty of examples: Kuwait, Yugoslavia, Somalia. But these have provided unconvincing instances from which to generalise a new US strategic position. Each of them is proving resistant to solution by the application of armed force — even in the Gulf where Bush allowed Saddam to become the problem, rather than the invasion of Kuwait, and so made a solid victory appear an empty failure. And all of them make Americans worry whether their new strategic role is going to be simply that of the thankless policeman and social worker of the world's international slums. Each new crisis makes Americans less certain what their new role is, and more anxious to see it both more clearly defined and more clearly limited.

And of course Americans wonder if they can afford to maintain Cold War-scale defence forces now that the Soviet threat has passed. It may be true that America's economy would benefit if its government spent less on defence, at least in the longer term. It is certainly true that Americans will take a lot of persuading that they cannot spend less on defence now that they've beaten the Soviets. So there will indeed be sharp and sustained cuts in defence spending. But it is not true that America can no longer afford to sustain a globally-dominant strategic position, if by that we mean that continued defence spending at the levels necessary would permanently undermine America's economic health.

For many years to come, America will have the largest economy, the most productive workforce and the most dynamic and innovative technology in the world. And even the most expansive definition of America's global strategic role in coming decades could still be implemented with much smaller forces than America has sustained in recent years. So if, as I expect, America takes a smaller part in the world over the next fifty years than it has during the Cold War, the cause will not be lack of money, but lack of will.

The size of America's armed forces at the end of this decade will be determined by the strategic role which American leaders can convince the public that America needs to adopt. So far, America's leaders have done little to define a role or sell it to their countrymen. President Clinton, soon after his election in November 1992, gave a revealing clue: he said America would continue to be the world's strongest military power. That's got a good ring to it, but it's a very modest objective for the world's only superpower. If President Clinton is prepared to allow America's forces to shrink to the point that they are just bigger than the next fellow's, he can cut defence spending much further than anyone has yet hinted. And if he sticks to the views of Nunn and Aspin which he endorsed during the '92 campaign, he will have a sound defence-policy basis to make those cuts. Nunn and Aspin say that US defence capabilities should be tailored to meet specific threats, rather than to fill pre-defined roles. That's a good idea if you have a clearly-defined and well-identified threat to address. But as we in Australia know from the experience of the past twenty years, defence planning is different when you do not have a threat. We find that if you try to apply a threat-based defence policy when you can't clearly identify threats, you end up with defence forces which are very small indeed.

These uncertainties about America's strategic role and military capability affect most strongly the permanent deployment of US forces overseas. During the Cold War, there was no doubt what US forces in Europe, North East Asia and elsewhere were there to do. Their commanders could state quite clearly who they were there to fight, and under what circumstances they would do so. That certainty has now gone. It is common to speak of military deployments as having a diplomatic or political purpose, but those purposes can only be derived from their capacity to fulfil a military role. Without a clear military role, armed forces deployed abroad stop being a symbol or token of commitment. If they are not clearly committed to the security interests of the countries they are based in, they will soon start being seen as a symbol of disengagement rather than of engagement. They will become unwelcome abroad, and their bills will become unwelcome at home. So if America is to maintain its overseas deployments, it must define the role of these forces in specific military terms: it must be prepared to say when they will fight. That means it must enter into specific, new commitments to defend host nations’ interests in the post Cold War world. This is the cutting edge of the issue of America's world role. Americans must be prepared to make specific commitments to the security of other nations if they are to continue to base forces abroad: and if they don't continue to base forces abroad, their role as a world power will sharply diminish.

So much for America's commitment to a global role. What does it mean for the future of its strategic role in Asia? The key to that role remains, as always, in Northeast Asia, where Asia's wealth, people, and military power are concentrated. The end of America's quasi-colonial link with the Philippines is a neat symbol of the end of the Western era in Asia. But the end of a century of American deployments in the Philippines will not erode America's strategic position in Asia significantly, as long as its position in Northeast Asia can be sustained.

America's strategic dominance in Asia depends on the permanent deployment of US forces in the region. America will always be able to deploy large forces into the region, and will be influential as a result, but without permanent deployments of substantial forces, with clearly defined roles, it cannot dominate an area as rich and big as Asia. It's not like the Middle East.

US forces will most likely have withdrawn from Korea at the end of the century. By then, Korea will either be re-unified, in which case the rationale for basing US forces on the peninsula will have evaporated; or it will consist of two more or less compatible states, the North having staved off collapse and re-unification by economic reform at home and enough diplomatic and military accommodation abroad to allow substantial foreign investment, especially from Japan, to pull it back from the economic and political brink. It's just possible that North Korea may hold on as it is; angry, isolated, unreformed but undefeated. Even then, it will have fallen so far behind South Korea as no longer to pose a military threat to South Korea beyond Seoul's ability to contain. And of course the end of the Cold War deprives the Korean Peninsula of its special status as the crux of East-West confrontation in Asia. Whatever happens, it's hard to see a place for US forces.

America and Japan

Once US forces are out of Korea, America's strategic position in North East Asia, and hence in Asia as a whole, will depend on its position in Japan. America's position in Japan is important to all of Asia, because by dominating Japan, America contains what would otherwise be the greatest, or one of the two greatest, strategic powers in Asia: by dominating Japan, it dominates Asia. (Dominating is the right word: Japan's consent to the relationship does not make it any the less one of dominance. The Japanese, being hierarchical, accept that as long as the hierarchical relationship is clear; they become uncomfortable when the hierarchy becomes ambiguous). That makes the US position in Asia inherently less secure than in Europe; because in Asia it depends on a single bilateral relationship, unlike in Europe where it has a broad alliance in NATO.

The security relationship between Japan and America was of course built on the foundation of the Cold War. Japan's fear of Soviet attack, and America's fear that the Soviets would invade or intimidate Japan unless it was protected, gave them the deepest identity of fundamental strategic interest imaginable. On these foundations they built one of the closest strategic relationships between independent countries in history. Over the decades many tensions and disputes have washed at these foundations without moving them much. Whether the relationship can last indefinitely now the Russian threat is over depends on the interests and the attitudes and the capabilities of the two sides.

Neither side wants the relationship to collapse. In both Washington and Tokyo there are those who argue that the relationship has outlived its usefulness. But on both sides of the Pacific governments backed by a healthy preponderance of influential opinion want to see the relationship endure. In Japan the political class continue to find it hard to imagine a strategic policy for Japan without the US security relationship, and they strongly believe that whatever happens Japan would be worse off without it. These sentiments give some reassurance that the relationship will not collapse quickly. But they give no guarantee that the relationship can evolve to fit new strategic circumstances in ways which meet the interests and attitudes of both parties.

The most obvious solvent of the relationship are the trade disputes which are inevitable between the world's two largest economies. Trade issues have dominated and disrupted bilateral relations in recent years, but they have been mostly insulated from the strategic relationships. The trade disputes will remain; but they will be less well-insulated from strategic affairs than they were during the Cold War, when the primacy of their shared strategic interests over divergent trade interests could not be questioned on either side of the Pacific. Now that strategic interests are more complex and less stark, it will be easier for strategic relationships to be affected directly by trade problems. That will worry Japan much more than it will worry America.

But trade issues are probably not the most serious of the obstacles to sustaining the US-Japan security relationship. They have important and growing differences over political and strategic issues which will strain the relationship more directly than trade concerns. The political problems are partly caused by America's expectations of Japan. For some years American policy towards Japan has been awkwardly ambivalent: it has urged Japan to take a more active role in the world, as it did for example during the Gulf War, but has been sharply critical when Japan has differed even slightly from America on international issues. That ambivalence in American expectations is unsustainable: if Japan is to be active it must be independent. America can't expect the second most powerful nation in the world to be its messenger boy.

The same ambivalence is clear in the issue of burden sharing. There is no doubt that American conceptions of the future of the relationship include a Japan which is both more politically active and also carrying a bigger share of the military burden, but equally remaining amenable to American decision-making. In this, as in America's attitude to international security cooperation through the UN in general, Americans hope or expect that America's leadership will continue when its preponderance of armed strength has diminished. That's based on an assumption that other countries accept America's leadership in deference to its values rather than to its power; its moral strength rather than its military strength. America is a great and good country, but it has dominated Asia not by goodness but by strength. If Japan contributes more, it will decide more; America will resent that, and Japan will resent America's resentment.

Indeed at the heart of American security policy towards Japan is a vicious circle of contradicting attitudes about Japan's own military power. If Japan spends too little on defence, it is bitterly resented for taking a free ride at America's expense. If it spends too much, it is suspected of resurgent militarism and of challenging the US. As America's own military power falls, the gap between the horns of this dilemma narrows; indeed in many influential minds in Washington the gap is closed completely: Japan can do nothing right.

Important differences are already emerging between America and Japan over strategic issues in Asia. Japan worries that America is rushing too fast to build a close relationship with Russia, which now appears more threatening to Tokyo than it does to Washington; Japan mistrusts America's emphasis on democracy and human rights issues, especially in China; and it has resented American pressure to keep out of Vietnam in recent years. It was inevitable that the strategic outlook of the former Cold War allies would diverge once the Cold War was over, but it is instructive that they have diverged so quickly and on such important issues to Japan and to Asia.

Finally, and most fundamentally, there are grave difficulties in explaining the rationale of the security relationship to voters on either side of the Pacific in anything more detailed than the most inane generalities now the Soviet threat has gone. The facts are simple enough: the US security relationship prevents Japan from developing its own armed forces, which prevent it from threatening other countries in Asia. But how can you tell the Japanese people that they must continue to pay billions a year to support American forces in Japan, and continue to accept the inferior political status that this dependence on the US imposes, in order to protect the rest of Asia from Japan? That is an affront to 40 years of Japanese pacifism, and it's an affront to Japan's growing sense of its own legitimacy and status in the world, reflected in its determined bid for a permanent seat on the UN Security Council.

It's not much easier on the other side of the Pacific. Although it's cheaper to keep the 7th Fleet in Japan than it would be to keep it in America, it would be cheaper still to scrap it. The security commitment to Japan is an expensive burden which needs to be justified to Congress and the voters in clear terms of contemporary post Cold War American interests if it is to be sustained for more than a few more years. The awkward analogies (hubs and spokes, bridges, anchors, balancing wheels) which have passed for an Asian strategic policy in Washington over the past few years will not do the job. Neither will simple invocation of America's economic interests in Asia explain why America must be responsible for defending Japan. After all, American voters will say, the Europeans have huge interests in Asia; why don't they have to defend them? And so does Japan. Most basic of all: what are the US forces in Japan there to do? When would they fight? Are Japan's quarrels necessarily America's? So it's hard to see how, over the long term, the need for the relationship can be explained in Washington.

And in Tokyo, confidence in the durability of the relationship is already fading. Japan's policy elites understand very well how Japan benefits from the relationship, and they will continue to work to sustain it. But on top of all the other difficulties described above, they do not believe that American policy makers and politicians will continue to defend Japan's interests. They are losing faith that America will fight for their interests. Once that faith is gone, it is almost impossible to restore it, and the relationship will not long survive.

A strong and complex security relationship like the US-Japan relationship does not disappear quickly. It will slowly fade, as interests diverge and deployments are cut. But the downward slope is not uniformly gentle: there may be some distinct jolts. And at the bottom there is a big drop. The end for the relationship will come very quickly if and when Japan, fearing nuclear neighbours in China, Russia and even in Korea, loses faith in the American nuclear umbrella protecting Japan from nuclear attack.

For the alliance to survive, Japanese have to keep believing that any potential nuclear attacker would be deterred by the likelihood that America would retaliate even at the risk of attacks on the US in return. That assumption was pretty solid during the Cold War, but it becomes harder to sustain as US and Japanese strategic interests diverge. Would America risk a Chinese nuclear attack on Washington to deter a Chinese attack on Japan — or would they press Japan to make whatever concession China was demanding to resolve the crisis? The best guarantee of US commitment to Japan's nuclear defence is the presence of large US conventional forces in Japan. Even with the 7th Fleet in Japan, America's nuclear commitment to Japan is weaker now than 2 years ago: without the 7th Fleet, that commitment would be very hard to substantiate. There is no reason to assume that Japan would not respond to this in the most obvious way — by developing her own nuclear weapons. The need for a nuclear capability has long been an acceptable if minority element of Japan's defence debate. Five or ten years from now that might not seem such a cataclysm for the NPT already breached in the Middle East and the former Soviet Union as well as North Korea. It would be the end of the US-Japan defence relationship.

To preserve the security relationship with Japan after the Cold War, America would need to rebuild it by providing a clear, compelling and politically palatable rationale, and undertaking new and specific commitments about its willingness to use armed forces in defence of Japan's interests and to maintain the nuclear umbrella over Japan against any nuclear threat. I don't think that can be done in America today.

So the most sensible working assumption for Australian strategic policy makers looking ahead to the next century is that early in the next century, the US will no longer be basing significant forces in Japan; that it will no longer take major responsibility for Japan's security; and that Japan will be taking much more direct steps to look after its own interests in Asia.

Depending on how things go in Korea, it may be that there will be no significant US forces based west of Guam, perhaps even west of Hawaii. America will no longer be an Asian power the way it has been for the past fifty, and indeed for the past one hundred years since it took the Philippines from Spain. Of course it will remain the world's largest military power: and while its forces will be smaller than they are today, they will probably be more deployable. That will give America a lot of influence in Asia, more influence than any other outside power. But it will not give America dominance. The last of the Western powers to dominate Asia will have gone home.

2. Economic growth in Asia

The second great trend which is bringing to an end the era of Western dominance of Asia is equally important as the withdrawal of Western powers, but it will need less examination because it is more or less unquestionable.

Asian states are building economies and political systems which are as strong, as vigorous, as durable and as innovative as any in the world. That has been a long, slow process. It started in Japan over a century ago, but Japan left the rest of Asia behind until, in the past twenty or thirty years, China's overseas offspring, and South Korea, started down the same road. Now they are being followed in turn by China, and perhaps later by India.

China appears set to copy what has become the East Asian model of political and economic development; rapid economic growth based on low-wage manufactured exports, underwriting the maintenance of relatively authoritarian regimes which slowly evolve to meet political aspirations as the economy develops. No one can be sure that the model that has worked so well in Singapore, Taiwan and South Korea will work in China. But strategic planning does not deal in certainties. Asia's strategic planners must take account of the strong possibility that over the next few decades China will emulate the economic and political achievements of expatriate Chinese in Taiwan, Singapore and Hong Kong.

Countries numbered in the billions, with economies growing at 10% a year for decades on end, soon acquire the strategic potential to challenge any outside power for hegemony in its own region. China, Japan and India will not become superpowers in the old sense, seeking influence and deploying forces all over the globe; but they will, if they fulfil their present promise, become capable of challenging anyone in their own front yards. For the first time since da Gama brought brass cannon to India, outsiders may be outgunned in Asia.

The coincidence of these two trends is not entirely accidental; common causes can be found in the decline and collapse of the Soviet Union, which has not only brought the Cold War to a final conclusion, but has also exploded communism as an economic doctrine, opening the way for the market-based economic policies which are allowing Asian economies to take off.

3. What will Asia be like?

The end of Western strategic dominance in Asia will make it a very different place. It will not necessarily make it much more dangerous, but it will be rather more complex and fluid. The region is in good shape to meet these challenges. Economically it is prosperous, sophisticated and well-integrated. Politically there are suspicions, but few enmities between states. Good forums for cooperation and conflict resolution, like APEC and ASEAN, are being developed. Some important progress has been made in building on these forums a framework for security consultation. Much of that has focused on what is called a broad, inclusive definition of security, which includes health, customs, environmental, law and order and economic issues as well as the more conventional strategic and military security issues. This inclusive definition is diplomatically useful in allowing discussions and cooperation to begin in less sensitive security areas, and it reflects the important truth that there are many important influences in a nation's well-being other than its military security. But it also conceals an important truth: that war between states can be the most terrible type of calamity and it is the only one that arises between states as a direct result of their international conduct. So it does deserve special and

pre-eminent attention in international affairs.

The end of Western dominance in Asia marks a new chapter in the strategic history of Asia as a whole; many Asian nations which became independent only after World War II have never conducted their international affairs outside the framework of the Cold War. They view the prospect with anxiety about how the region's great powers will behave when they are no longer constrained by the Soviet threat and the US presence. In South East Asia, for example, they worry that Japan will revert to the military policies of fifty years ago; and they worry that China will revive hegemonistic presumptions dating back many centuries.

These possibilities must also concern us in Australia. It cannot be ruled out that the reduction in America's strategic role in Asia will allow and encourage one or other of the great powers to try to dominate Asia themselves. But I think that is a most unlikely outcome. Take Japan first.

Strategically, Japan is a status quo power: its objectives are essentially conservative. It wants to preserve as much as possible the circumstances which have allowed it to prosper so well since the end of the Pacific War. But its conservative outlook is troubled by two anxieties; pessimism about the future of the US security relationship, and unease about the strategic objectives of its neighbours in North East Asia — China, Russia and Korea. As a result, Japan will develop — indeed is already developing — a more outward-looking strategic posture: its defence forces will continue to grow, and it will slowly develop a bigger independent security role in the Western Pacific. And while there will be nothing in this of a return to militarism, it will reflect not just Japan's anxiety to preserve the status quo as much as possible as the US runs down: it will also reflect political ambitions to play a larger role in regional and world affairs commensurate with its power and status as the world's second economy.

Japan's political ambitions are powerful and [as far as they go] legitimate. They are shown most clearly in Japan's open and active campaign to become a permanent member of the UN Security Council. Japan decided to contribute to UN peacekeeping operations because the Gulf War showed that even huge contributions to the cost of UN operations counted for almost nothing in the international community: Japan can only achieve the political position it seeks by sending forces abroad. But Japan's political ambitions do not make it strategically ambitious. For the next few years, Japan's strategic objectives will have two somewhat contradictory elements; trying to keep the US-Japan relationship intact, and trying to put itself in a better position to preserve the status quo if America goes. To do the latter, Japan will need to start building a larger security role in the region. It will have to overcome resistance and suspicion from many of its neighbours — in some places deeply felt, in others mainly confected as a way of keeping Japan on the back foot. For this reason Japan is encouraging regional security forums in which it can gradually acclimatise its neighbours to it playing a bigger security role.

And Tokyo will need to overcome resistance at home in Japan to taking a wider military role. Many Japanese still hold the pacifist views which grew out of defeat in the Pacific War. Their opinions will constrain the pace at which Japan's strategic role will grow. But while pacifism has struck deep roots in Japan, it is a product of circumstances which are now passing, and it will pass with them. Pacifism is no more a permanent and immutable part of Japan's political culture than militarism. As the US security relationship fades, pacifism will fade. But Japan will not revert automatically to militarism; it is much more likely to become a normal country, like Australia, building the forces, alliances and other strategic relationships it needs to protect its territory and its long-term strategic interests..

The surest guarantee that Japan will not try to rebuild the Greater East Asia prosperity sphere is not the goodness of the Japanese people or the wisdom of her statesmen, but the brute strategic fact of China. In the 1930s and the 1940s, China was a strategic vacuum, drawing in other powers, including Japan. As Japan again contemplates an independent strategic policy, it faces a very different China: unified, prosperous, nuclear-armed and increasingly technically sophisticated. With Russia eclipsed in the Far East, China dominates Tokyo's strategic horizon. Tokyo believes, probably correctly, that in the short term the best way to constrain China strategically is to engage it as closely as possible, so it fears the American tendency to demonise China for its human rights policy and supposed military adventurism.

But in the long term Japan's overriding strategic objective must be to avoid Chinese domination of Asia, and especially of Japan. In the face of the potential challenge posed by China, Japan has no scope for an expansionist strategic policy; all its energies will be absorbed in trying to prevent China pursuing an expansionist policy.

Will China be hegemonistic? Certainly one can see why Tokyo might worry. The end of the twentieth century is bringing great opportunities to China. The continental threat from Russia which has dominated Chinese strategic policy for 30 years has receded; America's maritime domination of the Western Pacific is likely to decline; China's economy is booming and the research institutions and defence industries of the former Soviet Union are offering new generations of military technology at prices China can afford. If China's economy grows for the next 20 years at the rate of the last 14 years, it will be the richest country on earth. Of course straight lines are not always good predictions, but the world order does change, and the inability to accept that world powers can be overtaken is a common failing.

China began responding to these positive trends in the mid-1980s, by expanding and improving its naval and air forces. We can expect that trend to continue; there seems little doubt that China plans to operate aircraft carriers with fixed-wing aircraft in the not too distant future, and it will continue to expand its surface, submarine and maritime aircraft capability. Moreover the PLA is important in Chinese politics, and is well-placed to encourage the leadership to use the armed forces aggressively if they want to.

It seems that China is keen for the US to get out of Asia, and it is fair to assume that they will try to take America's place. Some believe that China's approach to maritime territorial issues such as the Spratlys shows that Beijing will be willing to use armed force to pursue regional interests, and that at least an element of China's motives in these disputes is to establish China as the pre-eminent power in the region.

But none of this is solid evidence that China now has or is likely to develop a program of regional hegemony backed by armed force. It cannot be ruled out, but nor is it sufficiently likely that it should be accepted as the basis for strategic policy making over the next few years. We just do not know whether China plans to dominate Asia. But we can say with great certainty that China will not allow another country to take America's place as the dominant power in Asia. Beijing will not necessarily fight to dominate Asia, but it will fight to avoid being dominated itself. As America departs, the only possible challenger will be Japan. So China will watch how Japan's strategic policy and force structure evolves as the US-Japan defence relationship fades over the next ten years. Japan of course will be watching China, and its strategic position and forces will be largely determined by what it thinks China is doing. Both will tend to infer aggressive motives from the other's actions, even though they may be intended to be defensive. Strategic competition between them will therefore tend to become self-sustaining.

The emergence of strategic competition between China and Japan does not require that either has ambitions to dominate the other; all it requires is that neither be prepared to risk being dominated by the other, and that each is sufficiently wary of the other's intentions to refuse each other the benefit of the doubt in assessing their strategic interests. These conditions already exist, and it seems unwise to assume they will not persist. The crux will be reached when Japan develops nuclear weapons.

The competition between these two huge powers will dominate strategic affairs in Asia for a long time to come. That will not necessarily be a bad thing. The competition between them may be quite well managed, and if so it might be quite stable. The Cold War has shown us how stable and indeed reassuring a bipolar strategic system can be. Now that the Cold War is over, it is probably the best hope we have for long-term peace and stability in Asia. That's not to say it will be perfect, or comfortable; just better than any of the alternatives.

One possible alternative which would less reliably keep the pace would be a tripolar system; they are apt to be less stable than bipolar arrangements because the third partner — usually the weakest — can change the balance quickly and unpredictably by changing sides. India is Asia's third great power, and it could complicate the balance between Beijing and Tokyo if it were drawn in. That's not certain, for several reasons. It might drop out of the first rank of powers if its economic and political developments do not keep up with China's. It may remain absorbed in the local affairs of the subcontinent or look North West to the new complexity of central Asia, rather than East to the Western Pacific; that can't be taken for granted, but it would be consistent with India's recent strategic history both before and after Independence. But if its economy grows strongly, and it chooses to look East, India would be an important factor in Asia's strategic affairs, a natural ally for Japan against their common neighbour and potentially a source of instability.

America will also retain the military capacity and influence of a great power in Asia, at least for a long time to come. But it is less likely to be drawn closer into the strategic competition between China and Japan. America's principal interest — as we have seen — is to avoid any power dominating Asia and thereby becoming a superpower. Its interests will be served by maintaining a stable balance between China and Japan. Washington will not inevitably back Japan in that competition; the links built up over 50 years of security cooperation may fade quickly once the end comes, especially if and when Japan builds its own nuclear weapons, even though that would perhaps be in America's interests. America has a long history of backing China against Japan as well as vice versa. Russia may also be drawn into the competition, but less as a player than as a victim. It is possible that if Moscow's authority breaks down in the Russian Far East, Japan and China could find themselves competing there to fill the vacuum; like Manchuria in the earlier part of this century. China and Russia could also bump into one another, and perhaps inflict bruises, in the former Soviet Central Asia; prolonged chaos there could draw both China and Russia into the affairs of the new republics to play an updated version of the Great Game.

But in general the size and power of the protagonists in Asia, and their remoteness from other centres of strategic power — Europe and the Middle East — will mean that the Western Pacific will tend to form a fairly self-contained strategic system, more isolated from strategic developments elsewhere than it was during the Cold War.

What will it mean for the rest of us in the Western Pacific? Korea is closest to the action and its strategic affairs will be completely dominated by the competition between its two giant neighbours. Even if Korea is reunified on the South's terms, and keeps to the South's path of economic and political developments, Korea will not be strong enough to make an independent stand against either of its neighbours. A reunified Korea would probably lean towards China, at least at first, because of the animosity which persists between Koreans and Japanese.

But reunification might be prevented by Japan, whose formal support for reunification sits uneasily with deep anxiety about the longer, stronger and more outward-looking neighbour that reunification would produce. Japan's interests would be better served by a divided Korea in which Japan and China could each find an ally, and Tokyo may therefore try to prevent reunification by helping the North reform and rebuild its economy so it can avoid the collapse which at present seems the most likely cause of reunification. The North Koreans would not like to rely on help from Japan, but they might prefer to keep a separate state with Japan's help than to lose everything to the South. And their potentially difficult border with China makes Japan their more natural ally.

Asian countries not sandwiched between the two great powers will still find that the competition between them is the strongest influence on their strategic affairs. Indochina is close enough to get deeply enmeshed. Japan will probably try to build an alliance on Hanoi's reliable animosity to China, and on Vietnam's appetite for investment and markets. Vietnam may prefer to look southwards for support against China, as it is already beginning to do over the Spratlys, and look for a leading role in a larger and stronger ASEAN, but that will only work if ASEAN sustains its strategic cohesion; we will look at that later. China would most naturally respond to Japanese progress in Vietnam by making its own way in Laos, which is small and weak enough to be easily dominated, even invaded if necessary. And of course China still has the Khmer Rouge to foster its interests in Cambodia.

Further away from China, the competition will be more genteel, political rather than military. But among the ASEANs, the Philippines stands out because it is further north than the others, because it is politically and economically weaker, and because it has almost no capacity to defend its islands. If the Philippines does not emulate the political, economic and military achievements of the other ASEANs, it may become a threat to regional stability by tempting other powers to intervene in its affairs, if only to pre-empt others.

Throughout ASEAN, China and Japan will look for political support, expressed perhaps in naval basing to support their efforts to protect their maritime interests in South East Asian waters. The great powers’ search for friends in South East Asia will not threaten the independence of the countries of ASEAN; except for the Philippines and perhaps Brunei they are too strong to be overwhelmed except by massive force. But ASEAN's cohesion as a regional group will not be strong enough to prevent its members siding with one great power or the other. ASEAN’s rhetorical commitment to preventing outside interference in regional affairs would be poor protection against powers which can exploit the most important divisions within and between ASEAN members — between Chinese and Malay. Singapore is bound to side with China against Japan: Indonesia and Malaysia are bound to side with Japan. Thailand will remain true to the tradition of suppleness which kept it independent throughout its history and side with neither, or both. So ASEAN’s strategic cohesion will be severely eroded as China and Japan look for friends in South East Asia.

These will not be the only strains on the strategic harmony which has been ASEAN's most important achievement. The end of the Cold War, and in particular the reduced role of the US which is the most likely result, may change the balance within South East Asia's separate strategic system. In that system, Indonesia is the regional great power, and Singapore and Malaysia must each look for ways to avoid Indonesian domination, as well as managing their own bitter and perennial bilateral disputes. ASEAN has been one way of doing that, in which Suharto's New Order Indonesia has cooperated. The FPDA has been another, and lastly Singapore especially has relied on the US presence in South East Asia to balance Indonesia's bulk in regional affairs. Indonesia has welcomed America's role in North East Asia, keeping both China and Japan in check, but has been keener to keep them out of South East Asia.

These different attitudes to the US have been brought to the surface in their different responses to the likelihood that the US presence in South East Asia will weaken after the Cold War, including the various proposals for regional security dialogue. They will persist, and may indeed be exacerbated by uncertain leadership changes in each country, but especially in Indonesia. The great contribution which Suharto has made to regional stability and prosperity through his moderate strategic and foreign policies cannot be guaranteed from his successor. We have no way of knowing what kind of leadership will emerge from the inchoate and probably protracted succession process in Jakarta: there is reason to hope that Indonesia will maintain Suharto's policies, but no basis to assume that it will. Nor is there any reason to assume that the transition itself will be smooth; if ABRI cannot agree on a new leader, a protracted power struggle is likely, and civil war not impossible.

Lastly, it's worth reminding ourselves that strategic competition between Japan and China would probably spread as far as the South West Pacific. It is quite likely that the Pacific Island countries could be wooed and cajoled by one side or both into offering political support or military access to Tokyo or Beijing, rather as the European powers did in the later nineteenth century. Such competition — much more serious than anything the Soviets ever got up to — could seriously unsettle the harmony of the South Pacific, and of the Forum itself.

4. What does it mean for Australia?

The end of the Western dominance of Asia, and the more complex, uncertain and potentially more dangerous strategic situation which will take its place, will fundamentally change the basis of Australian strategic policy. Throughout our first two centuries the essence of Australian strategic policy has been to do whatever was necessary to keep western powers sympathetic to our interests dominant in the Asia-Pacific region. This remains our policy even today; our self-reliant defence position recognises that the combat forces of our allies will not help us to defend our territory, but in defining our area of broad strategic intent as SEA and the SWP, we assume that America will continue to ensure that great powers from outside that area will stay outside it. We no longer rely on America to defend our continent, but we still rely on it to keep Asia stable so that we can defend it from the relatively small threats which might arise locally.

The strategic positions of previous generations usually seem as ridiculous and indeed as embarrassing as twenty-year-old clothes. In Australia we are inclined to mock the strategic judgments of our forebears. We hardly bother to study our strategic history. That is a mistake, because there is much to learn, whether the policies were right or wrong. But in fact Australian strategic policy has been more often right than not. The greatest mistake, in the 1930s, was made by both sides of politics in their different ways: the conservatives in relying on a Royal Navy which quite clearly could not defend Australia during a war in Europe, and Labor by clinging to appeasement and isolationism until it was too late to do anything about defending ourselves. At other times, including the First World War and perhaps even Vietnam, Australian policy makers have had the essentials right. After all, Asia has until now remained dominated by powers friendly to Australia throughout our history except for 1942.

But the terms of our strategic policy must now change. The long tradition of debates between Imperial defence and local defence, between forward defence and continental defence, between self-reliance and alliance, is now over. That will change the politics of defence, breaking a pattern which has lasted from the First World War until the last few years. We need to start again from scratch, to develop a strategic policy which will protect our interests in an Asia which is no longer dominated by a friendly outside power. This will of course be a much more 'Asian' strategic policy. For a century we have looked for enemies in Asia: we must now look there for friends too. As Bob Hawke said in 1991, we must in future look for our security not from Asia but in Asia. We are lucky that we have been prepared for this as a country by the revolution in racial attitudes over the last few decades. Its striking to see how even during the Second World War, leaders like Curtin defined our strategic interests in racial terms: on the night of Pearl Harbour he spoke of defending Australia "as a citadel for the British Race", and the racial affinity of Anglo-Saxon America was seen in Australia as the foundation of our US alliance. What Crawford wrote in the early 1930s remained true for many years after: "For Australians, pride of race comes before love of country". But at last that is no longer true; we are now probably the least racist country in Asia. That change has not come a decade too soon.

But no friends we find in Asia will take the place of the Empires and alliances which have been the foundations of our security during our first two centuries. In recent years we have developed a strategic position of "defence self-reliance within a framework of alliances". That framework is now crumbling. We must move on from defence self-reliance to strategic self-reliance. That's a big step, but we have no choice.

Defining our Interests

The first task is to define Australia's strategic interests in this new Asia. For the last two hundred years our principal strategic interest has been to encourage and enhance the strategic presence in Asia of a dominant outside power whose interests we believed correctly, although primarily on racial grounds, to be compatible and even identical with ours. Because that's been successful, we have not needed to look more carefully at the fundamental conditions for Australia's security which constitute our basic strategic interests. Now that it's over, we have to start looking at our strategic interests in Asia in a quite new and different way.

The first question to ask is whether our security would be best preserved by trying to establish a close strategic relationship with a new dominant power in Asia — either China or Japan. I don't know whether anyone has suggested that China should be it. That would be a big step for Australia: the racial, cultural, historical and political affinities which have loomed so large in ministers' speeches about our alliances over the decades have indeed been important to our strategic relationships with Britain and America. China seems just too alien, especially at the moment, to be entrusted with our strategic destiny. But Japan has been suggested, perhaps half in jest, by others. I must say I have no a priori difficulty with the idea of establishing a durable strategic relationship with one or other power.

Even leaving to one side the strictly strategic issues in such a match, the cultural and political traditions of Japan, for all their differences from our own, still make Japan the society among our fellow Asians which shares most closely the essential elements of a just and fair society: the rule of law, independent judiciary, and governments regularly answerable to the electorate. So at least in the case of Japan, it is not distaste for our putative allies which makes it impractical to look for a new great and powerful friend in Asia. The problem is more fundamental.

The imperial and alliance strategies of our first two centuries required a lot of confidence that our allies were willing and able to make a permanent commitment to Australia's security. That confidence was founded — usually well-founded — on assessments of the place of Australia in the strategic interests of our allies; Britain's concern for a prized imperial possession on the one hand, and America's view of Australia as an anchor to its Asian position in the Cold War on the other. Even so, anxiety about the serviceability of our allies' commitment to our security have been the main issue in Australian strategy throughout our history. But we have far less reason to expect that either Japan or China will see Australia's security as sufficiently central to their own strategic interests to make them reliable guarantors.

Moreover we can't be over reasonably confident that either China or Japan would be in a position to guarantee our security. Our great and powerful friends have been at least potentially dominant — or so we thought. It doesn't seem worth having a great and powerful friend who isn't. As I said earlier, there is no compelling reason to expect that either China or Japan will seek a dominant strategic position in Asia nor that they would succeed if they tried. And, more fundamentally, we'd have to doubt whether we'd want to be protected by a power which equipped itself to protect our interests by seeking domination of our neighbours. We're in a Groucho Marx-type dilemma: we wouldn't want to be protected by any power dominant enough to do it. No matter how congenial another country might be, Australia cannot in the future assume that its power will be used to support rather than injure our interests. So we are in the position Lord Palmerston described so well when he said Britain had no permanent friends or permanent enemies, only permanent interests.

It's unfashionable these days to look to Britain for lessons about how to conduct our national affairs, and indeed perverse to do so when the era of great and powerful friends is finally over. But Lord Palmerston’s remark reminds us that whatever their other failings, British strategic policy has kept Britain mostly free of invaders for nearly 1000 years. They must have been doing something right. And for all our differences, Britain and Australia do have in common the essential fact that we are both islands lying quite close to large continents. There are of course some very important differences, and we'll look at them later. But I think the best start we can make to defining our own fundamental strategic interests is to look briefly at how Britain has defined hers over the centuries, to see if we can pick up any hints.

British strategic policy — as it related to the security of its own territory rather than its overseas interests and possessions — has aimed at preserving three key interests. The first is control of what we would call the air-sea gap, the Channel, and the North Sea, "which serves it in the office of a wall or a moat". Britain has always given top priority to ensuring that it has naval superiority in its home waters to prevent invading forces landing on her island. Britain's second great strategic interest, derived from the first, has been to prevent that part of Europe closest to Britain — the Low Countries — from falling under a hostile power, because that would make it harder to maintain control of the Channel and the North Sea. And thirdly, encompassing the other two, is the great principle of preventing any power achieving dominance of Europe - preserving a balance of power among her great continental neighbours.

It's fairly clear how we might apply these principles to our own strategic circumstances. The first needs no elaboration: the foundation of Australia's security is our ability to deny passage of our air-sea gap to would-be invaders. Applying Britain's second strategic principle to our circumstances needs a bit more thought, because of the differences between Britain's strategic geography and Australia's. Britain is an island lying directly off a continent; Australia is an island lying off an archipelago which lies off a continent. That's a significant difference which we will return to, but our own strategic history suggests strongly that what we vaguely call "the archipelago" is the equivalent in our strategic position to the Low Countries for Britain. The archipelago is roughly speaking the chain of islands running from Indonesia through PNG and the Solomons into the South West Pacific — including New Zealand. It makes a big hook which reaches across our North from mainland Asia and down our east coast. Maritime and air forces operating from bases in the archipelago would be much better able to challenge Australia's command of the air-sea gap.

The domination of any substantial part of the archipelago by a hostile major power would therefore pose a substantial threat to our security. We therefore have an important and durable interest in preventing that happening. There are actually two elements to this interest because South East Asia, the most important part of the archipelago, is unlike the Low Countries to Britain, capable of posing a threat to Australia without the aid or interference of great powers from further afield. It is useful to think of South East Asia as a self-contained strategic system of its own, as well as being a part of the wider Asia-Pacific strategic system. Seen as part of the wider Asia-Pacific strategic system, our interest is to prevent the archipelago becoming dominated by an outside power. Seen as a self-contained system, our interest is to prevent any single power in South East Asia dominating the others. Indonesia is the only country likely to be able to do that. Indonesia is now too weak to pose a security threat to Australia, or indeed to its other neighbours. But if it can follow the example of Singapore, Malaysia and Thailand — and there is no reason to assume that it cannot — Indonesia will, within perhaps two decades, start to achieve the strategic potential of a great power in its own right. Under the New Order government Indonesia has not sought the regional hegemony which had seemed at times to be on Sukarno’s agenda, but a bigger and richer Indonesia, differently led, could behave differently. An Indonesia which dominated its neighbours in Singapore and Malaysia would be better able to challenge Australia in our air-sea gap. So we have a fundamental interest in preventing Indonesia dominating its neighbours.

But that's not to say that Indonesia is a natural enemy of Australia. Indonesia's place in our strategic circumstances is much more complex than that. An advantage — other than descriptive accuracy — of seeing South East Asia as a separate strategic system as well as part of the wider Asia-Pacific strategic system is the help it gives in sorting out what Indonesia means to us.

Viewed as part of the wider strategic system, Indonesia is a "natural ally": It will tend to resist intrusion into South East Asia by other Great Powers, and that is clearly to our advantage. But viewed as part of a South East Asian system, Indonesia will tend to try to dominate the region, which is not to our advantage. For that reason, within South East Asia, our natural allies are Singapore and Malaysia. The interaction of the two systems makes our relations with all the players ambivalent. Indonesia is a bulwark against intruders to South East Asia, but a potentially threatening hegemonist; Singapore and Malaysia share our concern to stop Indonesia becoming dominant in South East Asia, but could facilitate great power intrusion by seeking their support against Indonesia; and while we would prefer to keep the great powers of Asia out of South East Asia, we need to recognize that apprehension about the great powers will be the surest constraint on Indonesian strategic adventurism in South East Asia, or in the South West Pacific.

This brings us to the application of Britain's third and greatest fundamental strategic interest: to prevent any single power dominating the Continent. A power with no anxiety about rivals on the Asian continent, and able to draw on the continent's full resources, could quickly dominate the best bases for attacking Australia, overwhelm our defence in the air-sea gap, and mount an irresistible invasion. Like Britain in Europe, Australia cannot defend our territory and interests if Asia is dominated by a single great power — or a superpower as it might be. Our security would depend on their whim, and a power that had dominated Asia might not feel inclined to leave Australia independent, a hostage to fortune. This is indeed the alternate reason why we cannot look to a great and powerful friend in Asia: we could only be sure of them if they were all we had to fear.

This is a first stab at describing Australia's fundamental strategic interests in an Asia no longer dominated by Western powers. A lot more work is needed. Probably the best way to refine our ideas on these issues is to see what they mean in practice — what do we have to do to secure these interests?

Strategic Policy for our Third Century

Our new strategic environment, and the interests we need to promote to preserve our security in it, will require a revolution in Australian strategic policy. For a start it will help if we begin thinking of strategic policy more clearly as a distinct element of our international relations. Strategic self-reliance will require us to be much clearer about the distinction between strategic issues and other aspects of our international relations, just as defence self-reliance has required us to distinguish much more clearly than before between defence policy and foreign policy. Essentially, before we needed to be self-reliant in defence we could afford to be a little loose in our force-structure planning, because we were confident that other countries’ armed forces would make up for any deficiencies. Likewise we have had the luxury of a loose conception of strategic policy and its relations to others’ foreign policy because we have been confident that our most important strategic interests were being looked after by the US.

The demands of defence self-reliance have imposed a more rigorous discipline on our defence planning process, requiring us to limit the influence of broader foreign policy considerations in determining our force structure, and concentrating instead on the specific military issues involved in achieving the ability to defend our territory and direct interests. The demands of strategic self-reliance will likewise require us to distinguish more clearly the strategic issues in our overall foreign policy and to give them higher priority.

To attain defence self-reliance we had to separate defence and foreign policy: to achieve strategic self-reliance we will need to distinguish, at least in part, these aspects of foreign policy that relate to our strategic interests and view them, with defence policy, as part of a coherent whole. Three points need to be made about this process: firstly, that it is already underway in DFAT; secondly that there is a great deal of very important foreign policy which does not relate directly to strategic issues, including the whole range of trade and economic issues; and thirdly that strategic policy and other aspects of our foreign policy must never become disconnected, if only because that might lead them to pull in different directions.

The essential foundation of a self-reliant strategic position is a self-reliant defence capability. Over the last twenty years we have begun, at first rather haltingly, and now since the Dibb Review and the 1987 White Paper with greater clarity, to build defence forces which can maintain control of our air and sea approaches without the help of the combat forces of our allies. It has been essential in developing that self-reliant position that we have made the control of our air and sea approaches almost the single task that the ADF must be able to perform, so that in deciding which capabilities we need to develop, almost the sole consideration is the contribution that capability would make to the defence of our air and sea approaches or our own territory.

But our present force structure has been conceived as part of an alliance-based strategy — self-reliance within a framework of alliances — which presupposed implicitly that the competition between the US and Soviet Union would suppress any other competition for strategic influence in Asia as a whole and that Australia therefore need only concern itself with local concerns in South East Asia and the South West Pacific — our area of broad strategic interest as defined in the 1987 White Paper.

The first question that a strategic policy for Australia's third century must address is whether we need defence forces that can do more than secure our area of direct military interest. That's a very large subject; I think the best way to start in on it is to look again at Britain's long experience as an uninvaded offshore power. For at least four centuries, until very recently, British strategic debate was dominated by two lines of thought. Both aimed to ensure that Britain's three essential strategic interests were protected and in particular that no power should be allowed to dominate the continent: they differed in what role Britain's armed forces should play. One line of thinking — often but not invariably associated with the Tories — held that Britain should concentrate on maritime and amphibious operations against the ports, shipping and colonies of her enemies, on the grounds that they would minimise the risks and maximise the benefits of war to Britain, while being an adequate contribution to the efforts of European allies against the would-be hegemon of the moment. The other line of thinking held that Britain could not afford to stay out of the major land battles which must ultimately determine who rules the continent: and that Britain must therefore be prepared to commit large armies to battle on the continent. The judgment of historians like Paul Kennedy is that the continental strategists were right, at least up to a point: Britain's security required that Europe not fall under a single ruler, and that at critical times that could only be prevented with British help. So, for example, it was right to march a British army right up the Rhine, against the wishes of the Tories, to fight Louis XIV at Blenheim.

That is an entirely supportable proposition for Britain: but I do not think the same applies to Australia, at least not at present. There are three differences between our strategic position in relation to Asia and Britain's in relation to Europe which account for this. The first is that Australia, through the third largest economy in Asia, is still relatively smaller in relation to the main protagonists in wealth, and of course especially in population, then Britain was in relation to Europe, especially as she approached the great days of her power in the later seventeenth century.

Secondly, and perhaps most importantly, Britain was drawn into land wars in Europe because it was impossible to separate a struggle for control of the Low Countries from broader European battles; Western Europe at least was in effect one theatre. Britain would have held aloof from the continental battles of Europe more easily if the continent did not extend right to their doorstep in Belgium and Holland. But we differ from Britain there. We are not an island off a continent: we are an island off an archipelago, off a continent. The archipelago is our "Low Countries", but our interests in denying them to hostile forces do not require us to commit forces to continental Asia: militarily the archipelago is a maritime theatre, like our own air-sea approaches, and we can contribute to their defence very substantially with maritime capabilities.