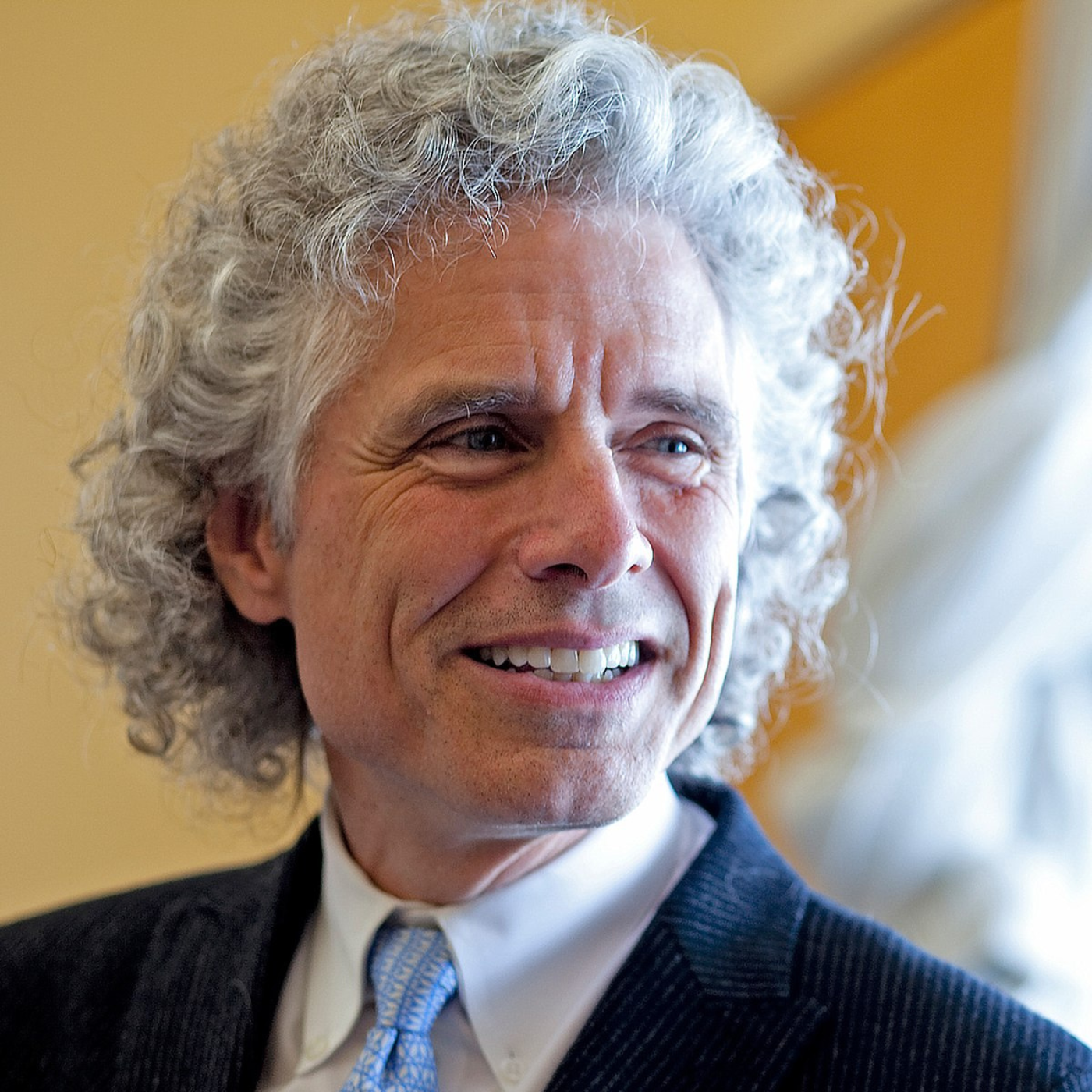

Rationality And Its Opposite — Steven Pinker (#140)

How rational are we? How can a species smart enough to set foot on the moon also be prone to conspiracy theories that the moon landing was fake? Joe speaks with Steven Pinker to discuss rationality — and its opposite.

Steven Pinker is the Johnstone Professor of Psychology at Harvard University. He is a two-time Pulitzer Prize finalist, an elected to the National Academy of Sciences and one of Time‘s 100 Most Influential People.

Transcript

JOE WALKER: I am here at Harvard today with Steven Pinker. Steve is a cognitive psychologist and one of the great public intellectuals of our age. He's authored many famous books, including The Blank Slate, The Better Angels of Our Nature and Enlightenment Now. But the first book of Steve's I read was The Sense of Style, a manual for good writing which exemplifies its own advice, and in which I learned that new information should come at the end of the sentence and that one of Steve's favourite Yiddish words is bubbe-meise. The last book of his I read is Rationality, which is going to be the focus of our conversation today.

Steve, welcome to The Jolly Swagman Podcast.

STEVEN PINKER: Thank you.

WALKER: For fun, I'd like to start with writing. To my lights, you're one of the very best nonfiction writers in the English-speaking world. I'm not sure if you remember this, but four years ago I asked you by email for advice on the process of writing a book, and you very kindly replied, "Everyone is different in their writing habits, I've found. My method is to write sequentially, from the first to the last sentence, and as intensively as possible, almost all day, seven days a week, till I'm done." Could you elaborate on why that approach works best for you and does any of your research into the human mind support that approach, or is it just arbitrary?

PINKER: Well, it couldn't support it in this: if people differ. So I couldn't root it in any universal property of human cognition if one person varies from another. I suspect it's some combination of motivation, memory, and personality.

In my case, the cognitive rationale is that writing a book involves coordinating many considerations. There's the line of argument, the actual content; there are the sources that I feel ought to be represented or that I must consult; there's the narrative arc of the prose itself; there's the sentence by sentence construction; there's the connection to other chapters in the book. I find that when I have all of those swarming around my head at the same time then I can do my best to satisfy them all. If I have to put it down and come back to it, then I've got to reassemble that whole collage. So I like the intensity of having everything in my mind for a continuous enough stretch that I can actually produce what I think is a coherent bit of writing.

WALKER: Right. That does stand out to me about your books: they're very internally coherent.

PINKER: Often that doesn't happen on the first pass. I put my books through at least six drafts before the copy editor sees it, and then there's another couple of drafts. I find—well, I shouldn't speak for everyone—but I'm not smart enough to both have a coherent line of presentation of content and to make it readable and structured. I find I have to get the ideas down first and then I can devote more attention to style, and that's why I do it in multiple passes—sometimes I'll rearrange chapters or paragraphs or sentences.

There are people like newspaper columnists who don't have that luxury, who tap out an article and touch it up for punctuation and press send. I'm not one of them, and I suspect most people are not, but it is the gift that leads some people to become pundits, bloggers, and newspaper columnists.

WALKER: On average, how many days a weeks or months does it take you to produce a first draft?

PINKER: It varies a lot by book. Some of them, like The Sense of Style, went relatively smoothly, partly because I had been thinking about the issues for a long time and there was less factual material that had to be looked up and checked. Whereas for a book like The Better Angels of Our Nature on the history of violence, I had to educate myself in a number of fields that I was not trained in: history, international relations, and affective neuroscience, that is the brain basis of emotions. So that took a great deal more.

The Sense of Style, I think I had a first draft in three months. The Better Angels of Our Nature, it took a year or so for the first draft.

WALKER: Let's talk about rationality. You define rationality as the use of knowledge to attain goals, and you take knowledge in turn to be 'justified true belief', a definition from philosophy 101. My first question is: is observation the ultimate source of our knowledge of nature? In other words, are you an empiricist in the philosophical sense?

PINKER: Not in that strict sense. Certainly in the sense that you can't do it from the armchair. That is, you can't deduce the existence of giraffes and the Himalayas and Alpha Centauri from first principles. You have no choice but to observe the world.

But on the other hand, science doesn't just consist of a long list of sensory observations, particularly since a lot of the observations that scientists make come from exotic conditions of experiments and high tech instruments. Ultimately what we want is an explanation of the world in terms of deeper principles than what we see with our own eyeballs but constantly verified for very similar to an accuracy by empirical observations. So certainly the freshman first week dichotomy between rationalist and empiricist approaches to science would be far too simplistic.

WALKER: What in your view is the correct normative model of rationality? Enrico Petracca wrote a review of the book in which he argued that you implicitly rejected Gigerenzer's ecological rationality as a normative model. Is that fair? and am I correct in placing you as an 'Apologist' in the Great Rationality Debate? Or do you kind of eschew labels there?

PINKER: I think I would eschew labels. I'm not sure what the suggestion means that as an apologist for what?

WALKER: It's kind of in the middle of the 'Meliorists' and the 'Panglossians'.

PINKER: Oh, oh, oh.

WALKER: I'm taking that label from-

PINKER: Okay, 'apologists', in that context is not particularly intuitive.

WALKER: No, it's not.

PINKER: A apologist is a defender of a particular position.

WALKER: Yeah.

PINKER: Well, I don't think the Gigerenzer ecological rationality was meant as a normative model. It was meant as a descriptive or psychological model. Although Gigerenzer is a critic of the idea that certain models that are taken as normative without question, such as the use of base rates as Bayesian priors. So for example, that the statistical prevalence in a disease in population is equated with your aprioric credence that a patient has the disease before checking their signs and symptoms and test results. That was a background assumption in a lot of the research purporting to show that humans are not Bayesian.

Gigerenzer, for example, criticises the idea that frequency in a population is a suitable Bayesian prior, but I don't think that he would criticise the very idea that there should be normative models that are distinct from the psychological processes that a typical human uses. So I don't see ecological rationality—which just to be clear, has nothing to do with being green or hugging a tree, but in Gigerenzer's definition, and that of John Tooby and Leda Cosmides, just refers to the way that reasoning takes place in a natural human environment. So that's what ecological rationality is, but almost by definition it's not a normative model.

WALKER: Although I guess you could say that Gigerenzer's 'adaptive toolkit' of fast and frugal heuristics perform better in certain environments than rational choice theory.

PINKER: Well yes, but as soon as you use the word better you're invoking some standard or benchmark against which to compare ecological rationality, which means that ecological rationality itself is not that benchmark. As soon as you ask the question, "Does ecological rationality work, does it lead to correct or justify conclusions?" well, where do those correct or justify conclusions come from? Well, they come from a normative model. So you can't get away from normative models as soon as you ask the question, "How well does ecological rationality work?"

WALKER: So what do you think the benchmark is?

PINKER: Well, one of the reasons that I defined rationality as the use of knowledge to pursue a goal, and one of the reasons that my book rationalities divided into chapters, is that there are different normative models for different goals. It depends what you're trying to attain.

So if you're trying to end up with a quantitative estimate of your degree of credence in a hypothesis, then Bayes' rule is the way to go, is the suitable normative model. If you're trying to derive true conclusions from true premises, then formal logic is the relevant normative model. So the normative models are always relevant to a goal and they are also suitable to an environment in which some kinds of knowledge are or are not available.

WALKER: Your graduate advisor, Roger Brown, once wrote a review of Lolita arguing that it was a trove of linguistic and psychological insights. I'm curious, are there any works of fiction that provide, in your view, incredibly rich depictions of your view of human rationality?

PINKER: I'm glad you brought that up, both because Roger Brown doesn't get the attention that he deserves as a pioneer in psycholinguistics and social psychology and a gifted writer (I did write an obituary of his that's available on my website), and his review of Lolita is a masterwork published in a psychology journal, a journal of book reviews, which the editor agreed to accept as long as there were psychological implications. Roger's review of Lolita is a true gem.

So let's see. Well, I'll start close to home. I learned a lot from at least two novels by my other half, the philosopher and novelist, Rebecca Goldstein. Her first novel, The Mind-Body Problem, featuring a graduate student in philosophy doing a dissertation on the mind-body problem who also faces her own mind-body problem. I'll leave it to readers to identify what that problem is. But that actually exposed me to ideas in philosophy including, for example, the concept of mathematical realism in philosophy.

The other protagonist of the novel is the husband of the graduate student in philosophy, Noam Himmel, a brilliant mathematician. In the course of their dialogues, it comes out that he, like a majority of mathematicians it turns out, believes that mathematics is not just the manipulation of symbols by formal rules, the formalist approach, although some do adhere to that, but a majority of mathematicians believe that mathematics is about something, some abstract feature of reality that they are discovering not inventing. It's just an example of one of the philosophical ideas that came out in the dialogue.

The other one is her novel, 36 Arguments for the Existence of God: A Work of Fiction, which is, in my not so unbiased view, a brilliant and very funny novel about religion and belief in God. The title alludes to a book written by the protagonist, a psychologist of religion. His book, his surprise bestseller, had an appendix listing 36 classic arguments for the existence of God and their refutations. The novel a bit, I guess, postmodernly or self-referentially, has as its appendix, the appendix to the fictitious character's bestseller.

When it came to recording the audio book, Audible had me narrate each of the 36 arguments and Rebecca narrate the responses. But it's actually, I think, the best guide to the philosophy of belief in the existence of God and it is woven into a genuinely funny and moving story.

WALKER: Any works of fiction or poems that teach Bayes' rule.

PINKER: Oh. There are sayings. I bet there are, and it might take me a while to get them, just because it is an aspect of rationality that can be rediscovered if you think about it deeply enough. But certainly there are quotes from David Hume, not in fiction. Carl Sagan's extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence. The advice given to medical students, "if you hear hoof beats outside the window, don't expect a zebra." I think it pops up in a lot of folk wisdom and I bet someone who's more familiar with fiction than I was could identify scenes from novels in which it came up.

WALKER: Have you heard of Piet Hein?

PINKER: Piet Hein?

WALKER: Yeah.

PINKER: Yes. His humorous little aphorisms.

WALKER: Yeah.

PINKER: I remember that from when I was an undergraduate and high school student.

WALKER: He calls them, these little poems, he calls them 'Grooks'. There's one that reminds me of Bayesianism, it's called the 'Road to Wisdom'. It goes: "The road to wisdom? Well it's plain, and simple to express: err and err and err again, but less and less and less."

PINKER: That's excellent. In fact, I am familiar with that and I wish it had popped into my mind as I was writing Rationality because it's a great quote, yes.

WALKER: In Rationality, there's a wonderfully lucid explanation of Bayes' theorem. Could you summarise that explanation briefly?

PINKER: Sure. It sounds very scary when you call it a theorem, but the goal is simply how do you assess your degree of belief in a hypothesis in light of evidence? The key insight of the eponymous Reverend Bayes is that your degree of belief can be treated like a mathematical probability—that is a number between zero and one—and the warrant of your belief by the evidence can be expressed as a conditional probability—that is, not just what is an analogy to what are the chances of something happening, but "if such and such is true, then what are the chances of such and such happening?" You just import that bit of mathematics (it's almost less than two in any introduction to probability), and you equate a degree of belief with probability, warrant of that degree of belief by evidence as conditional probability, and Bayes' rule kind of falls out. Just a little bit of high school algebra.

What it basically says is what you want, the desired output, is: how much should I believe in this hypothesis on a scale of zero to one? You can say from zero to a hundred if you just multiply it by a hundred. You should estimate that by three other concepts, each of which could be quantified as a probability. The first is your prior, that is before you even looked at the evidence how confident were you in the hypothesis based on everything you believe, everything you know, right up until the moment of peering at the new evidence. So those are the priors, that's number one.

Number two is the likelihood. That is: if the hypothesis is true, what are the chances that you'd be observing the evidence that you are now observing?

You multiply those two together, and you divide by the commonness of the evidence. That is, how likely is it to observe that evidence across the board whether your idea is true or false? So in the case of, say, diagnosing a disease, some symptom that is extremely common, like headaches and nausea and weakness and even back pain, since there's so many different conditions that can cause that—like the speed-mumbled proviso at the end of ads for drugs, they always go through a list of symptoms and it seems to be the same list of symptoms for every drug, just showing how common it is—since that goes in the denominator: big denominator, small fraction. What it means is if you're looking at a symptom that is very, very common, you should not have a lot of credence in any particular diagnosis.

So anyway, those are the three terms that go into Bayes' rule. Again, it sounds more complicated than it is. The reason that people have to be reminded of it is that, as Tversky and Kahneman point out, and I think it's true despite Gigerenzer's pushback, we do have a tendency to discount the priors, the first term in the equation, that is how likely is the hypothesis to be true based on the background statistics, and we glom onto the likelihood, the stereotype.

We tend to confuse 'P implies Q' with 'Q implies P'. That is, for example, if an art major tends to like spending summers in Florence, we assume that someone who likes to spend summers in Florence must be an art major. That would be over-emphasising the likelihood, namely the probability that if you are an art major you enjoy spending summers in Florence, neglecting something that is highly relevant, namely 'what percentage of students are art majors in the first place?' Someone who likes to spend summers in Florence are actually more likely to be a psychology major despite the stereotype, simply because there are probably 50 psychology majors for every art history major, and we tend to not think that way unless we're reminded.

WALKER: What do you make of Jimmie Savage's distinction between 'small worlds'—that is, worlds in which you can 'look before you leap'—and 'large worlds'—that is, worlds in which you have to 'cross that bridge when you come to it'. In his book, The Foundations of Statistics, he says it would be "utterly ridiculous" to apply rational choice theory and Bayesianism to large worlds.

PINKER: Well, that's certainly true in the sense that there could be a vast amount of knowledge that we don't have and can't easily get. The world is complex, there are multiple contingencies, no one but God knows them all, and so it can be foolish to act as if you know all of the relevant probabilities when the world is just too complex to allow them to be estimated. So that is certainly true.

WALKER: How do we make sense of Tetlock's superforecasters then? Are they not operating in large worlds? Maybe you could say, in the words of John Kay and Mervyn King, that they're solving very contained puzzles as opposed to open-ended mysteries? Or is there something maybe statistically deceptive about Brier scores? Or how do you square that circle?

PINKER: Well, they are the exception—I suppose you could call it the exception that proves the rule in the sense of testing it—namely by immersing themselves in relevant data that most of us tend to ignore they do a not bad job. Of course, they themselves would be the first to admit that they can only give a probabilistic estimate, that their performance can't be ascertained by one prediction, but only by the entire portfolio of predictions because even the best of them will get some things wrong. As Tetlock notes, their accuracy falls off to chance beyond a time horizon of about five years, including the best of them.

But you in a sense answered your own question by the fact that forecasting tournaments have concrete benchmarks and we actually can answer the question did the prediction turn out correctly or not? The fact that it does turn out correctly at a greater rate than chance shows that we can know enough about relevant aspects of the world that we're not just throwing darts.

WALKER: Yeah, I guess it depends how you interpret those results. Maybe you say that they are somehow less interesting than truly large world scenarios.

PINKER: Well, they are pretty large worlds. I mean they do make predictions about whether a war will take place or a recession, election results, and those are pretty large and consequential.

Now the thing is that superforecasting is really hard because these are large worlds. But not impossible. Savage writing, when, in the fifties? Our state of knowledge is vastly richer than it was in that time and our means of estimating things. Again, even the best of superforecasters is nowhere near perfect and falls to chance within five years, so he's right that this is extraordinarily difficult, but it'll be too pessimistic to say it's impossible with any data on any time scale.

WALKER: You spoke about the three different terms in the Bayesian formula. Where do priors come from? If I think of your book The Blank Slate, is there a sense in which some priors might be innate? For example, babies would tend to focus on humans in the room? Or I think Gigerenzer talks about an illusion where people feel as if a source of light is always above them?

PINKER: Yes. There, as with all nature-nurture tensions, it's very hard to tease them apart in our world because of course we grew up in a world in which the illumination does come from above, whether from the sun and the sky and the moon or from artificial lighting. You could test that by bringing up animals in an environment in which the source of illumination was always from below, that is maybe an illuminated floor, to see whether those animals had more difficulty perceiving shapes when the light did come from above, the mirror image of our situation.

But nonetheless, going back to the conceptual point, yes, there probably are some priors that are innate. That is what natural selection would tend to select for that we don't start from scratch. Each one of us as a baby, we at least know what to attend to, what to concentrate on, what kinds of correlations to pay attention to.

There is a school in cognitive psychology of Bayesians, such as my sometime collaborator Josh Tenenbaum at MIT, who makes the implicit equation at least between Bayesian priors and innate knowledge, that's what innate knowledge would consist of. I mean, he wasn't the first to make that equation, but it is a natural one and it's an empirical question how rich those priors are, that is how much innate knowledge we have.

WALKER: What is the most pervasive cognitive bias?

PINKER: Probably the myside bias, at least that's the claim of Keith Stanovich in his book The Bias That Divides Us. He suggests it's the only bias that is independent of intelligence. All the others, if you're smarter, you're less vulnerable to them. But not from myside bias. You just become a more clever litigator or advocate and come up with better and better arguments for the sacred beliefs of your tribe.

WALKER: Is the evolution of myside bias better explained by multilevel selection theory than by selfish gene theory?

PINKER: No, I don't think so. I have pretty strong opinions on multilevel selection theory, which I think is incoherent. I have an article called 'The False Allure of Group Selection'.

WALKER: On edge.org.

PINKER: On edge.org, yeah. It's also on linked on my website. Group selection of course being one of the higher levels of the so-called multi-level selection.

No, because for one thing, a lot of myside bias is the esteem that you get within your group and conversely the ostracism and even social death that comes from embracing a heterodox belief or denying a sacred belief. So that certainly affects the status and ultimately the reproductive success of the individual.

Also even in cases where you are making your group more formidable that as long as the interests of yourself and the group don't diverge, the interests of the group and the interests of the individual are the same. So you don't need group selection to account for it even if your arguments are increasing the prestige or influence of your group. By doing that, they're influencing your own ultimate influence.

WALKER: This question is intended in a spirit of sheer playfulness. So, like me, you locate yourself on the centre-left of the political spectrum. For example, you're on record as being the second largest donor to Hillary Clinton at Harvard. But within academia you're often attacked for not being left-wing enough. For example, there was a pathetic attempt to remove you from the Linguistic Society of America's list of distinguished fellows in 2020. So my question is why not bite the bullet and move to the centre-right, at least socially? Hang out with the Niall Fergusons of the world where you'll be at less risk of cancellation. Or is a form of myside bias holding you back?

PINKER: Well, it could be. As with all cases of myside bias, I might be the last person to ask, because I would be so immersed in it that I couldn't objectively tell. Niall Ferguson is a friend. I am binary, that being here at Harvard University and the People's Republic of Cambridge as it's sometimes called, I am immersed every day in not just left of centre, but often hard left colleagues and students. But at the same time, I do pal around with people on the right, libertarians. Not as many national conservatives of the Trump variety, but certainly have a lot of friends who are right of centre.

Well, I try not to fall into a single tribe because it clouds your judgment. It maximises myside bias. I can't claim, just as no one can claim, to be free of it, but I do take steps to minimise it. I expose myself to opinions on different parts of the political spectrum. I subscribe to The New York Times and The Guardian, but also to The Wall Street Journal and The Spectator and try to pick and choose the ideas that I think are best supported. Over the course of my career, I've changed my mind on a number of things.

WALKER: If I had to guess, and you can correct me if I'm wrong, but you would pick the availability bias as the second most pervasive bias after myside bias?

PINKER: Yeah. I think if forced to choose I'd probably land on that.

WALKER: Could this perception just be the result of the availability bias itself? Maybe there's something more salient about examples of the availability bias because they seem more blatantly stupid, whereas in comparison, representativeness is more contested: like you could say the Linda problem substantially evaporates when it's presented in frequentist terms.

PINKER: That's right and that's why I would be hesitant to rank the different biases. Indeed, it's a common question people ask me, "What's the most influential book you've ever read? What's the most influential thinker that has shaped your ideas?" It always sets me back on my heels because I could easily name a bunch of influential books or influential people or formative experiences, but unless you've actually sat down and ranked them, which is not something that you naturally do, there's no ready answer to that style of question.

WALKER: Right.

PINKER: Likewise, yeah, maybe availability isn't second, maybe it's third.

Maybe it is all the examples of fear of nuclear power because of Chernobyl, fear of going into the water because of a publicised shark attack. Those themselves are highly available and maybe that's why it's a tempting first answer, but it may not be the best answer. In terms of the Linda problem, I don't know how many of your listeners are familiar with it?

WALKER: Worth explaining.

PINKER: There aren't a lot of Lindas anymore, that's a kind of a baby boomer female name. We can also call it the Amanda problem. This is the stereotype of a social justice warrior philosophy major, is she more likely to be a feminist bank teller or a bank teller. Maybe even have to replace bank teller now because there aren't as many bank tellers as there were in the 1970s.

WALKER: Crypto trader.

PINKER: Yes. Fine. The fallacy called conjunction fallacy is people tend to say it's likely that she's a feminist bank teller than a bank teller even though that violates the axiom of probability that the probability of A and B must be less than or equal to the probability of B alone. It's thought to be driven by stereotypical thinking, but it's prime violation of Bayesian reasoning.

Gerd Gigerenzer has suggested that it goes away when instead of asking the question 'What is the probability that Linda is a feminist bank teller?', you say: 'Imagine a hundred people like Linda, what proportion of them are feminist bank tellers?' Turns out, and I repeated this observation from Gigerenzer in my book How the Mind Works, turns out it's not exactly right and there was a adversarial collaboration between Kahneman and one of Gigerenzer's collaborators, Ralph Hertwig, where they actually agreed on a design of a set of experiments to see who was right and who was wrong. It turns out the conjunction fallacy is greatly reduced when you reframe it from the probability of a single event, Linda, to frequency in a sample of women like Linda. It doesn't go away, to my own surprise.

So I don't want to say that Kahneman had the last laugh because it's certainly true that it was reduced—as Kahneman and Tversky noted themselves—to my surprise, it doesn't go away. I think I was probably as surprised as Hertwig. So we shouldn't conclude that it's just an artefact of our inability to conceptualise a propensity of an individual as a probability. Though, I think that indeed is a factor.

WALKER: Do you think Michael Lewis' book The Undoing Project was fair to Gigerenzer?

PINKER: I don't think it explained his challenge well enough. So in that sense, no.

WALKER: And therefore you could probably say that Gigerenzer remains underrated compared with Kahneman?

PINKER: Absolutely, yes.

WALKER: In the mainstream.

PINKER: I think that is right, yes. It does. Gigerenzer has a number of important lessons, including the psychological naturalness of frequencies as opposed to single event probabilities. The fact that there are ways of making probability more intuitive that ought to be maximised in education, in public health messaging. That the normative models in cognitive and social psychology tend to assume are the correct benchmarks ought themselves to be questioned. That is the textbook Bayesian analysis, really the 'correct answer'? Likewise, for many of the classic demonstrations of human irrationality, it could be that the Joe or Jane on the street is being more rational than the experimenters who devised the challenge.

WALKER: To what extent are the availability heuristic and the representativeness heuristic the same thing? Maybe they share an underlying mechanism to do with memory or the structure of our neural network?

PINKER: They are probably related. The availability bias tends to be defined in terms of particular events or occurrences, representativeness more of a generic stereotype. Now they are related in that our stereotypes tend to come from an accumulation of examples and for decades there's been a debate in cognitive psychology as to whether stereotypes consist of one generic representation with some open slots, like your stereotype of a dog is some sort of morphed composite of all the dogs kind of superimposed in averages, or whether stereotype thinking comes from exemplars, that is lots of examples that are all in the brain and a process that accesses them by comparing an instance simultaneously against all the instances stored in memory.

So that debate on conceptual representation in cognitive psychology would be relevant to the question of whether availability and representativeness are the same heuristic, in terms of their psychological mechanism, or distinct.

WALKER: This next question is also intended in a spirit of sheer playfulness. So could the temptation to extrapolate the Long Peace—that is, the post-1945 decline of wars among great powers and developed states—could extrapolating it into the future simply be the result of representativeness bias—that is, judging likelihood by similarity?

So to explain by analogy, Andre Shleifer and Nicola Gennaioli have some work where they apply representativeness to extrapolation in asset markets and they look at how people predict future uncertain events, like rises in asset prices, by taking a short history of data and then asking what broader picture the history is representative of. When people focus on such representativeness, Shleifer argues, they don't pay enough attention to the possibility that the recent history is generated by chance or a random process rather than by their model.

So, to continue the analogy, if a company has a few years of earnings growth, investors might conclude that the past history is representative of an underlying earnings growth potential when maybe it's nothing more than random.

PINKER: It is possible because we're talking about a stochastic process in the sense of being probabilistic over time. In The Better Angels of Our Nature I raised that question and tried to deal with it as best I could in with some pretty crude statistics, namely if you estimate the underlying rate of war up to the moment that historians identified as the onset of the Long Peace, namely at the end of World War II, and then asked what are the chances that we would observe a rate of war as low or lower as we have observed since then in a rather simple chi-square analysis it turns out to be extraordinarily unlikely on the assumption that the probability has not changed.

Now that was the best I could do in 2010, and it's not the best statistical analysis. Since then, though, three different statistical teams have used a fairly recent and more exotic technique or a family of techniques called change-point analysis. Namely, if you were not to identify a priori what your change point is, and there is always a danger that if that is identified post hoc then you could just eyeball the point at which a density of events seems to change and compare before and after, and that could lead to a statistical artefact.

In the case of the Long Peace, I argued that it isn't post hoc, that World War II really did qualitatively change a lot. But still, a skeptic could say, well, maybe you only are saying that because that's when the frequency of war appeared to change.

So in change-point analysis, you can without priors look at a time series and estimate whether there is likely to be some change in the underlying generator, that is in this case how likely are nations to go to war? All three of them, I did identify a change point. They differed somewhat in where when the change point was, whether it was the late forties, the early fifties. A third identified the sixties as being the change point, but all three did identify a change in the underlying frequency, their underlying parameter that would generate the frequencies, that is the propensity of nations to go to war.

So that ups the confidence that this isn't simply over-interpreting a temporary stochastic paucity in the observed data.

WALKER: So you consider Herb Simon's essay on the architecture of complexity to be one of the deepest you've ever read. Why is it mandatory reading for any intellectual?

PINKER: Well, it explains and unifies so many disparate phenomena according to a principle that is fairly easy to grasp but that has far reaching implications. That being that any complex system is likely to be composed of a relatively small number of subsystems, each one of which is itself composed of a relatively small number of subsystems. That is the only way in which complexity can be self-sustaining, because a system that's just built from scratch out of hundreds or thousands of parts would be vulnerable to any degradation or damage, bringing the whole thing crashing down.

Whereas if a system is more modular, hierarchically organized, such as the body consisting of systems, which consist of organs, which consists of tissues, which consists of cells, which consists of organelles, then one part can be damaged without bringing the whole thing down. This is true of societies, of corporations, of universities, of galaxies.

Although Simon concedes that a possible limitation is that these might be the systems that are most amenable to human understanding, so there is a possibility that there's ascertainment bias.

WALKER: You've been critical of the effective altruism movement for lurching too far from its global health and development roots towards cause areas like preventing existential catastrophe and unaligned AI. I'm curious, what are your specific object-level critiques of longtermism?

PINKER: Well yeah, as a number of people have noted, effective altruism has gotten weird. That is, prioritising the existence of trillions of consciousnesses uploaded to a galaxy-wide cloud as opposed to reducing infectious disease and hunger now.

Among the problems are that our ignorance increases exponentially with distance into the future. That is, 10 things might happen tomorrow, for each one of those 10 things, another 10 things could happen the day after tomorrow, and so on. If our confidence in any of those things is less than one, then our confidence in anything several years out quickly asymptotes to zero, and to make decisions now about what might happen in a million years, a thousand years, even a hundred years, even 10 years is probably a fool's errand. Therefore it can be highly immoral to make decisions now based on a scenario of which we are completely ignorant, at the expense of things that we know now, namely people are starving and dying of disease who could be spared.

A lot of the scenarios having to do with superintelligence I think rely on a completely incoherent notion of intelligence. I explain this in a few pages in Enlightenment Now, that the notion of artificial general intelligence or superintelligence is a kind of mystical magic, it's not rooted in any mechanistic conception of how intelligence works. Many of the scenarios envisioned, such as a perfect understanding of our connectome and the dynamic processes of the brain that could be uploadable to a cloud are fantastical. Namely, they are almost certain never to take place as opposed to almost certain to take place given the scale of the problem, the vastness of our ignorance, the formability of the technical challenges together with our philosophical ignorance as to whether a replica of our connectome running in the cloud would even be conscious, or if it did, whether it would have our consciousness.

So the moral, since morality is driven above all by consciousness, that is by suffering or flourishing, to make decisions based on the enormous philosophical uncertainty of where our consciousness resides, together with the, I think, technological naivety of how likely these scenarios are to unfold, I think means that is an example of EA going off the rails.

Now, by the way, it doesn't mean we shouldn't worry about real existential risks like nuclear war or pandemics. But there, the short to medium term and the long term align, and longtermism is irrelevant. It would really suck if all life were to be extinguished by a nuclear accident. Even if 99% were. This is something we should work very, very hard to prevent and the hypothetical disembodied souls in the cloud in a million years is kind of beside the point. You should still work to end to prevent nuclear war or a highly damaging pandemic.

WALKER: In a paper called 'Innovation in the Collective Brain', Michael Muthukrishna and Joe Henrich argue that innovations aren't the work of lone geniuses but rather emerge from our societies and social networks, or what they call the 'collective brain'. Individuals who seem like heroic inventors can really be thought of as the products of serendipity, recombination, and incremental improvement. What do you make of their argument?

PINKER: Oh, it's a false dichotomy. I mean, it's just obviously true that no solitary genius can invent anything from scratch, and no one ever said that that was true, so this is a true straw figure. But nor is it true that innovators are commodities, that any old person can invent anything. There are genuine differences in intelligence that have measurable consequences in the likelihood of producing an innovation. We know this from Camilla Benbow and David Lubinski, Studies of Mathematically Precocious Youths, they really do end up with more patents than non-precocious youth and together with the personality traits that are necessary for innovation, such as conscientiousness, self-control, perseveration.

So this is a complete and utter false dichotomy. You need brilliant people working in networks of sharing information and building on past advances to get true innovation.

WALKER: If we are reasonable beings, why do certain true ideas that seem so obvious in hindsight take so long to appear in the historical record? For example, arguably, probability theory, or just simply the idea that all human beings are equal?

PINKER: Our instincts militate against them. That is, we do have tribalism that goes against the idea of universal equality. We have availability and representatives and so on that push back against probability, at least as abstract formal all-purpose symbolic formulas. When it comes to our own everyday lives, when it comes to giving equal consideration within the clan, when it comes to assessing probability of things happening to us that we experience, we're not so bad. But generalising them using an abstract formula depends on networks of global cooperation that make other people bring other people into our circles of sympathy and depend on the accumulation of knowledge, including tools such as literacy, mathematics that multiply the abilities that we have. These took time to develop as transportation, communication, literacy, written records, education were built piece by piece over time.

WALKER: Steve Pinker, thank you so much for joining me.

PINKER: My pleasure. Thank You.