Why Great Powers Sleepwalk to War — A Masterclass with Hugh White

2,500 years of strategic history, 11 books, one afternoon

Hugh White is Australia's foremost defence and strategic analyst. He has served as senior adviser to Defence Minister Kim Beazley and Prime Minister Bob Hawke (1985–91), Deputy Secretary for Strategy and Intelligence in the Department of Defence (1995–2000), and founding Director of the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (2001–04). As Deputy Secretary, he was the principal author of Australia's 2000 Defence White Paper. He is now Emeritus Professor of Strategic Studies at the Australian National University, where he has taught since 2005. His books and essays include The China Choice, How to Defend Australia and, most recently, Hard New World: Our Post-American Future.

Months before we sat down to record, I asked Hugh for the books that had most shaped his thinking on strategy, international relations and defence policy. He sent me a list of eleven. In this episode we work through them one by one, book-club-style — what each book argues, what it gets right and wrong, how it influenced Hugh's worldview, and what it says about the big questions: Why do great powers start wars that ultimately destroy their status? What really drives the collapse of international orders? Can change be managed peacefully? And how should Australia and America respond to the rise of China?

I really enjoyed preparing for this episode. I’m embarrassed to say I didn’t have a better-than-average understanding of the causes of WWI or WWII beforehand. If you’d asked me to explain 1914, I might have given some vague answer about the assassination of Franz Ferdinand, half-remembered from high school history class. For 1939, I probably would have said ‘Hitler’. This episode has convinced me that a decent understanding of the causes of the world wars should be table stakes for public intellectuals and political leaders alike. (And to be clear, I still don’t feel like I understand them as much as I’d like!)

As for Hugh, Hugh is a mensch. I’d long been aware of him and had read some of his essays over the years. It wasn’t until last year — preparing to interview Richard Butler — that I read parts of Hugh’s 2019 book How to Defend Australia. That experience elevated him to a special group of intellectuals in my mind: truly independent thinkers. He wrote a chapter about the circumstances in which Australia would be justified in considering exiting the NPT and acquiring nuclear weapons. It’s written with an appropriate mood of gravity and sombreness, and it showed intellectual bravery — that he’s willing to follow the argument where it leads and to leave no stone unturned when it comes to keeping the torch of liberty aflame in the South Pacific. My respect for him was much deepened after that.

I hope you enjoy our conversation!

Resources

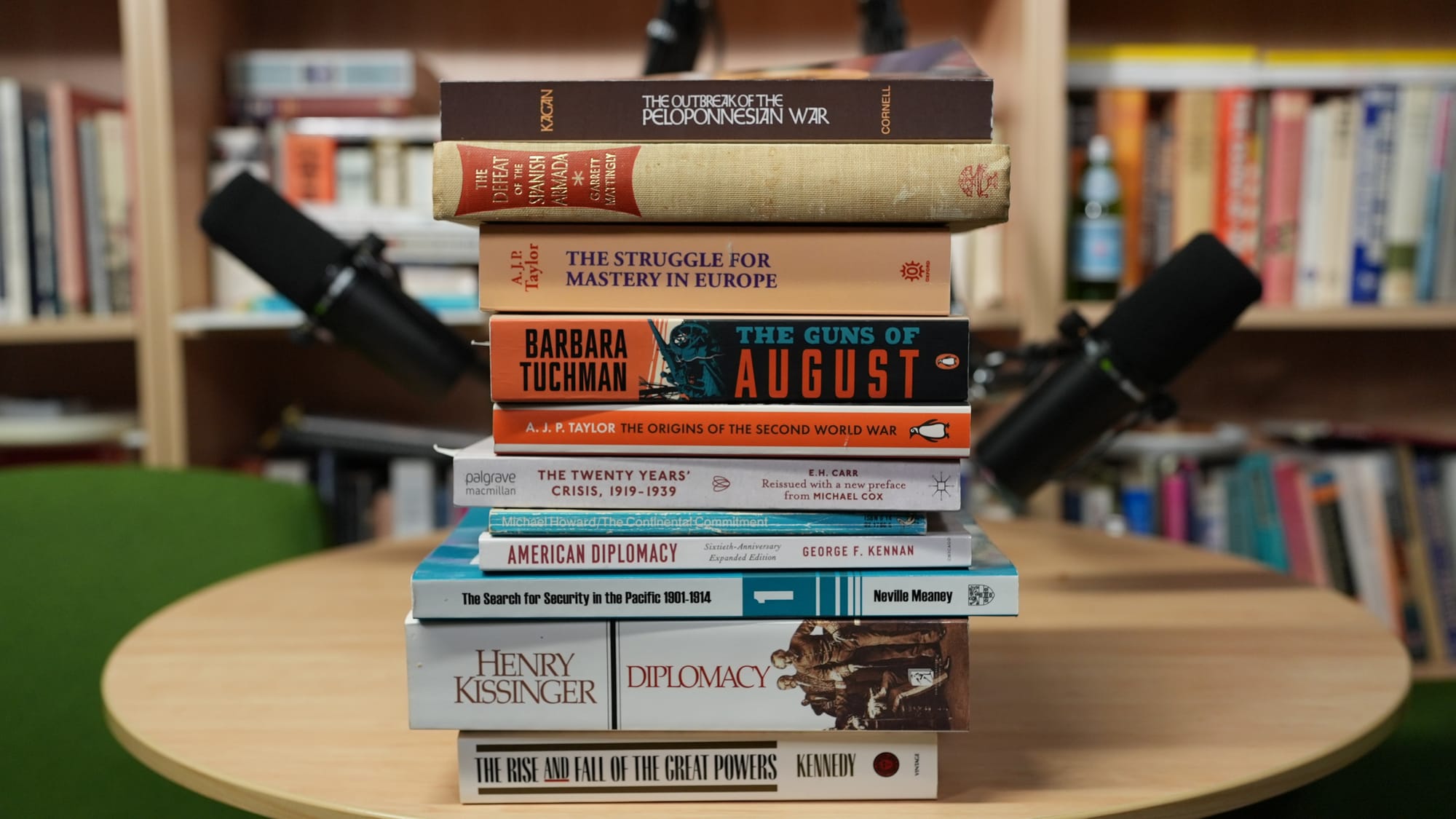

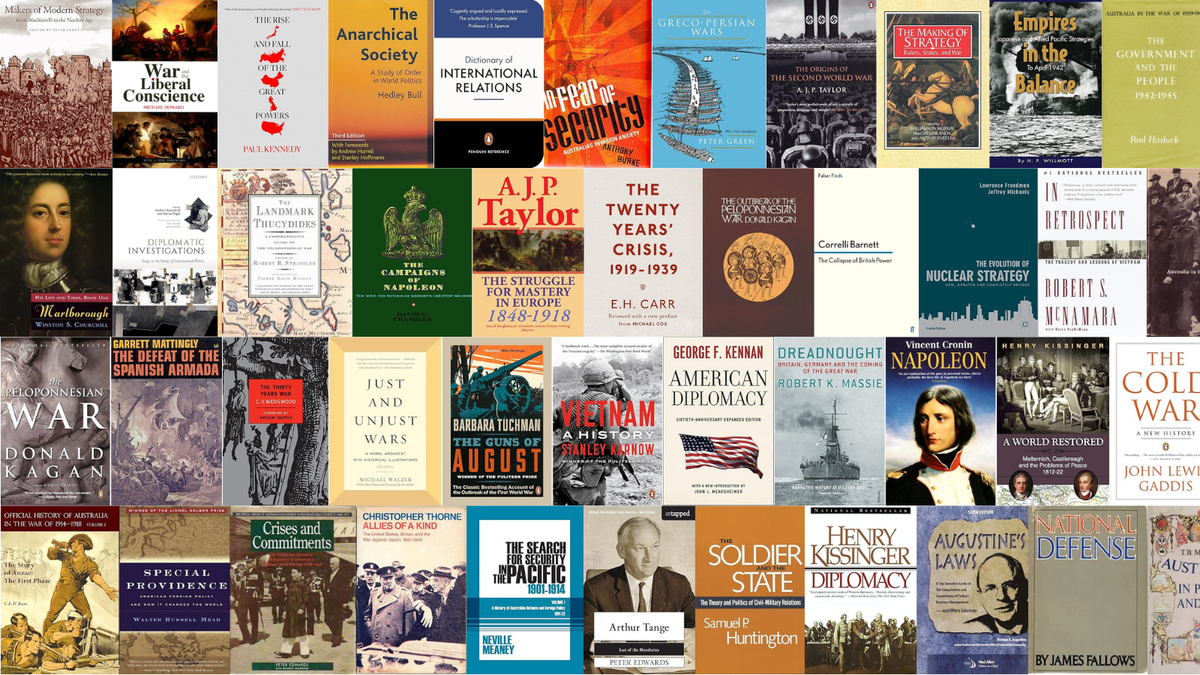

Short list: 11 books

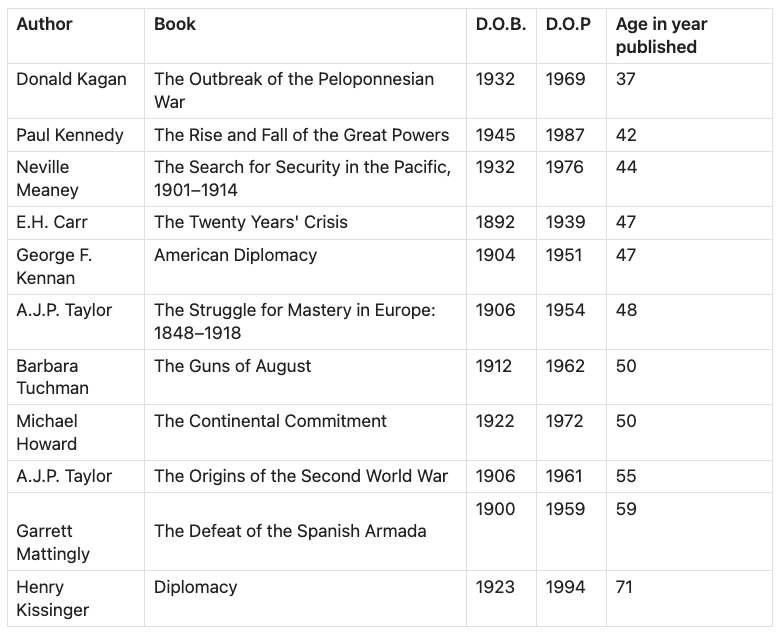

Donald Kagan – The Outbreak of the Peloponnesian War

Garrett Mattingly – The Defeat of the Spanish Armada

A. J. P. Taylor – The Struggle for Mastery in Europe: 1848–1918

Barbara Tuchman – The Guns of August

A. J. P. Taylor – The Origins of the Second World War

E. H. Carr – The Twenty Years' Crisis

Michael Howard – The Continental Commitment

George F. Kennan – American Diplomacy

Neville Meaney – The Search for Security in the Pacific, 1901–1914

Henry Kissinger – Diplomacy

Paul Kennedy – The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers

Long list (with Hugh's annotations)

View the long list here.

Hugh's 1993 Tathra note

Read the note here.

Video

Sponsors

- Eucalyptus: the Aussie startup providing digital healthcare clinics to help patients around the world take control of their quality of life. Euc is looking to hire ambitious young Aussies and Brits. You can check out their open roles at eucalyptus.health/careers.

- Vanta: helps businesses automate security and compliance needs. For a limited time, get one thousand dollars off Vanta at vanta.com/joe. Use the discount code "JOE".

Transcript

JOSEPH WALKER: It's my great honour to be here with Hugh White. Hugh is maybe Australia's most prominent strategic thinker. He has been thinking about Australian strategic and defence policy for decades. He's held positions at the pinnacles of multiple different domains — in government, the public service, journalism, academia, think tanks.

He was an advisor for Kim Beazley when Kim was Defence Minister, for Bob Hawke when Hawke was Prime Minister. He is currently an emeritus professor at the Australian National University. And he's the author of multiple books and Quarterly Essays.

We're doing something a bit different today.

Hugh, I'd actually been wanting to do an interview with you for years. But you've done your fair share of media and I wasn't sure how much I could add to that body of work.

And so I asked our mutual friend, Sam Roggeveen, you know, “Is there a great interview kind of locked up inside Hugh?” And Sam said that, at least to his knowledge, no one had gone into your philosophical and historical underpinnings.

That gave me the idea, why don't we sit down and talk about the books that have most influenced you, most shaped your worldview, because I think it'll be increasingly the case over the next few decades that people will look at you as a very prescient prognosticator.

HUGH WHITE: I hope not [laughs].

WALKER: [laughs] Well, exactly. That's right. I guess there's a distinction between what you think might happen and what you want to happen.

WHITE: Exactly.

WALKER: Which maybe sometimes people forget.

WHITE: Yes.

WALKER: But I think it will be really interesting just to look at the sort of intellectual bedrock underneath your views.

Just for people who aren't familiar, maybe the thing that you've been most clearly and consistently describing in the Australian discourse over the last few decades has been the rise of China, how China is going to become the dominant power in East Asia and the Western Pacific, and how Australia needs to adjust accordingly.

So I asked you whether you could put together a short list of the books that have most influenced you.

For people [not] watching the video, Hugh and I can't quite see each other right now because there's a stack of books between us on the desk [laughs]. So, this is the “short list”.

WHITE: [laughs]

WALKER: So, we have 11 books and we're going to go through and discuss each of them. I've endeavored to read at least parts of all of these books, if not the whole thing. And I guess we’re going to compare notes and then we'll discuss some specific questions about each book. And then at the end, I've got some general questions.

So, are you ready?

WHITE: I'm ready to go. Thanks very much. Really appreciate the opportunity. It's been a very interesting exercise for me to revisit these books and think about how one's ideas have developed.

Donald Kagan: The Outbreak of the Peloponnesian War [03:44]

WALKER: The first book is The Outbreak of the Peloponnesian War by Donald Kagan.

So, for each book, I'll give a brief background of the author, a blurb for the book, just so our audience has context, and then we can start talking about it.

First published in 1969, the author is Donald Kagan. He was an American historian and classicist at Yale specializing in ancient Greece. And he taught a very popular course at Yale for decades called The Origins of War (I think one of the most popular courses at the university, period).

He wrote four volumes on the Peloponnesian War, and this was probably his best-known scholarly work. And this is Book One of those four volumes.

If I condense the thesis down into a sentence or two, for me, the question he's trying to answer is, at what point did war between the Athenian Empire and the Peloponnesian League become inevitable? So, what was the threshold?

And he concludes, in contrast with Thucydides, that the war was not inevitable. It was avoidable, possibly right up to the last minute, potentially even after the Megarian Decree, when the second Spartan embassy requested that the Athenians rescind that.

We can explain what all that means. But my first question is, do you buy Kagan's basic account of the causes of the war?

WHITE: Yes, I do. I mean, what he's trying to do in the book, and the reason why he wrote a whole book on the outbreak, as you say, as the first volume of his multi-volume analysis of the whole thing, is to interrogate this line in Thucydides, very famous line in Thucydides — who, of course, was the Greek general who himself was involved in the war and wrote, in some ways, the first real history of anything and a wonderful book in itself. (It’s sort of perverse of me in some ways to have suggested Kagan rather than Thucydides as the book that has most shaped my thinking about these things.)

But what Kagan set out to do in the book was to interrogate the proposition that is in Thucydides. Thucydides said the rising power of Athens and the fear that caused in Sparta made war inevitable. At least, that's the way his Greek is usually translated into.

WALKER: And then there's obviously a debate around whether he meant inevitable literally or just as something like “very likely”.

WHITE: Exactly, exactly.

And so the whole book really is an interrogation of that question. And in the process, what he does is to give a very detailed — I mean, considering we're talking about the fifth century BC, astonishingly detailed — account of what steps actually led to the war.

And as you say, he comes down very strongly on the idea that it wasn't inevitable, that there are all sorts of points at which the war could have been avoided.

It's a terrifically interesting analysis from my point of view, because it has throughout history, since then, always been seen as such a sort of quintessential example of strategic analysis. I mean, Thucydides' book is such a quintessential, sort of primary example of strategic analysis. But also because it does seem to resonate so directly with the choices that we face today. People addressing the US-China rivalry have spoken very explicitly about Thucydides' Trap.

And not just the scholars. Xi Jinping on a visit to the United States a few years ago, in a speech in Seattle, specifically spoke about Thucydides' Trap. Is war between a rising power and an established power — a rising power like China and established power like the United States — inevitable?

And another US scholar, Graham Allison of Harvard, wrote a book which has become very famous in which he does specifically analyse that question.

So, to go back to the original, to see Kagan's painstaking analysis of what was going on in fifth century Athens, what drove the slide to war, and which was, indeed, a catastrophic war for both sides in the end. The way in which he unpacks Thucydides' initial distinction between ultimate causes and proximate causes... the big movements in history in the background, and then the little things that happen day by day.

I found it when I first read it — which was sometime in the '90s, when I was starting to think about the implications for Australia of the rise of China, and what that meant for America's role in Asia and so on — a very compelling model for how you think about these questions.

And indeed, his answer is extraordinarily complex as you just sketched. There are very big questions about the way in which Athens' position in Greece after the Persian Wars, after the victory over Persia, evolved: the creation of Athens, the Athenian-led alliance, which was really an Athenian empire; the challenge that posed to the traditional Spartan position in the Peloponnese; the fact that there were different kinds of power… Sparta is quintessentially a land power. It's got a great army. Athens is quintessentially a naval power, a maritime power, which itself is very, very resonant.

And the way in which he describes those background forces and then all sorts of stuff happening. And what's fascinating about the outbreak of the Peloponnesian War is it starts with an internal dispute in a two-bit little town that nobody had heard of called Epidamnus, which is on the coast of what's now Albania.

And it drags in other countries — cities. It drags in Corcyra, what's now Corfu. Drags in Corinth.

By dragging those two in, the Athenians are dragged in. It's a fascinating account as to why that little dispute drags these other powers in.

And then that starts to worry Sparta, and then the Athenians do some stupid things, as Kagan argues. The Corinthians do stupid things. The Corcyraeans do stupid things. The Athenians do stupid things.

Oddly enough, it's the Spartans who come out kind of as not exactly the heroes, but they do fewer stupid things than anybody else.

And that combination of grand shifts in the distribution of wealth and power on the one hand, and events, and people's response to them — failures of imagination, as Kagan says actually in his ultimate chapter: people didn't understand, didn't see clearly, didn't have the imagination to see the likely consequences of the steps they took — produced a war which they didn't have to fight.

One of the really important conclusions Kagan reaches is that Athens really wasn't threatening Sparta's position — that Pericles, the great leader of Athens at the time, did accept the basic deal which had been done between Athens and Sparta at the end of an earlier confrontation, what's called the First Peloponnesian War. And so Athens wasn't really threatening Sparta at all, and the Spartans probably kind of understood this, but somehow things got out of hand.

And of course, when you tell the story like that, it feels very familiar. And feels very frightening. Because it does seem to offer, from 2,500 years ago in an unimaginably different social and political and geographic and military and technological setting, a set of propositions which are scarily resonant to our present predicament.

WALKER: Right.

WHITE: If you study the plays, the great plays, or you study the great philosophers, the dialogues of Plato, the Socratic works and so on. You can't help but not just be familiar with it, but in a way to love it.

And so the sense of fifth century Athens, this was one of the most amazing moments in history.

And yet they couldn't avoid these screw-ups. The same community that could produce Sophocles and Euripides and Socrates and Plato could produce these mistakes.

That's a warning.

WALKER: [laughs] So many analogies to be drawn. I mean, obviously you can think of Epidamnus as like Taiwan, but...

WHITE: Yes.

WALKER: ... plenty of analogies to World War I as well.

WHITE: Absolutely. I mean, Epidamnus is Taiwan or it's Serbia. Or it's the assassination of the Archduke.

And the analogy there is in many ways quite precise. And this is the point about the Thucydidean distinction between ultimate and proximate causes.

If we look at the origins of the First World War — I guess we'll come to that — all sorts of stuff was happening, centuries long, decades long, fundamental transformations in the nature of the international order or at least the underpinning distribution of wealth and power.

But then a whole lot of little things happened, and in some ways the analogy with the assassination of the Archduke in 1914 is not so much with Epidamnus because that happened a few years before. That's more like the Moroccan crisis, for example.

Or the Balkan crises of 1909 and 1911. All sorts of bad things happened in which bad choices were made and then finally one happens which sets the whole thing off. That might be the Megarian decree.

WALKER: Exactly.

WHITE: That's the last thing [where] you say, "Why did they do that?"

WALKER: So there's this city in the middle of Attica, Megara. I think it's still an occupied city.

WHITE: Oh yes.

WALKER: And Pericles issued a decree. I think the pretext was that the Megarians had violated some sacred land and killed the Athenian diplomat who went in the aftermath of that, and also given safe haven to some Athenian slaves, who fled Athens. But probably the real reason was to punish them for their involvement in the Epidamnian affair.

WHITE: Yes.

WALKER: And it was essentially one of the first instances of economic warfare, right?

WHITE: What they did was slap trade sanctions on them. Sound familiar?

WALKER: Exactly. And this was obviously an ally of the Spartans.

WHITE: Yes.

WALKER: Thucydides de-emphasises the role of that event in his account, but Kagan kind of elevates it again.

WHITE: Re-elevates it.

WALKER: Let me tell you what I didn't like about this book. And then I want your feedback. So Kagan disagrees, obviously, with Thucydides that war was inevitable, however we want to interpret that word.

WHITE: Yes. And whether Thucydides really thought that.

WALKER: Exactly. Kagan seems to just take the literal interpretation of inevitable.

WHITE: I think for the purposes of the exercise, he takes that as his starting point.

WALKER: Sure.

WHITE: I think a classicist of Kagan's sophistication would probably understand— and just to be clear, I'm no scholar of ancient Greek, but I understand that the word which is usually translated as inevitable means something more like "very bloody likely".

And that's different. Inevitable is a very strong word to use.

WALKER: That's a strong word.

WHITE: And people use it all the time. And so I think, in a sense, he's taking that traditional translation of Thucydides as a way of setting up the argument, because, of course, Kagan, in a sense, is no more interested in what happened in fifth century Attic Greece than we are. He's writing this at the height of the Cold War.

And he's very engaged… Hee becomes an active participant in contemporary debates. He became a leading Neocon after the end of the Cold War. His sons, one of them in particular, Bobby Kagan, to whom this book is dedicated, became one of the principal advocates of the Iraq invasion, for example. And there's a very poignant passage in the book early on when he discusses the Athenian attack on Egypt, which is one of the contributing… a completely unnecessary stupid attack on Egypt, which has some resonances with the American invasion of Iraq.

But Kagan was deeply interested in contemporary strategic affairs. And in the end, I think he's choosing to take Thucydides' proposition about inevitability as a starting point for a conversation about how wars happen.

And so I think if you actually quizzed him as a linguist of ancient Greek, he'd acknowledge that “inevitable” is not the best translation of that formulation.

But it's a good way— it's a great way — of setting up the argument.

WALKER: Yeah. And Thucydides probably was being hyperbolic, if he was using it in the literal sense.

WHITE: Well, put it this way, I've always thought he was far too good a historian and far too good a strategist to make the mistake of imagining that anything in human affairs is inevitable.

There are always choices.

And in a sense, the great drama of this whole subject — and it's worth making the point, I guess — the subject is how do countries find themselves going to war? Particularly, how do they find themselves going to war in really big wars against really formidable opponents? Deciding to go to war against weak countries is easy — not very nice, but it's easy. Deciding to go to war against a major adversary is a very big step indeed. And so the question is, how do countries reach this kind of decision? And I think Kagan is setting out to really interrogate that question. And it’s a very important question.

WALKER: Let me tell you, though, what I didn't like about it. So, let's take inevitable as just meaning very bloody likely. Kagan says that there were pre-existing conditions that made the war possible or narrowed the choices of statesmen, but it was this sort of concatenation of mistakes and errors of judgment by statesmen, on all sides, who lacked imagination, that caused the war to start — that provided the spark.

And we've already touched on some of them, but just to list some of those mistakes: I think he places the most blame at the feet of the Corinthians for getting involved in the Epidamnian affair. And their miscalculation was not thinking that the Athenians would get involved.

And essentially, they wanted to mete out revenge on the Corcyrians.

WHITE: Corcyrians, that's right.

WALKER: So Corinth was the mother colony of Corcyria. Corcyria was the mother colony of Epidamnus. An incredibly incestuous kind of quarrel. [laughs]

WHITE: [laughs] And you've got to remember, all of this is happening with a total population of a few hundred thousand. I mean, everybody knows everybody.

WALKER: It’s a small world.

WHITE: It's like Canberra. [laughs]

WALKER: [laughs] And no less bloody, in the end.

WHITE: [laughs] No less bloody.

WALKER: So the Corinthians miscalculate. The Athenians get involved. Then the Athenians really make two mistakes. One is the Potidaean Affair.

So this is now in, I guess, Macedonia.

WHITE: Yes. It's up the top right-hand corner, so to speak, of Greece.

WALKER: Another Corinthian colony.

WHITE: That's right.

WALKER: Athens issues an ultimatum to them.

And then there's the Megarian Decree.

So those are two errors of judgment on the part of Pericles that antagonise the Spartans.

You also have mistakes on the Spartan side. There's a hawkish party in Sparta who's agitating for war. And the Spartans, right up until the last moment, they don't have to tip this thing over into war.

WHITE: And although — and Kagan describes this very well — people's image of Sparta is that they're all sort of crazy militarists, in fact it was a much more sophisticated, complex, weird society than that.

And there was certainly a hawkish faction. But there were also very significant elements of the Spartan polity that thought that getting on with Athens was going to be just fine. And that's one of the reasons why it took a while for the war to break out, and it took all these incidents. The whole stuff with the Corinthians and the Corcyraeans and Epidamnians, as you said. But also the Potidaean crisis and the Megarian crisis.

It took all of that adding up to finally reach the point where the Spartans said, "Bloody hell, all right. Off we go."

And of course once the war begins, then of course the whole dynamic changes and the prosecution of the war itself becomes an end in itself. And then people get killed.

WALKER: And you start to hate each other.

WHITE: And you end up with the dreadful sunk costs fallacy, so eloquently expressed by Lincoln at Gettysburg, that these honored dead shall not have died in vain.

But the fact is they were already dead.

I think what I like about Kagan is I think he does do justice to the complexity of the process. People often, looking back, think wars break out for simple reasons.

Whereas there are a lot of different strands, even leaving aside the ultimate causes, if you just look at the proximate causes, a lot of different strands are coming together to produce a situation where political leaders, national leaders, end up deciding that going to war is a better idea than not going to war.

Which in the end is what it always ends up being: that choice. Is it better or worse? Are the costs and risks of war better than the costs and risks of avoiding war?

WALKER: Okay, but now we've set up Kagan's view, here's what I didn't like about it. And apologies if this is being unfair to Kagan, but this is how I read him.

The problem I have with arguments of the form, “the war wasn't inevitable because we can imagine a counterfactual where these precipitating events didn't happen…” So he goes through those mistakes and says, “you know, it could have gone either way, other choices were available,” and then comes to the conclusion that war wasn't inevitable.

The problem I have with arguments of that form is that, in those universes where those mistakes weren't made, other mistakes can be made later. So really it shows that war wasn't inevitable in 431 BC, but it doesn't show that war wasn't inevitable at some point in the second half of the fifth century BC.

WHITE: Yes. That's a fair observation, but the fact is that at every point leaders, people, have choices. And at every point it's open to people to make a choice between peace and war.

And I think it is true that at every point it's not inevitable, it's not true that the only choice people have is to go to war.

People often say in connection, for example, with the non-hypothetical question as to whether Australia would support the United States and go to war against China if China attacks Taiwan… People in this town [Canberra] often say, “We would have no choice.”

That is wrong. We would have a choice. Now there would be costs for the choice not to go to war in support of the United States. But we could choose to accept those costs rather than choose to accept the costs of war.

And being very self-conscious, very reflective, very analytical, very cautious and prudent about how you weigh the costs of one side against the costs of the other. Making yourself very aware of those choices that you're making, seems to me to be a terribly important piece of policy.

So I would defend Kagan's interpretation, because even if a different set of circumstances had arisen; even if the Corinthians hadn't misjudged Athens' support for Corcyra; even if Pericles hadn't gone in so hard against the poor old Potidaeans and not torn their wall down and one thing or another; even if he hadn't got vindictive towards the Megarians; or even if the, so to speak, peace faction in Sparta had been more powerful and the hawkish faction had been weaker; and so even if war had not broken out when it did, then the next time a similar set of circumstances arose, and they almost certainly would have, then the Athenians, the Spartans, everybody else involved still would have had choices, and they still could have chosen not to.

And I think to ever surrender to the thought that under whatever circumstances, war is inevitable, is to let ourselves off the hook, to relieve ourselves of the responsibility for the choices we make, and putting our choices back into the middle. Our choices, our leaders' choices, but in the end, our society's choices — putting our choices back into the middle of the mix. Asking ourselves, “Do we really want to choose this?” Do we really think that going to war with Athens is a better idea than making some compromises, accepting what's gone on, accepting that they've screwed over the Megarians in a vindictive and, frankly, unjustified — from the benefit of a lot of hindsight, what Athens did towards Potidaea and what they did to the Megarians looks unjustified. But the Spartans could have chosen to say, “Okay, you know…”

Now of course, when we view that at this point in history, in hindsight, looking back at what happened in 1938 and 1939, we think that answer is easy. We think that we have no choice. The Munich metaphor — we'll probably come back to that.

I think it's very important to preserve our consciousness of the fact that we do have choices to make, and I think that's what Kagan — because he does it so exhaustively and unpacks all of those choices at such length — does it very compellingly.

And I've always, when I find myself thinking about the choices that I think Australia and America and other countries face as they confront the rising power of China and the fear that causes, then I find myself often going back to Kagan as the kind of way into the great Thucydidean debate.

WALKER: Next book?

WHITE: Next book.

Garrett Mattingly: The Defeat of the Spanish Armada [29:03]

WALKER: Alright.

So, the next book is The Defeat of the Spanish Armada by Garrett Mattingly. This was first published in 1959. Mattingly was an American historian, professor of European history at Columbia, and he specialised in modern diplomatic history.

This is a narrative history. You might describe it as purple prose, but it's incredibly enjoyable.

WHITE: Oh, yes.

WALKER: Won a Pulitzer, I think.

WHITE: Yes, I think it did.

WALKER: And it, of course, describes the defeat of the Spanish Armada by the English in 1588, and the backdrop to that event.

So, why this book? Why is this on the list?

WHITE: Well, partly, in a sense, sentimentally. I read it as quite a young man — probably I was still at school — because my father recommended it to me. And my father was in the trade. He was a defence official. And my own interest in this whole business does owe something to the fact that I sort of grew up with it a bit. And it was a very uncharacteristic book for my father to recommend because, as you say, its prose at points is quite purple. It's a very colourful narrative.

And [my father] was an engineer with, if I can put it this way, an engineer's soul. He used to say the best way to improve a piece of writing is to cross out all the adjectives. Which is sort of what he did.

Whereas Mattingly sticks plenty of adjectives in.

WALKER: And adverbs. [laughs]

WHITE: Yeah, and a lot of adverbs.

But it really made a big impression on me, partly because of the way in which it illustrates how many different strands there are that feed into this.

Unlike Kagan, it's not about the… Well, it is, of course, about the individual decisions people take. But one of the things it's about is how many different players are involved. And it's also — and this is a recurring theme, we touched on in Kagan, about Kagan's point about failure of imagination — the mistakes that people made. In this case, particularly the mistake that Philip II, the King of Spain, made in launching the Armada to start with.

But one of the things that's fascinating about it, it starts with the execution of Mary, Queen of Scots at Fotheringay. Which, until I read it, I had never recognized that that was, in terms of proximate causes — there was the grand sort of growth of Spanish power and the way in which Spain… And of course a whole religious dynamic, the Reformation versus the Counter-Reformation — there were very big forces at work there. But the execution of Mary, Queen of Scots was the beginning of the proximate causes.

WALKER: And she was, of course, Catholic.

WHITE: And she was Catholic.

WALKER: And he wanted her on the throne.

WHITE: That's exactly right.

The thought that she might, if Elizabeth died — Elizabeth I, Queen of England — if she had died, Mary would have taken the throne, England would have returned to its Catholicism, and Spain would have gained an adherent and been spared a country that was becoming a more formidable adversary.

So, there was both religion and real power politics involved, and one of the things that makes the whole era fascinating is the interconnection between them.

But then, there's this whole business of what's happening in France, where there's this very bitter civil war between, broadly speaking, Catholics and Protestants. But also, between supporters of Spain on the one hand, and a whole range of others on the other.

And one of the things that's fascinating about the book is the way in which Mattingly interweaves the struggle in France, which turns out to be vital; Elizabeth's own thinking in England, because she's very, very reluctant to make an enemy of Spain, but in the end, not that reluctant (her decision-making, the description of her decision-making about the execution of Mary, Queen of Scots itself is worth the price of the book); and the way in which decisions are made in Rome, by the Pope; by Philip II, immured in his weird, isolated castle fortress monastery, the Escorial in the hills outside Madrid...

WALKER: It’s this sort of nerve centre of the [empire]. And he's just there, sort of, sending out letters across the empire.

The Spanish Empire, it's the first empire on which the sun doesn't set.

WHITE: The first global empire. That's exactly right.

WALKER: And he's sort of from this nerve centre, just sending letters and correspondences out. Calling the shots.

And he seems very isolated.

WHITE: Oh, he is. That's right. He's an extraordinary bureaucrat in a way, Philip II, a fascinating character. He was a workaholic, and he wrote everything down.

I think Mattingly mentions it in that book. If not, it's in another book by a bloke called Geoffrey Parker, called, I think, [The Grand Strategy of Philip II]. At any rate, he wrote all this stuff in the margins.

At one point, he writes in connection with this, “I don't understand what this person means. This is very confusing. What am I meant to think about this?”

WALKER: And one of his generals or admirals is saying that it's going to be easy to defeat the English fleet in the channel.

WHITE: Yes.

WALKER: And he writes, “Nonsense,” or something.

WHITE: Exactly.

And so, you get this wonderfully vivid sense of this person across the centuries. And in some ways, Philip II, heir to the unimaginable Habsburg Empire, son of Charles, probably the greatest hegemon Europe has ever seen, at least before Napoleon (but Charles’ hegemony was more lasting). An extraordinarily remote character, but it feels very vivid, this man, this individual, making these decisions — and in the end, although he was a very prudent person, getting it wrong.

And Mattingly describes how he, pushed by events, pushed by the Pope, pushed by his own diplomatic representatives in France who saw the Armada as a way of prosecuting Spain's agenda in France as well — and in the Low Countries, because the Spanish response to the rebellion of the Protestants in the Low Countries, what's now Holland and Belgium, was central to all of this — he comes up with this harebrained scheme.

Militarily, this is a harebrained scheme. It requires one fleet to sail from Spain up the Channel. And then somehow, his commander in the Low Countries, to ship a huge army across the English Channel. This is heavy stuff. [laughs]

And one of the reasons why it's so enthralling is that the book is a very good example of the way in which all of the stuff we've been talking about so far — grand changes in the distribution of power, the way in which statesmen respond to individual events, all of this sort of stuff — that's all one thing. On the other hand, it's the sheer military reality of this stuff.

There are two bits of it that come across here. The first is how hard it is to move soldiers across water. The fact that England is an island makes all the difference. And Philip has this very strong army in the Low Countries, in the Netherlands essentially, which he hopes to ship across the English Channel. And the Armada is really there to win control of the channel, to give that army a chance to get across into England. But it just turns out to be really hard — assembling enough boats turns out to be really hard.

And the other thing is that, as it happens, when technology comes into play, the English guns were just much better than the Spanish. And so, it's a purely technological thing. The English had smaller ships, but better guns. And they could stand off and inflict real damage on the Spanish ships without getting close enough to grapple.

Whereas the Spanish style of naval warfare was to get so close that you actually grapple onto the ships and the soldiers who are on your ships jumped onto the other guy's ships. Well, if the other guy's guns were better at longer range, you couldn't make that work.

Now, a lot of other things were involved in the outcome of the Armada, including the weather, which always counts for something, particularly in the age of sail. But when you look at Philip's decision, sitting alone there in the middle of the night in the Escorial, a big factor… And of course, they knew that: they'd been fighting the English; they knew what they were up against.

It's hard now... And Mattingly makes the point really, or at least the point comes through from his wonderful, colourful description of what was going on: “Why did Philip do this? This was a dumb decision.”

And, well, the study of dumb decisions is pretty much the study of how wars happen.

WALKER: [laughs] Was the religious motivation, restoring the status of Catholics in England, just a pretext?

WHITE: I don't think it's just a pretext. I mean, it's very hard for someone in our secular age, and certainly someone of my totally secular disposition, to think my way into the state of mind of a devout Catholic in the middle of the 16th century, with this extraordinary challenge from the Reformation. And the way in which people's view of human life was built around their sense of religion, the place of Catholicism in Europe's sense of itself, and the idea that this would be violated by the Reformation, I think it's very hard for us to recreate what that meant.

So I don't think it was just a pretext. I think it was for real and to a certain extent you can see that from what individuals did, not just Philip himself, but the martyrs going to the stake.

I studied for a while at Oxford, and just outside my college, there was a cross in the road, in the street, where the Oxford martyrs had been burnt at the stake, just before this, when Queen Mary, before Elizabeth, was [queen]. And just walking past it, as I did every day, it just gives you a sense: it really meant something to people.

So I don't think it was just a pretext. On the other hand, it didn't run counter to Spain's strategic interests and to the Habsburg's strategic interest. It directly reinforced it. Bringing England back to the Catholic faith brought England on Spain's side against its various adversaries, including, of course, against France.

Now, where France was going was itself a huge issue, and in a sense, the whole Spanish Armada story — and this is one of the points that Mattingly makes — was a kind of subset of a big story about the contest between Spain and France. Which is hard for us to get our head around now because we're used to Spain being, at best, a second-order power but, of course, in the 16th century, it was absolutely a first-order power.

WALKER: Next book?

WHITE: Next book.

WALKER: Okay.

WHITE: But also, I mean, the thing about Mattingly: as a story, I just find it riveting. I go back and re-read it every few years just for the pleasure of it.

WALKER: The chapters are pretty short, and some of them are just gorgeous.

WHITE: Oh, yes.

WALKER: They're like paintings or scenes.

WHITE: Oh, that's exactly right. And moving too.

There's a description which seems in some ways to be obiter dicta, but the description of a battle between the Protestant and Catholic side in France within the French Civil War, which is one of the best descriptions of a battle I've ever read.

WALKER: Really?

WHITE: Yeah.

WALKER: Why so?

WHITE: It's just so vivid and concise.

He sets up — and I'm not really a military history buff, I should say — but he sets up the geography of the battle with the Protestants on the defensive in a fork between two rivers and the Catholic Royalists across the arc between them.

And the sense of how the Catholics, supremely confident of victory and they're fresh in the field… The Protestants have been campaigning all year; they're feeling weakened and demoralised. But in the end, they win. And how that unfolds…

WALKER: Do you remember which chapter?

WHITE: Oh, yes. I can find it for you very easily. 'The Happy Day', 136.

WALKER: Is it too long to quote?

WHITE: Yes, it's too long, I think. But…

“Across the few hundred yards of open ground, the opposing horsemen had time to eye each other. The Huguenots looked plain and battle-worn, in stained and greasy leather and dull grey steel. Their armour was only cuirass and morion, their arms mostly just broadsword and pistol. Legend was to depict Henry of Navarre as—” He was their leader. “—as wearing into this battle a long white plume and romantic trappings, but Agrippa d'Aubigné, who rode not far from Navarre's bridle-hand that day, remembered the King as dressed and armed just like the old comrades around him. Quietly, the Huguenots set their horses, each compact squadron as still and steady as a rock.” Et cetera.

“Opposite it the line of the royalists rippled and shimmered.”

WALKER: That's so good.

WHITE: He could really write, this bloke.

WALKER: He could.

WALKER: No offense, but a little bit surprising. I mean, this guy is a historian, and he just comes out with... He's a serious scholar. And then he comes out with [this].

WHITE: Oh, he's a serious scholar. And, for example, he wrote a book called Renaissance Diplomacy, which is full of vivid little vignettes, but it's a very serious, dry, sober piece of history.

As I said, I was first introduced to Mattingly with that book by my father. And when I saw that he'd written this thing, Renaissance Diplomacy, I thought, "Oh, that'll be great."

It's actually very interesting. But it's a bit dull. [laughs]

A. J. P. Taylor: The Struggle for Mastery in Europe, 1848-1918 [47:08]

WALKER: Okay, next book, The Struggle for Mastery in Europe, 1848-1918.

WHITE: Ah, yes.

WALKER: So this was first published in 1954. The author is Alan John Perceval Taylor, A. J. P. Taylor: eminent English historian who specialised in 19th and 20th century European diplomacy.

So this book is a diplomatic history of the struggle between Europe's great powers from the democratic revolutions of 1848 to the end of the First World War. It's a river of facts, characters, events, flowing from '48 to 1918.

And an interesting fact about this book: Taylor knew German, French, and a little Italian, and obviously English, and he learned Russian in the course of writing this book, reading the diplomatic archives, because he thought it would be useful.

He started writing it in 1941, during the Second World War, interrupted it to complete The Course of German History, one of his other books, which was published in '45. And so he came back to this and finished it in 1953. So for more than a decade, he was working at this book.

WHITE: And what a decade.

WALKER: What a decade.

It is sweeping. There were two chapters in particular that you recommended to me: Chapter 18 and Chapter 22.

So Chapter 18 is about the making of the Anglo-French entente in the early 1900s. What's significant about that for you?

WHITE: It's worth stepping back a bit. Why is the book on my list?

WALKER: Yes, okay.

WHITE: There are two reasons for that. The first is because it is a textbook as to how the European order worked in the 19th century, at least in the second half of the 19th century. And in particular how the European order adjusted to the phenomenal shifts in the distribution of wealth and power that occurred over that time.

Germany in 1848 is — I forget the number: 37? 137? — anyway, some bizarre number of different sovereignties. Germany as we know it didn't exist.

WALKER: Little states, lots of little states.

WHITE: Little states. Well, some of them—

WALKER: Prussia's big. Austria's big.

WHITE: Prussia's big. Austria's big, of course. Some of the others are reasonably large. And Prussia is kind of a great power. No, Prussia is a great power, but it's a marginal great power. And there are all these other states. So Bismarck has not begun his process of creating modern Germany.

And, of course, Russia is still completely backward. Russia is nowhere.

The Ottoman Empire is still a fairly serious proposition and so on.

And so, the distribution of wealth and power, the underlying international structures, which created 1914 were still then a long way off. And yet the European order survived and flourished over those years from — not until 1918 [laughs] — until 1914.

So it's a textbook for how a very complex multipolar order in an extraordinarily dynamic era… I mean, we think we're living through an era of change, but you think of the changes that occurred in Europe. I mean, apart from anything else, just off the top of your head: railways appeared. I mean, boy, talk about change. Steam navigation appeared. Globalisation. Well, globalisation had begun before, but this was the full fruits of the Industrial Revolution transforming the way people lived, states worked, the whole thing.

And so it's a textbook for the way in which — as you say, an extraordinarily detailed textbook — Europe managed this process. And that seems to me to be inherently very interesting. That's the first reason.

The second reason, it's AJP Taylor. Which means it is full of the most outrageous statements. He'll generalise: you know, boom, poof.

But always insightful. Always stimulating. I just love his prose.

WALKER: He's always taking a few potshots at people.

WHITE: Oh, he takes potshots at people, and he'll just say, “That's complete rubbish. It was this [or that] —”

And sometimes one will disagree. But most of the time, you just, so to speak, savour the texture. I mean, it's a little bit like reading Gibbon.

Perhaps I shouldn't admit this: I do sometimes in moments of stress or relaxation just pull my copy off the shelf and open it and read it at random just because I love the way the prose works. I do the same with Gibbon actually, every so often. Gibbon can be describing some completely nonsensical theological dispute in the Middle East sometime in the seventh century, but somehow the prose will just carry you along for a few pages and make the world seem a better place. And that's Taylor for me. So, that's the broad setting.

But if we look at Chapter 18, for example, two things are happening at that moment — and this is the 1890s, roughly speaking. The first is that — and it's sort of hard to remember, but particularly under the Second Empire, under the second Napoleon, the first one's nephew — France still looked like a very threatening place to Britain. And because we know how the story ends, including, of course, France's defeat by Germany in 1871… But to the British, France still loomed very large.

So, one of the great revolutions, one of the great ways in which that order, as I mentioned before, adapted to what was going on in Europe, was the long process of rapprochement between France and Britain, which came to a head at that time. And I loved the description he gives of the way in which that happened.

But that's not the only thing he's talking about. Because he also in that chapter is talking about the way in which issues outside Europe — because this is the high point of European colonialism, and Europe is perhaps, in a sense, the strongest sense we've ever seen before or since, ruling the world... European colonialism had gone through an extraordinary explosion in precisely the period covered by the book. And so, he's describing the way in which events outside Europe, particularly in this case, in the Far East, as they called it — China — start to really hone in on what's happening within Europe.

And so, that sense, particularly for an Australian reader, in which what's happening in the Far East, particularly what's happening with China — which is always a big part of my interest in whatever's going on — is impinging back into Europe and creating the circumstances which, amongst other things, led to the Pacific War... I mean, there's a lot of water [that] goes under the bridge before that happens, but you can see the questions about Japan's place in Asia, the question about Japan's relationship with China, the question about Japan's relationships to the Europeans, and the Americans’ (we'll come back to that) relationship with China. You can see them all starting to bubble to the surface there.

The whole book in a sense can be seen — I think should be seen — as a long exposition in extraordinary detail of how we ended up in 1914 on the 4th of August.

But it's a bit more than that. It tells you a lot about how the modern world was brought into being by what happened in the latter half of the 19th century, which is a big part of the prologue to what we've lived through in the 20th century and what we're trying to deal with now.

WALKER: I think worth emphasising: it's fundamentally a diplomatic history. So, it's not a general history.

WHITE: No.

WALKER: It's sort of lacking the economic and military dimensions.

WHITE: Yeah. It's a history of diplomacy and strategy. The military is never far below the surface.

WALKER: Right. So the kind of documents he's reading are sort of memorandums of foreign offices.

WHITE: That's right, yes.

WALKER: Minutes. Correspondences between foreign ministers and their diplomats and ambassadors.

WHITE: Yes. That's that. And so, it's a classic old-style diplomatic history of the sort which is, I guess, in some ways discredited these days, I think wrongly; I think there's a great deal to be learned from that kind of thing. Because in the end, these might not be people or attitudes that are broadly representative of society. But they're the people and the attitudes that are in the room when wars are decided on. So pay attention.

WALKER: Yeah. So, Chapter 22 is on the build up and then outbreak of the First World War.

WHITE: Yeah. Brings it right down to the moment.

WALKER: Exquisite chapter.

WHITE: Yeah.

WALKER: I've got about three pages of notes on it.

WHITE: Yes [laughs].

WALKER: But I'm curious what you took from that chapter, if you can distill it.

WHITE: Look, it's a little bit hard to separate that from the whole question about what happened at the beginning, what happened from the 28th of June to the 4th of August, 1914.

But one of the things, one of the really critical questions about that moment is: how far did the various participants intend? Who intended to go to war? In particular, did Germany want to go to war? There's a strong argument, particularly in Germany itself after the Second World War, there's a strong school of thinking that the Germans really planned the war.

What on earth were the Austrians thinking? Why did they think it was so necessary to go to war with Serbia given that there was a threat that Russia would intervene and so on? And the French and the British.

What I really take from it is, first of all, because that chapter has its roots in all the previous chapters and therefore connects what happened in those weeks from the 28th of June to the 4th of August, with all that had gone before, back to 1848, I think it makes it very powerful. But he also has some really important propositions.

He gives a very compelling argument that the Germans had — you've got to be very careful of the collective nouns here, because one of the things about what happened in those weeks is that in Germany, in Austria (Austro-Hungarian Empire), and in Russia, and to some extent in France, the decision-making was very fractured.

I mean, in the first three, in all three, you had these weird — these were modern states with modern economies, this is a world we can kind of relate to when we look at it economically — but they're still governed by these absolute monarchs.

WALKER: The Kaiser is really the commander-in-chief.

WHITE: Yeah. And he's mad as a meat axe.

The Tsar, even more than the Kaiser. I mean, the Kaiser at least has to deal with the Parliament; but in St Petersburg, the Tsar really is the boss.

But he's completely ill-equipped to perform this function. And Franz Josef in Vienna, the head of this weird polyglot empire, which hardly makes any sense at all...

And not just in Taylor; I mean, there are whole books, some very good books, written about what happened in those few weeks. But one of the things that comes clear, and Taylor touches on this, is how confused the decision-making is because the structures are so poor.

And in some ways, the only one of those capitals in which you get a sort of a halfway sensible analysis of the choices is in London (and [inaudible] is a tale in itself).

So one of the things I really like about Taylor's account is that he does a very good and actually quite concise job of adjudicating the question as to whether the Germans wanted to go to war or just went along with going to war. And there was certainly a strand of German thinking that said, "We're going to have to fight eventually." And particularly their fear of Russia.

I think in our present understanding, we underestimate the extent to which the real rising power in 1914 was not Germany but Russia.

Russia was coming out of nowhere and industrialising really fast. And so it's traditional… It had always had a place. Well, not always. Since the days of Peter the Great at the beginning of the 17th century, Russia had been a significant player in European power politics.

But as Russia was changing, it was industrialising, it was going through its industrial revolution, two generations, behind the rest of Europe. But because of its sheer scale, that made it very impressive.

And so the combination of that, the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, and all the vulnerabilities, the obvious weakness of Austria, the Germans had reason to think it might be better, if you're going to fight, to fight now than later. But I think A. J. P. Taylor's adjudication of that question is very good.

WALKER: Yes.

WHITE: The other thing I really like about the chapter is the way in which he analyses the British decision-making.

Because there's an argument which he addresses directly, if I remember rightly, that if Britain had only said right at the beginning that it was going to fight or not going to fight—

WALKER: If it had been unequivocal.

WHITE: Unequivocal one way or the other, then it would either have deterred the Germans or deterred the French and the war wouldn't have happened.

And I think he destroys that.

WALKER: Rejects that.

WHITE: Rejects and destroys it very, very compellingly.

WALKER: Right. So he says it was essential to the Schlieffen Plan that the Germans had to violate Belgium.

WHITE: Yeah. They were going to go through Belgium whatever happened.

WALKER: They were going to go through Belgium, and they'd already factored in that if they violated Belgium's sovereignty, then the English would intervene.

WHITE: Then the British would be in.

WALKER: And they discounted Britain's involvement. They didn't think it was going to affect the outcome one way or the other.

WHITE: Which was a not unreasonable position for them to take.

WALKER: Because Britain would only submit a couple of divisions.

WHITE: Six divisions.

WALKER: Six divisions.

WHITE: Well, five initially.

WALKER: And so maybe one division is like 15 to 20,000 troops.

WHITE: That's right. And, you know, by comparison, the French and the Germans both mobilised way over 100 divisions, something like 160 divisions.

WALKER: Over a million troops.

WHITE: The British army weight was really negligible. In the end, actually on the day, it didn't have a negligible impact on the way the battle unfolded in August — we might come back to that. But in the sort of grand strategic weight, Britain really only counted as a maritime power. And its maritime power really only came into play if the war dragged on. And the Germans being confident that the Schlieffen Plan would work, that they'll be able to knock France out in six weeks and then turn on Russia, knock Russia out…

So the idea that Britain's commitment one way or the other would have made a big difference to German thinking, Taylor demolishes in a few sentences. And I think quite correctly. I think it's a very compelling argument.

Of course, you can make the same point the other way. If they'd said to the French, "We're not going to fight," then the French wouldn't have fought? No. No, apart from their alliance with Russia, which was really fundamental, and particularly the attitude of Poincaré...

I think you can argue that the only one of the European leaders who, in those last days of July and first days of August, really wanted the war to happen was the French President, Poincaré.

That's not a common view, I might say, but back in 2014, like a lot of other people, I found myself reading a lot of books about what happened a hundred years before. And my conclusion was that of all of them, he was the one who was least ambivalent.

The rest of the French government wasn't. But as president — and he was very influential partly because the rest of the government was in chaos because this is what French governments in [laughs] the Second Empire were like — he was very influential.

So, I think Taylor is right on that as well.

WALKER: I want to compare a couple of my notes with you, but could you give a 30-second description of the Schlieffen Plan just for anyone lacking that context?

WHITE: Sure. So Germany's problem as it saw itself in a traditional rivalry with France, very strongly amplified, of course, by the outcome of the Franco-Prussian War in 1871 in which the Germans marched off with two key French provinces, Alsace and Lorraine.

On the one hand, France on one side, Russia on the other — this rising Russia — who had allied themselves with one another to neutralise or at least to manage Germany's rising power. So, Germany's problem in the event of a European war was that it faced the potential for war on two fronts. And in order to manage that problem, Schlieffen, who had been their overall commander in the late 19th and very early 20th century, formulated a plan in which Germany would defeat France in six weeks, and then swing all its forces against Russia.

And the way to defeat France, given that the French had very strongly fortified the border in the middle part of the border, was to go through Belgium. A huge army swinging through Belgium and then swinging around to hook behind Paris and then drive the French forces, enfold the French forces in a giant encirclement.

And it involved the violation of Belgium. And Belgium, when it was established as an independent state in the 1830s, was neutral, and its neutrality was guaranteed by all of the key European powers including Germany. And this therefore involved the violation of what was seen as a really fundamental principle of European order.

So the German war plan, if they were going to go to war with Russia, they had to go to war with France, and if they were going to go to war with France, they had to invade Belgium.

WALKER: Because of the entente between…

WHITE: Well, the problem was they couldn't go to war with Russia without assuming that France would go to war with them because they knew that that's what France's commitment to Russia entailed.

WALKER: Yes.

WHITE: And this was not a wishy-washy alliance. It had a lot of substance to it.

It wasn't as substantial as NATO, where NATO kind of distorts our view of the way alliances work. But the French had, for example, poured, in contemporary terms, billions of dollars into helping the Russians build the railways that would ship Russian troops to the front against Germany. So, this was not just a piece of paper. This was very practical, strategic cooperation.

And as it happened, Poincaré, as president of France, visited Russia at the end of July. He had just left Russia on his yacht.

WALKER: Yeah, him and Viviani were on their way back when-

WHITE: Exactly, and with his [prime] minister, Viviani. The Austrians delayed the issuing of their ultimatum to Serbia—

WALKER: Until they were at sea.

WHITE: Until they were at sea. You know?

WALKER: Yeah.

WHITE: Like I say, the people in the room, you know?

WALKER: That's right. So on the Schlieffen Plan, Germany knew that if it was to fight either France or Russia, then it had to fight both.

WHITE: Had to fight both. Yeah.

WALKER: To avoid fighting a two-front war — and there was this cult of the offensive at the time — but the decision was just to overwhelm France.

WHITE: Yeah.

WALKER: Why France, not Russia? A large part of the logic was it would take Russia much longer, like several weeks, to mobilise because of their disorganisation, and also just the—

WHITE: The sheer distance.

WALKER: The sheer distance.

WHITE: The sheer scale, that's right.

WALKER: So we'll overwhelm France first, and then we'll swing back towards the eastern front.

WHITE: And it’s partly just a matter of distances on the German side as well. I mean, in order to achieve a decisive result in Russia, you had to travel a long way, as people keep on discovering. You know, Napoleon and Hitler and so on.

Whereas France is relatively compact. You know, you could get from the German border to Paris in a few days.

And so inherently it was a quicker war to fight because the distances were not as great.

The German troops as they came down, you know, they came through Belgium and then headed south down towards Paris, and at the last moment, so to speak, they swerved to the east, to the left of Paris, viewing it from their line of march. But at the closest point, those German troops could see the Eiffel Tower. They could see Paris in the distance.

But they swerved away for reasons which one of our other books [The Guns of August] goes into at great length, and produced the debacle which produced the Battle of Marne, which produced the Western Front that we all know about. And that claimed so many Australian lives.

But it nearly worked. That's the story of the Schlieffen Plan.

WALKER: Yes. A couple of the notes I had. If you wanted to boil down Taylor's account of the First World War into a sentence or two, it would be that Austria-Hungary, specifically Austria, wanted the war.

WHITE: Yes.

WALKER: They were the declining great power in Europe.

WHITE: Yes, yes.

WALKER: Germany didn't have a plan to start it. He basically says that Bethmann and the Kaiser and von Moltke were just incapable of timing [laughs] the war.

WHITE: Yeah. That’s right [laughs].

WALKER: But when the opportunity presented itself, they went along with it willingly because, for the reasons we've discussed and we'll come back to — but one theme I definitely took from Taylor was that in the background there was this strategic need to fight a preventive war against Russia.

WHITE: Yeah.

WALKER: So Germany went along with it.

Statesmen on all sides succumbed to military timetables and military planning — so these things like the Schlieffen Plan that were already in place that once that process started it was very difficult to stop or reverse it.

WHITE: Yes.

WALKER: And then the Allies fought for defence.

WHITE: That's basically right.

Austria, of course, didn't want the war they ended up fighting. They wanted to fight a war against Serbia.

WALKER: Yes.

WHITE: Their bargain, their gamble, was that they could go to war against Serbia without going to war against Russia, even though Russia had an alliance with Serbia.

It's clear from the archives, in the conversations in Vienna over those weeks, that they believed they could fight a war against Serbia without being attacked by Russia, because Russia would be deterred by the fear of an attack from Germany.

And when the Kaiser, as he did, said to the Austrians after the assassination, "Go ahead and punish Serbia. We'll back you," he probably thought what that meant — well, who knows, because it's the Kaiser — but it's perfectly plausible that what he really thought he was committing himself to was simply standing there to deter Russia, so that Russia wouldn't attack Austria, so Austria could have a war with Serbia by itself.

I think that's basically — although Taylor doesn't put it quite that way — Taylor's argument.

So the question is not just, do you go to war or don't you, but which war do you think you're going to fight?

And often you end up fighting a war contrary to the one you expect.

WALKER: So Germany was egging Austria-Hungary on.

WHITE: Yes and no.

WALKER: Yeah, so it was a little ambiguous as to whether, in Taylor at least, Germany expected that Austria-Hungary would invade Serbia.

WHITE: Yeah.

WALKER: Did they?

WHITE: Well, there was uncertainty, great uncertainty, and there was a lot of uncertainty in Berlin.

Taylor doesn't go into this in that detail because this, in the end, is one chapter in a fat book that covers decades.

But if you look at Albertini's, you know, whatever it is, [three]-volume history of the outbreak of the First World War, which is a sort of bible that everybody goes back to. That was produced between the wars. I haven't read all of it [laughs], but it's a remarkable book.

But, to my mind, the best of the books published in 2014 about what happened in 1914 is a book by a bloke called T.G. Otte called July [Crisis], which unpacks what happened in each capital in great detail.

What's clear from that is that there was a lot of debate in Germany. The Kaiser had given the Austrians the green light, and then sent some flashing amber signals, and then there was another green light from the Kaiser. The messages were very mixed, including messages from the Kaiser himself, quite apart from others.

One of the things that emerges from the detailed study of what happened in July 1914 is that everywhere, but particularly in Berlin, there was a lot of confusion. People weren't quite sure.

And they weren't unaware of the scale of what they were committing themselves to. The Kaiser himself said at some stage in July, quite late in July, that if it comes to war it will destroy European civilisation for a century. Which, for an idiot — which he was — is quite a perceptive observation.

So, the simple-minded version doesn't quite do justice to the complexity. And Taylor doesn't unpick all of that.

For me, the real strength of Taylor, that part of Taylor's thinking, is the way in which you get to it having gone through all of this other stuff about what had happened in Europe.

And one of the points is, we tend to see 1914 as kind of an isolated incident, as if the story begins with the assassination of the Archduke.

WALKER: Oh, no.

WHITE: No, that's the whole point.

I mean, it's ultimate versus proximate causes. All of this has been set up through a century of European history.

And, you know, the way in which things worked through the 19th century, from 1815, the defeat of Napoleon — why did they stop working?

In a sense, one way of interpreting Struggle for Mastery is that it's an account of why what had worked so well stopped working.

WALKER: Yeah. It's notable in both Struggle for Mastery and Guns of August (which we'll come to next) just how little attention is given to the event of the assassination.

WHITE: Oh, yes.

WALKER: In terms of how Germany is thinking about this, the note I had from reading Taylor's chapter is that they're not certain Austria-Hungary will invade Serbia. They're egging them on a bit.

But if Austria-Hungary does attack Serbia, Bethmann Hollweg and Wilhelm II don't expect Russia to defend.

And if Russia does defend, they think, "Well, war's better now than later, when Russia's a stronger power."

WHITE: Yes, that's exactly right. In some ways, the story of what happens in the last week of July is that everybody expects everybody else to let their allies down.

People often say that the cause of the First World War was that they had all these alliances and people stuck with them. But what's striking is that everybody expected them not to stick with them.

The Austrians thought they could attack Serbia without going to war with Russia because they thought the Russians would let the [Serbians] down.

The Russians decided they could go to war with Austria without going to war with Germany because they thought the Germans would let the Austrians down.

[The Germans] also thought there was a fair chance the French would let the Russians down.

But of course, there was a point… Once Germany had built its war plan around the assumption that the Franco-Russian alliance would hold, then it was going to happen.

This gets back to the point you touched on before: a very big factor in 1914 was that once preliminary decisions had been made, it was very hard to turn back.

It was a classic problem — and in fact, it's a very common problem in the management of military operations, even on a much, much smaller scale — that if you want to have a military option, you've got to start taking steps, and once you start taking those steps, you start losing flexibility.

For the Russians, for example, precisely because they were so big and they took so long to mobilise, if they were going to have the option of going to war with Germany, they had to start doing things earlier than they would have wanted to.

WALKER: Because there was a lag of weeks.

WHITE: Because there was a lag of weeks. And the poor old Tsar — and I say that advisedly, because it's hard to look at him; he just looks so sad and helpless in those photographs, and comes across that way in the documents — the poor old Tsar says, you know, "Well, can't we just mobilise against Austria and not mobilise against Germany?"

And his commanders say, "No, we can't do that."

There's a very clear technical reason for this. One of the things that's happened in the 19th century is that the combination of population growth and industrialisation and railways and telegraph massively increased the size of armies, because there were more people around and better social organisation, and massively increased the speed with which they can be moved.

You could bring together these huge mass armies and move them to the front within days. Vast amounts of energy and imagination, and so on, are devoted to perfecting the concentration and deployment of these forces.

But it required… I think Tuchman touches on it. You talk about another railway train going over the key bridges every seven minutes, 24 hours a day, for weeks.

The thing is so detailed and so sophisticated and so complex, you can't change it.

WALKER: Right.

WHITE: So at one point, the Kaiser, right at the last moment — I think on the 1st of August, maybe the 31st of July — says to von Moltke, his commander, "Well, can't we just go to war with Russia and not against France?" Just as the Tsar has said, "Can't we go to war with Austria but not against Germany?"

And in both cases, what the commanders say is, "No, we can't. Because if we do that, the whole plan will fall apart."

WALKER: We lose the optionality.

WHITE: Exactly. It's chaos if you start disrupting the thing. The whole thing falls apart.

People often think, "Well, that's just the fault of the boneheaded military commanders who didn't have any imagination." Actually, they were themselves prisoners of the particular way technology had evolved, which produced these massive armies that had to be moved by railways with great speed, with great precision, which required incredibly elaborate forward planning.

And of course, we face our own version of that today with intercontinental ballistic missiles. Things move very bloody fast.

You can blame the military commanders for an awful lot of what happened between 1914 and 1918, but I don't blame the military commanders for the predicament they found themselves in in the last week of July and the first week of August 1914.

That was something the technology had imposed on them.

WALKER: Just back to Russia quickly.

So Russia wanted to mobilise only against Austria-Hungary, but they weren't capable of that.

WHITE: Well, the Tsar did.

WALKER: The Tsar did. So they had to do a general mobilisation instead. But at that point, their intention or their expectation wasn't to fight a war; it was to raise the bid.

WHITE: Yeah.

WALKER: And Germany asked them to stand down. They didn't, and then…

WHITE: That's right. Everybody, as I said, hopes that they can deter the other guy from fighting. The great attraction of that is that you achieve your objectives without paying the costs of war.

It's worth bearing in mind that everyone is trying to preserve their place in the European order. You have a European order with five great powers that emerges from the end of the Napoleonic Wars. With the emergence of Germany as a unified power, which is a fundamental change, you've still got those five great powers in 1914.

Austria-Hungary is hanging on by the skin of its teeth. And Germany is not even sure itself that it's got the power that it deserves to have. France is fundamentally weakened by demographic problems, some economic problems, some political problems, and so on, and by the fact that it's just losing out in the race with Germany and then with Russia. Britain is having big doubts itself. Britain had been the world's biggest economy forever, but it's been overtaken by America, probably sometime in the 1880s or 1890s.

So everybody is unsure of their position in the international system. When 1914 comes, all see it as a test of their status as a great power in that system, and all hope they can preserve their position without going to war because the other side will back down.

The Austrians hope to preserve their position as a great power by being mean to the Serbians and hope the Russians will back down. The Russians want to preserve their position as a great power, having been humiliated by Austria a few times in the past, by threatening to go to war and hoping that the Austrians will back down, et cetera.

Everybody is trying to strengthen their position as a great power, but none want to go to war to do it. They all hope that they'll strengthen their position by the other side backing down.

Now, just to foreshadow, that's what both America and China think about Taiwan.

China wants to assert its place as a great power in Asia, in the face of America's power, by threatening to go to war with Taiwan and making the Americans back down, therefore proving the Americans are paper tigers.

America wants to preserve its position in the Western Pacific by threatening to go to war with China if China goes to war over Taiwan, and they hope the Chinese will back down.

Neither side wants a war, but both hope to bolster their status or achieve the status they seek by making the other back down.

And that works fine if the other backs down. But, of course, for precisely the reasons we see in 1914, you end up with a war that neither side wants because both hope they can achieve their objectives by making the other side back down.

And both can end up being wrong.

That's really the great story in 1914, which is why it's so resonant for today.

Barbara Tuchman: The Guns of August [1:25:07]

WALKER: So we have one more book, I mean, at least one more, but this is the only other that bears directly on 1914.

So, next book: The Guns of August by Barbara Tuchman, first published in 1962.

Tuchman was an American historian and journalist. She wrote in the genre of popular history, mainly. And this is essentially a military history of the first month of the First World War.

WHITE: Quite right.

WALKER: Brilliantly written, won a Pulitzer. Why is this on your list?

WHITE: For two reasons.

The first is that it's, in a sense, a book of great significance simply because so many other people read it and were so influenced by it.

It hit the shelves in 1962, as you said, and it had a huge impact and made people think a lot about how war had come in 1914, in the context of the height of the Cold War... The great story is that Kennedy was reading it at the time of the Cuban Missile Crisis, which I think is probably true.

And it does deal, in a very compelling way, with what we've just been talking about — that is, what unfolded between the 28th of June, the assassination of the Archduke, and the outbreak of war in the first days of August.

But you're quite right to describe it as you just did, as a military history, because the real weight of it is not so much its account of the outbreak of the war — although that's interesting and quite compelling in places, the way in which the war-fighting started — but what happened in that first month, which shaped the whole of the rest of the war.

WALKER: The course of the war.

WHITE: So it is really a military history, rather than what you might call a strategic history. It's a history of military operations.

But it does this in such a good way. In particular, it does such a good job of interweaving the impact of plans and technology on plans, the impact of individuals, of personalities — the great personalities of the commanders, for example, on both sides.

It's hard to look at those events without acknowledging how people like Foch and French and Ludendorff and a dozen [others]… You know, we have, as a culture, a tendency to discount the great man, great person, view of history, but the fact is, when big wars start, the capacities of individual commanders really matter.

There's a kind of drama and fatalism about the way in which the Schlieffen Plan which we touched on before — this massive movement of German forces, big right-hand sweep through Belgium down towards Paris aiming to encircle the French army — nearly worked, and it didn’t.

It didn’t work for a million different reasons, but partly just the sheer momentum. [Tuchman] is very good at describing how an army on the march, day after day, week after week — very hot weather, as it happens; it was August after all, a northern August… And at one level, the Germans just ran out of puff.

And the French and the British were withdrawing and in chaos and defeated, but the way in which they… You know, the famous words: they stand on the Marne. And push back, and therefore deny the Germans victory.

They don't, of course, destroy the German army, but leave the Germans in possession of a large swathe of France, and create the Western Front.