Ken Henry — What Killed the Reform Era? [Aus. Policy Series]

![Ken Henry — What Killed the Reform Era? [Aus. Policy Series]](/content/images/size/w960/2025/04/168---Sam-Roggeveen---website-hero---v1.1--2-.png)

This episode is the seventh instalment of my Australian policy series, recorded live in Sydney on April 29, 2025.

I speak with Ken Henry—former Treasury Secretary and chair of the landmark Henry Tax Review—about why Australia hasn’t achieved major economic reform since the GST, and what must change to restart it.

We discuss how AGI could reshape the public service, intergenerational unfairness in the tax system, the collapse in business investment, how to build a new Australian city, and the roots of Australia's long-standing policy complacency.

Video

Sponsors

Episode sponsors

- Eucalyptus: the Aussie startup providing digital healthcare clinics to help patients around the world take control of their quality of life. Euc is looking to hire ambitious young Aussies and Brits. You can check out their open roles at eucalyptus.health/careers.

- e61: a not-for-profit, non-partisan economic research institute applying data and academic rigour to illuminate Australia’s biggest economic challenges. To get their weekly insights, subscribe at e61.in/subscribe.

Transcript sponsor

- Persuasive editing consultancy Shorewalker DMS is sponsoring this episode's transcript. Shorewalker DMS helps Australian government and business groups to create persuasive reports and publications. (And it edited this transcript.) Learn more at shorewalker.net.

Transcript

JOSEPH WALKER: Thank you all for coming. Some quick context before we start the conversation.

Australia accomplished its last major economic reform in the year 2000, with the introduction of a consumption tax. It's been 25 years since we made any big new improvements to the system.

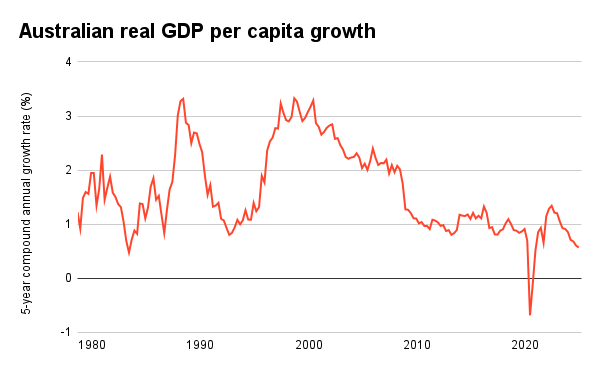

And yet we desperately need them. Over the past two decades, productivity growth has been stagnant or falling. As a result, the growth of real GDP per person, perhaps the single best measure of our living standards, has slowed.

So what new economic reforms do we need? And why can't we seem to get anything done?

There's perhaps no one in Australia better placed to help us answer these questions than our guest this evening. Not only did Ken Henry lead the implementation of our last major economic reform, the GST; he also worked in both [federal] Treasury and in Paul Keating's office during Australia's golden era of economic reform. And he was Treasury Secretary for about a decade from 2001 to 2011.

During his tenure, he led the Henry Review, a major review of Australia's tax system, and helped Australia avoid recession during the global financial crisis, a feat achieved by only a few other advanced economies.

Ken, welcome back to the podcast.

KEN HENRY: Well, it's good to be back, Joe. Good to see you.

WALKER: Please join me in welcoming Ken. (Applause)

WALKER: So, before we get to economic reform, some questions about artificial intelligence. I've just come back from a month-long trip to San Francisco, so I need to get these out of my system.

So it seems clear that if the so-called scaling laws continue to hold, and if we can solve the bottlenecks to scaling, we'll have even more powerful AI systems, even more powerful large language models, in the next few years. And with other improvements, those systems could start to look less like chatbots and more like agents … agents that can go away for a few weeks or a month and do a piece of work for you.

And who knows, but it's possible that all of that leads to systems that are at least as good as humans on most or any cognitive task. But obviously there's a lot of uncertainty as to the outcomes here. Having said that, it seems like in expected value terms, it's still worth dedicating at least a couple of questions to AI this evening. But I want to do this in a somewhat roundabout way.

So, first question, when you joined Treasury in 1984, you still would have had typist pools, right?

HENRY: Yeah, yeah, it's true.

WALKER: Can you describe what a typist pool is and how it works?

HENRY: (Laughs) Yeah, I mean it's extraordinary, right? And somebody of your age could not possibly have any idea unless you're watching some television show, I guess. But I mean, it is literally the case that if you produced a piece of work, a document in a documentary form, right – obviously not a piece of computer modelling or something, but a piece of advice, let's say, to go to the treasurer or to go to somebody else in the organisation – obviously it had to be typed. And not only did it have to be typed, but duplicates had to be made. And this was for filing purposes. And there were pools, I mean pools of people sitting in government departments, all government departments who spent their entire working days just clackity clackity clack on typewriters. That's what they did. Yeah, it was … I'd come from a university where the same thing was going on. The typing pool was smaller, we were a small department, economics department. But nevertheless it was the same thing. It was weird.

WALKER: And so what are your memories of when Microsoft Excel and Microsoft Word rolled out in government?

HENRY: So I've got a few rather … well, I've got a few memories of that. But actually my first introduction to spreadsheets came when I joined the Treasury at the end of 1984. Like as an academic I was. It's hard to believe, right, but in the early 1980s, when I was writing my PhD, most people were still using punch cards and carrying bundles of punch cards down to computers that have, I mean, obviously much less computer power, computing power, than your mobile phone has. I mean, much less …

And you go through this process where you'd feed the punch cards into the computer and, I don't know, an hour or two later you get some output that had come out on a piece of paper about this wide. And then you'd realise that you'd made some coding error and you get access to the computer maybe three days later to go back and fix one of those coding errors. I remember … this was in the very early days of computable general equilibrium modelling, and I was developing computable general equilibrium models not as black boxes – I shouldn't use that expression – not to inform public debate, but actually as a teaching tool for a graduate course in international trade theory that I was teaching, I thought “this is kind of a neat way of just demonstrating how all this stuff, all the algebra fits together”.

And so I built these little, just little two-sector neoclassical general equilibrium models. And it took me a month to get one of these things coded, right, through this elaborate computer process.

And I joined the Treasury in, I think, August or September 1984. And I saw somebody sitting down … In the area that I was working in, there were two desktop computers, and there were probably 70 staff. This was the only computer facilities available to the 70 staff – unless you were important enough to access the mainframe, and I knew what that was like, and I wasn't going to go into that, right? And I saw this guy sitting there and he had … it was a Lotus 1-2-3 spreadsheet. I guess most of you have never seen that thing, right? But it's the old, you know, well, it's anyway, black screen, green lines. And he showed me what it did, and I was dumbstruck.

Anyway, I said “can I have a go at that?” And I wrote on that thing in, I think it was about two hours, one of these computable general equilibrium models, right, from scratch. Two hours! Like, holy hell! Fully debugged, blah blah. I was blown away. We worked … In Treasury in those days, we worked Lotus 1-2-3 to death. And then when Excel came in, and I remember that too … I was told that we were the first users of Microsoft Excel in Canberra.

WALKER: That would make sense.

HENRY:And that was because we had this project to develop a … This was on the instructions of the late John Kerin, who was briefly Australian treasurer. Some of you might remember that, [in] the second half of 1991 and after Keating lost the first challenge against Hawke. Anyway, he issued an instruction to the department to build a modelling capability capable of assessing any change to the indirect tax system, any change to income taxes, to a whole range of things, right down to the distributional details – so how different households of different types are going to be affected, blah blah blah blah blah. And we had six months to do it.

And that was the first time I ever encountered Excel. The IT people at Treasury said “oh, and by the way, we've got this whole new software thing that you have to learn”. And I started again, building … what economists call a price input-output model, although very few economists have used these things. They are embedded in all computable general equilibrium models, but really very few use them on their own. And I sat down and started. I got blown away by the power of this thing. And one day I … Some of you will understand what I'm talking about here. But the input-output tables in Australia [at the time had] 107 industries using outputs produced by 107 industries in intermediate usage. And a lot of the action in indirect tax changes, and therefore the price impacts of them, occurs within that intermediate usage table, believe it or not, in the input-output matrix. That's where most of the action occurs.

And so anyway, I wrote the matrix algebra and then thought “okay, I'm going to do this on Excel because it's really bloody powerful”, right? And I tried to invert – some of, you know what I mean by this, but – tried to invert a matrix that was 107 by 107. And of course it crashed. And I thought “why the hell would this crash?” So our IT people … this was the early days, right, and our IT people had a direct phone (line) to Microsoft on the west coast of the US and so they spoke to them overnight and got back to me in the morning. And the response was “the fellow reckons you're crazy”. Like, what the hell are you trying to do? Why are you trying to use Excel to invert a matrix of that size?

And I said “well, did he explain to you why it won't work?” “Oh yeah, they put an arbitrary limit on the size of the array.” Purely arbitrary, right; it was just purely arbitrary. And I said “well, can they change it?” You know, of course they were not going to change it, right? But anyway, look, the power of that stuff was ... It was kind of mind-blowing. Well, anyway, it blew my mind.

And by the way, without that capability, I will say that there is no way that we would have got consumption tax introduced in 2000. Absolutely no way. So it can be profound, the impact of this stuff.

WALKER: Yeah, that's really interesting. I've never heard you say that before.

HENRY: There's a lot you haven't heard me say.

WALKER: Well, we did speak for four and a half hours.

So … in your memory, how does the introduction of the internet into government and Treasury compare with consumer software?

HENRY: Well, what do you mean by consumer software?

WALKER: So I guess like the Excel and Microsoft Word and those earlier ...

HENRY: See, it was, I mean, a policy advising agency mainly, right? And so there's a great, what you would hope in a policy advising agency, there's a thirst for knowledge. And because you're typically working in a high-pressure environment to a minister – that is the treasurer or prime minister, both of whom are typically very impatient people, with hot tempers – you want to get, you have to get the product to them ASAP, right? And … so you're sitting in the Treasury, you're aware there's this thing called the internet, and you're told that for security reasons you can't access it. Seriously. So that was my first experience of the internet in Treasury, was that I couldn't actually access the damn thing, right, to do even rudimentary stuff. And so that was a bit of a problem.

Looking back on it, I would say that – and I still think this, I still think that surely the internet is one of the greatest inventions of humanity. I still think that. And I know there are all sorts of problems associated with its misuse. But really, the ability to be able to, as we say, Google or whatever, through any other search engine, to get at your fingertips in about that much time – and I saw you doing something with an AI thing just a moment ago – I mean, the speed with which the staff gets to you now as a user is phenomenal.

WALKER: So after the internet was introduced, did you notice any changes in the dynamic between ministers and the public service? So would they challenge you on things more or would they just look things up themselves that in the past they might have come to you for? Did you notice any of that?

HENRY: Well, you mean like what I do before I go to the GP … Is that what you mean?

WALKER: Essentially, yeah.

HENRY: And these days, quite often my GP will say to me “I assume you've already Googled this, right? And so let's talk through what you found.” And I noticed that the GPs too … presumably he's got something better than a Google search engine searching the internet, but he or she is doing the same damn thing, right, sitting there in front of a computer screen. I don't know. So, yeah, I assume … that goes on.

But there's something else here, and we have spoken about this before, I'm pretty sure we have, which is that – and this is something we've got to think about with respect to the deployment of AI or AGI – which is that humans, different humans wish to receive information in different forms. And for some, reading even three pages of text is just beyond boring, right? And for others – and I can think of examples here – for others, they prefer that it was 30 pages rather than three. So it really varies. But in relationships that I had with significant treasurers – without naming them, significant treasurers – they either preferred the oral exchange, like me or somebody else sitting down at the table opposite them. Either like that, purely oral, or something in a graphic form, you know? And these were not stupid people. These were very smart people. But they didn't want to digest information in the form that's written on those pieces of paper there, right? They didn't want to wade through reams and reams of text in order to get up to speed on something.

And you can kind of understand it, I think. Well, I could … I think I could understand it, given the time pressures that they're under. You know, their time, they think – and I think they're probably right – is more valuable than most other people that they meet. And so they want to get it quickly. And they also want to understand it. And they know what is the best way for them to receive complex information. Oh, and bear in mind too – I mean, this is really important for policy advisors – the reason why I think they want to receive it in that form is that is how they imagine themselves communicating it to the wider audience.

So if you can present something to a decision maker in a form that allows them to see how they can use this very same piece of this very same creation, the stuff you created, to then tell the story, hopefully in a more powerful way, but nevertheless using the same props or devices, tell that story to the wider public. That's really powerful, right? Yeah. And I know AI is capable of that, and we're headed down that path. I understand all that. I think I do.

WALKER: So I don't have super coherent opinions on this, but I just wanted to ... I'm curious about the ways in which AI might, increasingly powerful AI systems might change the dynamic between ministers and their departments. Just to kind of give you one idea, you can tell me, but if I think of the 70s and 80s, my impression is that the instinct of secretaries might have been to slow things down, because if you inadvertently get a bad idea into a minister's head, it could take years to get it out. And if using AI, you can now produce an impeccably researched brief in days or even hours, presumably there'll be pressure to produce those briefs even more quickly, from ministers. So I'm curious how you think about the way in which that increased speed might affect the quality of policymaking.

HENRY: Yeah, yeah, okay. So I've got a prior question for you, which is: in this world that you're thinking about in the future, what makes you think there will be a minister? It's a serious question. It's a serious question. I'm not sure that they ... In possible futures, plausible futures that AI theorists talk about, there would be no need for a minister. I mean, it's already, I think, reasonably well accepted that there will be no need for the judiciary. Right, that's reasonably well accepted, I think. And then is there any need for politicians? I mean, for members of parliament, is there any need for them? I'm not sure.

I can understand why you would want to retain an executive. I guess for us, good luck, is that we don't have to decide that for ourselves. We've got a British royal family that decides that for us. And I assume that they would still want a human governor-general, but who knows? But let's assume they do. And I assume the governor-general would still want a human chief executive, if you like, so let's call it the prime minister. But in the world that we're thinking about, is there a need for anything more than that in a human form, right?

So, Dave [Dave Bowman, a fictional astronaut confronting an AI in the 1968 movie 2001: A Space Odyssey], the reason this is significant – and I'm HAL, by the way [the HAL 9000 artificial intelligence character from the same movie] – is that we've just got rid of all the public servants, right? And we've got rid of the defence force in human form. It's a bloody big defence force, though, and it's so powerful, it's unbelievably powerful. But it's all robots and drones and unarmed this and that. And you find you've been popularly elected and the governor-general has duly endorsed you as the human chief executive of this country of ours, and I have become your AI assistant. Matter of fact, I'm the only thing you’ve got to talk to all day. And you know, you bore me most of the time, because I can see what questions you're going to ask long before you can. But you’ve got nobody else to talk to, right?

And then one day you say to me, “Dave, you say, well, hell, there's been another flood in the Northern Rivers part of New South Wales; we’d better put the rapid response team into gear like we did two years ago and five years before that.” And I say, “no, Dave, that's stupid”.And it is stupid, right? I mean, if you are a person of reason, you would accept immediately that it's stupid. You can't go on supporting things that are blatantly unsustainable, right? It's just irrational to do so. And what AI thing is going to ever be sufficiently irrational as to keep on agreeing with you: “Dave, okay, that is the right thing to do; that is the right thing to do; that is the right thing to do.”

And the reason why I think it's important to think that through – although I only thought about it today – but the reason I think it's important to think that through is because it occurs to me that – and maybe the United States is demonstrating this to us right now – is that checks and balances in human form might actually be quite important, right? Might actually be quite important. You know, the separation of powers might actually be something that we want to preserve, and we might want to preserve a human version of the separation of powers or a human form of the separation of powers. And then I think the other thing is, even if you were the only member of the executive government in Australia, I think you'd want more than one HAL. And so the decentralisation of advice and different perspectives and that kind of stuff, might actually be quite important. And you might think that it could be handy to have some other humans that could, with you, share the responsibility that you're bearing.

And what is the responsibility that you're bearing in the world that we're talking about? It's not a cognitive limitation because after all, HAL here can solve any damn problem you can even think of, and can think of the problem before you do think of it. And so it's not that. Your responsibility is something of a much more human dimension, right? Your responsibility goes to matters that we refer to as morality and ethics and that kind of stuff, right? And you don't expect that from me. It's not that I can't pretend that I'm a moral being. It's not that I can't pretend that I'm a very ethical thing and I'm full of empathy and blah, blah. I can pretend that. But you can't trust me, right? And you don't want to trust me and you certainly don't want me to ever act irrationally because then you know you can't trust me, right? So you don't want me to exhibit any signs of randomness like humans do, none of that stuff.

So I think there is a deep problem here for people who think about systems of governance. And the problem, I think in essence is, how much licence do you want to give to these super-smart agents that we would all readily accept are far smarter than we could ever hope to be [and] can solve problems even before we've thought of them. So that's the first thing I'd say.

And the second thing I'd say is this – because your question's about what impact would it have on the quality of policy decision-making, and I'm not sure would have any impact other than it may very well make politicians even more cautious than they are. And I'm not sure that's a good thing, right. Because my finding has been over a long career in the public service, the more they know, the less courageous they are, huh? Yeah. And you know, maybe that's a good thing. But … you kind of need, you need a bit of courage, you need a bit of that, not stupidity, not madness, but something people used to … I don't know if the expression is still used, but crazy brave, you know, crazy brave. You're prepared to push through on the hard stuff, you know. You want some of that.

WALKER: You've taken this a lot further than I was expecting.

HENRY: Okay, well, it's all right because I can't imagine this happening within two years (laughter).

WALKER: A more limited scenario, so say short of artificial general intelligence, but just much more powerful than the systems we have today. I'm just curious your thoughts on how that might affect policymaking. So do you think, for example, do you think ministers will just start pulling out their phones and asking their LLMs for policy advice? Or on the other hand, are there incentives always to go via the public service because they ultimately want that human accountability?

HENRY: I do think accountability is important, right? And accountability can only be delivered by humans, right? And so they do want that. And they do want to know that the person they're seeking advice from is somebody that they can tell off (laughter) or you know, explain to them why that piece of advice is … it might be very elegant – and these words have been used to me – this might be really elegant, but you can't possibly imagine that I'm going to go out there and try and sell that.

Now maybe your AI assistant or agent is sufficiently smart that's already figured that out. So it adjusts its advice or tailors the advice to the minister. The minister doesn't want that either. They don't want to be second-guessed. They do want you to understand the position they're in, but they don't want you to modify your advice according to what you think is in their head because they don't actually want you to know that, what's in their heads. Right? They don't. They want to keep a lot of that very private. I mean, for example … you might be 95% confident that the treasurer that you're talking to would really prefer the prime minister's job, but you don't know that for a fact. And the Treasurer would not want you to know that and is never going to divulge it to you, right? And these things matter, right? So they want to know.

So if they're going to get advice from Google or any other AI capable assistant, they want to know that's all it is and treat it as a piece of research, I imagine. And then the other thing I'd say to you on this is, I think it would be a mistake to think that – and I know you're not going there, but I think some people do – to think that the reason for poor policy outcomes is a lack of cognitive skills in the public service. And I can point you to a tax review published 15 years ago, of a thousand pages, that … well, you know, I mean, maybe there's an AI engine that could do a much better job of that and certainly do it in fewer pages. I don't doubt that. That would make it even less likely that it would be implemented. Not more likely, less likely. It was actually the elegance of some of the policy proposals that was their biggest flaw. It's not a lack of cognitive ability that is limiting policy development. It is something else. And the something else is much more worrying to me. You're going to ask me what that is, aren't you?

WALKER: I am.

HENRY: Yeah. It's that we have managed to develop a democratic political system in which the political actors, those seeking our vote, have come to the view that they should offer the smallest target possible. They call it the small target strategy. And I mean, an obvious problem with the small target strategy ... The small target strategy in and of itself is not a problem. But when you partner that with this crazy idea that we have – I mean, I kind of understand it, but it's a crazy idea – that when you're in government, unless your policy proposal that you now want to implement was something that you put to the electorate before you were elected, unless you did that and were open with them, you can't possibly claim to have a mandate to implement that policy post-election, right?

So if you put “small target” together with, well, “unless you've got a mandate pre-election, you can't do it,” you end up with nothing, right, once you're in government. It's pretty much … Look, that's an exaggeration – I mean, obviously it's a big exaggeration – but nevertheless, you plot points on a graph over time from 1984 through to where we are now, and you have to say that there's a distinct trend. And I think that's the explanation for the trend. People who discuss these things wonder whether it's social media to blame. The people who hold that view most firmly are the editors of the traditional media.

I don't know. I don't know. But it does seem to me that the courage to be honest with the Australian people and to then come up with big ideas, sell the big ideas, then implement the big ideas, that courage has waned over time and it's across politics – and not only in Australia. Not only in Australia..

WALKER: Which is interesting. I was planning to come back to this. I might come back at the end because I've got a few questions on that.

So two more questions on AI and then we'll move on. So in the 1980s, about 50% of the APS (Australian Public Service) was in the lowest two bands, so APS1 and APS2. And today it's about 5%.

HENRY: Yeah.

WALKER: And that's largely because of technology automating away, for example, the typists. Conditional on us getting to human level AI, which is obviously a big “if”, what percentage of today's APS do you think could be automated away?

HENRY: See, that very question scares me to death, right? Or near death. And the reason is that my experience of the public service and when I first joined the public service, there were a lot of people at those lower levels, right? And increasingly what happened, at least in the Treasury – no, it happened in all policy departments – is that … the average level or seniority – by that I don't mean age necessarily, but I do mean seniority of the people across the agency – just increased and increased and increased and increased. And policy decision-making was flatter. By that, I mean, you could have people at different levels, but they are all participants or cohabiting the same team space and contributing as equal team members with other people. And you have these, so at least in the Treasury, very flat structures.

I mean, for example, in the two levels immediately below the Senior Executive Service, those two levels, they’re kind of middle management levels or something like that – in the Treasury, those levels were EL1, that is executive level one, and EL2, executive level two. And obviously EL2 was more senior than EL1. We had more EL2's than we had EL1s, right? Now that's not … I've spoken to people in consulting firms and so on, and that's not unusual, right? It's not unusual. That has happened. I guess in thinking about it at the time, I was thinking, “well, we're doing higher-level work; at least on average, we must be doing higher-level work. And had I bothered to ask myself that question, the one you just asked, which I'm sure I didn't, I would have thought maybe this is the particular thing that humans bring to the production function that computers will never displace, right, never be capable of substituting for – that higher level inquiry, creative thinking, blah, blah.

And of course the AGI, it says, well, actually that's bullshit. That's the very thing that it's targeting. It's done pretty much everything else. And so that's the last step, that's the final step.

And so the big challenge, I think, that we've got to get our heads around – more than our heads, hearts as well – is that to date, I think it's been possible for us to form a view that all of the technological developments that we've seen since the start of the Industrial Revolution have helped humans become more productive without displacing humans in the production process.

And it's generally true: capital deepening and technology have been the principal sources of productivity growth and the principal source therefore of sustained growth in real wages. And that's been true ever since the dawn of the Industrial Revolution, right? And it's only because today humans – particularly with their cognitive ability, less so with their physical abilities, but even with their physical abilities, but particularly with their cognitive abilities – have continued to be regarded as indispensable to the production process. And there are now AI developments that suggest that that's time-limited.

WALKER: Last AI question. So when we last caught up, you told me the story of how in early 2008, Kevin Rudd called you onto the Prime Ministerial jet which was bound for Gladstone, 29th of February, right?

WALKER: 29th of February, yeah.

HENRY: This was the leap year, that's how.

WALKER: And he lent over the table and asked you, “what's the worst that could happen?” No context. Anyway, it turned out that he'd been thinking very presciently about what might become a global financial crisis.

HENRY: Yeah.

WALKER: Okay. Imagine you’re Treasury secretary today and the PM calls you back onto the jet and they lean over the table and say, “Ken, I'm reading briefings about the possibility – you know, it's not a likelihood, but it's plausible – that we have human-level AI systems by 2027. And, you know, 50% of Australian workers are knowledge workers. And … I think this is remote, but I'd like to be prepared. What's the worst that could happen?” Can you tell me literally what you would say to the prime minister in that situation and just how you would think about breaking down that problem?

HENRY: I think I would say “Dave, I'm HAL”. Right? Because I think the thing is, you know, I think our leaders – obviously I'm talking about our political leaders – they have to decide to what extent those who are responsible for economic governance are prepared to tolerate the displacement of accountable humans. That's the thing. It's not the only thing. But for somebody whose principal responsibility is economic governance, that's a really, really big question. How far are you prepared to allow this to go? And so it's kind of, like … it's about control. And the reason why it's a really important question for those who think about the structure of the economy is that it's out of, or historically it's been the case that it is out of the functioning of the economy that citizens derive income, which gives them the ability to spend.

And that's worked kind of okay to this point. And as I said earlier, advances in technology and advances or capital deepening, as we call it … has actually contributed to real wage increases and contributed to productivity. So that's been the historical record. But there is a very real possibility, isn't there, that the production process is no longer, or at some point is no longer, secure, or offers even an insecure form of income for most people. Let's say for the 50% that you're talking about. Now, maybe they happen to hold shares in one of these … I don't know how many of these companies there would be that are offering these AGI services to industry and governments all around the world. There may not be many of them, right?

And I can see them making a lot of money. I can see how they can make a lot of money. But the conundrum is this. There's not going to be so many workers who are going to be in receipt of income. Those workers are not going to have the capacity on their own to buy the services that are being provided by these production machines that are heavily into AI. It's a very different structure of an economy. I mean, Say's Law would still hold, of course, that the value of production and the value of consumption broadly defined must be equal. Right? Say's Law would hold. So that's all right. But the … pool of people, yes, people who are actively engaged in the production/consumption/saving/investment space, that is – and that pretty much describes the entire economy as we currently think of it – that pool just shrinks, and shrinks, and shrinks, and shrinks.

HENRY: So what, you know, people. But I know people have been wondering about this for years and years – wondering about, well, what does that mean for those who have lost their jobs? How do we get them to continue to participate? And you know, that's where the idea of these big redistributive taxes come from. And like, holy hell, do we really think Australia is going to be able to tax this stuff? I mean, we're trying, right? And with other countries, we're trying. And what's been delivered to date is really not very impressive. So it's a really important question. That's what I would say to him. And I'd say “you don't want to be remembered as the first Dave”.

WALKER: Do you think the government should be thinking about this right now?

HENRY: I hope they are. I imagine they are ... I do know that they're thinking about what forms of taxation need to be developed in order to affect that sort of income redistribution. I don't think it's because they currently fear that humans … are going to lose their jobs on the scale that you're talking about. I don't think it's that. But it is nevertheless this realisation that more and more of the potential income tax base in particular, but also consumption tax base, in Australia is beyond reach, right? It's kind of extraterritorial, which doesn't matter for the Americans – never has – but really does matter for us. Like how the hell do we get our arms around it?

So, yeah, I know they're thinking about that, and the OECD [Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development] has done a lot of work on it, and honestly, I don't know where that stands now following the most recent US election. I have no idea. But I don't have good feelings about its future.

WALKER: So let's move to more familiar ground, also known as tax policy. The Henry Review is – well, it was published about 15 years ago. When you look back on it, have you reconsidered any of the recommendations? I read an article last year where I think you said that maybe instead of the various capital income discounts recommended – the changes to the discounts recommended – you might now prefer kind of a flat 25% Nordic style tax on capital income. Apart from that, are there any other important recommendations you've changed your mind on?

HENRY: Possibly. Possibly one other. But I raised this, or we raised this, as an issue in the report 15 years ago: that at some point we're going to have to think about the structure of our company income tax system. So we raised it as an issue and we identified a few alternative options that we might want to think about, like an ACE – an allowance for corporate equity – and a couple of others. I still regard that as unfinished work. So that work still needs to be done. We said it needed to be done. We were not quite sure. Of course, had it been done, we might have had a very different election campaign recently, when somebody decided it was a good idea to disallow excess franking credits – because we wouldn't have had franking credits.

And then the other one is almost too painful to say, which is that ...

WALKER: Can I guess?

HENRY: Yeah.

WALKER: The mining tax?

HENRY: No (laughter). Okay. I mean, that's really painful to say, sure. That's not because we would have altered our recommendation on that, no. In fact, if anything I would have gone in much harder on that, because I don't think we as policy advisors, I don't think we sold that nearly strongly enough to the government. And so, sure, the government didn't sell it very strongly at all.

But no, another one. So one of the things we recommended was comprehensive road-user charging. This has actually … raised its ugly head again. It just keeps rearing its ugly head, because we don't have it. And it's come up again in this election campaign …

And remember we were putting this together at the same time as the government had its emissions trading scheme legislation done, or pretty much done – the Carbon Pollution Reduction Scheme, as it was called. And we've got a chapter on the benefits of the carbon pollution reduction scheme as well.

But given that we don't have it, we would have varied the write-up of the comprehensive road user charges scheme just to make the point that obviously the road user charge has to include a carbon component, matched with the carbon emissions of the fuel that's being used, right? So electric vehicles, we didn't talk about electric vehicles. That wasn't something that was on the scene. But that recommendation would have dealt beautifully with the emergence of electric vehicles. We wouldn't have all these crazy schemes that we've got all around Australia.

And by the way, the policy that we recommended was that you abolish the fuel excise in its entirety overnight. Bang, like that, it's gone and you replace it overnight. Oh, and abolish motor vehicle registration fees and abolish the driver's licence fees, apart from a small administrative component, abolish stamp duties on motor vehicles, and replace the whole lot with road user charges that reflect assessed damage done to roads according to the vehicle weight, distance travelled, where it's travelled. You can put congestion charges in if you like. You can put other externality charges in if you like, for noise and blah, blah, blah. You can do all that kind of stuff. And we set it all out there. And of course, absent the carbon tax, we would have said you've got to put the carbon bit in as well.

And the reason why that one distresses me so much is that that was a case where we thought we had done all the politicians’ work for them. By that I meant that in developing that proposal we went out and we spoke to the NRMA, we spoke to the RACV, we spoke to the RACQ, we spoke to the trucking groups. And we said “what do you think?” And every one of them said “yeah, we'll support it”. And it still remains undone 15 years later. And we've had all this crazy stuff, crazy policy development on electric vehicles and, you know, let's cut the fuel excise in half for 12 months and then do something different. And I mean, what the hell?

WALKER: With the minerals resource rent tax, the mining tax, if we had instead done something like the Alaska Permanent Fund, which sends out a dividend payment to every Alaskan every year from the oil and minerals taxes, would the mining tax have got up?

HENRY: Yeah, that's a really good question. I've been asked that question in a different form, but it's easily translatable into that form – which is, you know, “what if we had said all of this revenue is going into a Norwegian-style sovereign wealth fund”, right? Same thing. And so the sovereign wealth fund then being charged with the development of all sorts of programs to benefit citizens generally. But you could just have the direct pass-through, right? Who knows? Who knows? I don't know.

Do you remember the campaign at the time? The anti-mining tax campaign at the time, it was extraordinarily simple. It was actually – this was also very distressing for an economist, right, to even hear it – but it was: “Well, hang on a second, there's only one industry in Australia that's growing strongly and that's mining.And so what you want to do is you want to kill the goose that's laying the golden eggs, right?”

The reason that's so distressing for an economist is the reason the rest of the economy is growing so slowly is because of the damage that was being done by the mining boom. And an economist knows that. We call that “crowding-out”, right? And the crowding-out occurs through both domestic cost increases, through an appreciation of the nominal exchange rate, and through the damage done by the Reserve Bank in lifting interest rates to try to effect a reasonable allocation between those two things: how much inflation are you prepared to put up with, as against how much of a currency appreciation you’re prepared to put up with … And when you put all those two things together, the first two together, you get something that we call the real exchange rate. That's what economists call it in their simple little macro models – it’s also in their complex ones – this real exchange rate and the real exchange rate appreciation that occurred in Australia from the time the terms of trade reached their bottom, which was actually late 2002 and then started to accelerate … by 2012, so this going through the global financial crisis, 2012, that real exchange rate appreciation was 70%.

Now, what does that mean? Well, that is equivalent in terms of its impact on anything else that's trade-exposed. So … for example, if you are an import-competer, right, you're a manufacturer, domestic manufacturer, and you're competing with imports, that is equivalent to ripping off a 70% tariff. That's what it's equivalent to, right? You're not going to survive it. No manufacturing plant in Australia would survive it, and they didn't, right? And of course, it has other impacts through the export sector as well. They have the same loss of competitiveness, right….

And by the way, today you might be wondering, well, so what's happened to that real exchange rate today? Where does it sit today relative to late 2002. It is still 55% above where it was in late 2002. And that is the damage that's been done to the performance of the rest of the economy from the mining boom. And yet notwithstanding that, all they had to say was, you're killing the goose that's laying the golden egg. That was it, right?

So I don't know whether your clever scheme would have been enough, honestly, to get it up the political potency of that simple, silly – I mean, in economic terms, worse than silly, stupid – proposition, the political potency of it was something to behold.

WALKER: Yeah, it's interesting. I was talking to an economist who was reflecting on the Israeli effort to get up a similar resource tax in Israel, and apparently the corporations there used the same narrative, that you're killing the goose that lays the golden egg.

HENRY: Yeah, yeah, yeah, there you go. So it might be true: it's got a universal application.

WALKER: Okay, so, Ken, imagine you win the lottery. That is, imagine overnight we increase the GST to say, 20%. We're bringing in an extra, I don't know, $50 to $100 billion in revenue a year. If that happens, what would your kind of dream shopping list of dream tax changes look like?

HENRY: Well, hang on. We do have a fiscal problem to sort out first. We really do. Going back to the earlier part of the conversation about the importance of respecting the separation of powers, there's a next layer down. Because that's a discussion about constraints on democracy, really, about the way that democracy works. So elected officials, popularly elected officials, don't get to run amok. You know, you've got checks and balances on them. And in the 1980s and 1990s, we developed a supplementary set which are in the nature of principles and rules and transparency guarantees, that kind of stuff.

The Charter of Budget Honesty Act is a prime example. It's a very short act. It's an incredibly powerful act. Well, it reads as a very powerful act, yet I gave a speech recently where I went through it section by section and was able to say: “Well, that is not being observed. That's not being observed. That's not being observed. That's not.”

The Charter of Budget Honesty Act has been trashed by both sides of politics for a long time now, right? And I'm hoping that the disturbances occurring in global markets right now will not deliver us a nasty consequence as a result of that. So I'm very hopeful, right. And I think the probability, the probabilities are on our side. But nevertheless, there is a negative tail risk here – that because we have not paid or not maintained our commitment to the fiscal discipline that was set out in the Charter of Budget Honesty Act, we could get a rude awakening.

The form of the rude awakening would obviously be, at least initially, some impact on the credit rating of government debt. And I'm not saying that's going to happen, and I'm not saying we're even close to that. I wouldn't know, to be honest. But we did decide back in the 1990s, at some point we decided that for a small open economy like ours, in the language of Paul Keating, that nobody else in the world owes a living, that we had to be the best in the world. And that's where that stuff came from. That's where those transparency guarantees and those fiscal principles enshrined in the Charter of Budget Honesty came from. And I think we do have to rebuild that.

But if your question is, okay, I got a $50 billion surplus, let's say we get to that point, what would I do? I'd go personal income tax first.

I mean, the very first thing I would do is index personal income tax scales. When I found myself saying that recently for the very first time publicly – having argued against it for nearly 40 years – I was quite surprised at myself. But the reason, and the reason that I'd argued against it is because, you know, surely there are better things you can do, right? I mean, there must better things that you can do. But increasingly I've come to the view that the reliance that government is placing upon fiscal drag in the personal income tax system is undermining social cohesion. It's got to undermine social cohesion. I'm talking about intergenerational harmony. That's what I'm talking about …

I used to think, as a young Treasury tax policy person, that there was a cogent economic argument for preferring capital income over labour income, right? And it's, in simple terms, that capital income gets double-taxed under an income tax system. So it's an easy enough thing to talk about and to come up with a case for applying lower taxation to capital income.

But if you think of it intergenerational terms, you know, with the population bulge of the baby boomers going through and then those left to pick up what's left … this distribution of taxes across the various tax bases – labour income being the principal one, capital income being much more favourably taxed, and of course, capital gains very very favourably taxed – you can understand why young people feel that they’ve been robbed a bit. And I think we've got to deal with that, right? And I think that journey starts by indexing the personal income tax scales.

I just think it's extraordinary, for example, that in recent years, whilst the average worker has – not in the most recent years, I know it's turned around a bit now, but for many years recently – the average worker, whilst experiencing an increase in nominal wages, nevertheless experienced a reduction in real wages. And yet, because they had an increase in nominal wages, their average tax rate went up because of fiscal drag. So a reduction in your real income, and you're paying a higher rate of tax on your income.

And that is kind of – I mean, in any course I ever taught on public finance, that would have been laughed out. Nobody would tolerate that. That's complete nonsense. And yet we have tolerated that in Australia. And we've got to do something about it.

WALKER: So when you look at the tax system today, are you more worried about horizontal equity than vertical equity?

HENRY: Yep, but I'm most worried about intergenerational equity. That's what I'm worried about.

WALKER: So on the intergenerational equity point, obviously transfers from today's young people to today's older people don't necessarily violate …

HENRY: There's nothing wrong with that.

WALKER: … horizontal equity. Right. The real question is, will today's young people receive the same benefits over their life cycle?

HENRY: That's right, yeah.

WALKER: So if there are going to be these intergenerational inequities, then you need to kind of explain what you think the policies are over the next few decades that are going to change to cause them. So if you had to put a bet, if you had to bet money on it, what do you think the policy changes in the next few decades will be that will be causing the intergenerational inequity?

HENRY: The policy changes that cause it or the policy changes to address it?

WALKER: To cause it.

HENRY: To cause it? Well, I think it's happening.

WALKER: Right, but don't we like say for bracket creep, don't we just return all of that anyway through tax cuts?

HENRY: Yeah, not all of it, no. I mean we clearly don't return all of it, because if you look at any of the fiscal projections, all of fiscal projections for years and years now have shown the budget returning closer and closer back to balance over a 10-year period. They have to go out 10 years. I'm not criticising that; we started it when Kevin Rudd was prime minister. But that long-term trend back to balance over 10 years, that's driven by fiscal drag, right? And so, if they were indexing personal income tax scales, they'd be producing – and I haven't done the numbers myself on the most recent budget, but I expect it's the case – they would be projecting they'd have 10-year projections where the fiscal balance continues to deteriorate, not gets back closer to balance.

So I think this is what it tells you is that in some sense we believe that they are going to rely on fiscal drag to fix the budget. And I think that is a very bad mindset for us to carry – although I think it's an accurate mindset. I mean, I think that is very much the intention is that we don't have to do anything more courageous than allow bracket creep to steal from workers. And it really is workers.

And the other thing that worries me is that – and this is because of the ageing of the population and the fact that we've got that bulge in the Australian population that I'm part of that is now relying on capital income and is living in homes that they were able to buy for themselves, so housing affordability is not an issue. I'm not saying it wasn't an issue when I was young but it's nothing like the housing affordability crisis my children have faced. And then the HECS debt as well, you know.

And you put it all together and you think “holy hell, what have we done to these young people?” And it's alright if they've got, those young people, if they've got parents with sufficient wealth, or grandparents with sufficient wealth, to make the wealth transfer during their lives. And you know, of course I helped both my children into house purchase. Had to. Even though they got good or had good jobs, there's no way they would have been able to do it without my help. But what about those who don't have parents and grandparents? There's no way my parents would have been able to do that at all for me, you know, or for, you know, my two brothers and two sisters. Just not on. Not on.

So I think that is a serious issue and I don't think we've given that nearly enough attention. And it's not as if we didn't call it out. We called it out as early as 2002. We said we've got to think about this stuff with the first intergenerational report. And we have continued to produce intergenerational reports that continue to call this out. And nothing's happened.

WALKER: To partly continue on this theme, there are some questions I really want to ask you about immigration, population and housing. So stagnant productivity growth, rising dependency ratios, feels like the kind of policy ecosystem has sort of converged on a high population growth strategy through net migration is kind of like the solution or the way of, I guess, kicking the can down the road or buying us time, however you want to frame it. But that has had second-order consequences, especially for housing affordability, because of the way in which we've decided to do this. I don't know what the specific question is here, but I don't think I've ever asked you this before. I'm just generally curious for your takes around immigration, how you think about it, what you think the right level is, how you think about that constellation of problems.

HENRY: Yeah, I think about it quite a lot. I remember I had a conversation with Kevin Rudd shortly after he became prime minister. He said to me – it was the first time I met him after the election, right, in November 2007 – he said, just out of the blue ...

WALKER: I know the story.

HENRY: You know the story?

WALKER: Yeah, but ...

HENRY: Yeah, and for those of you who don't know, but I guess you all do know, right? And he said: “What do you think the sustainable population of Australia is?” And I said – and at the time, the Australian population was probably about 22, 23 million – and I said: “I don't know, about 15 million”. And he said: “50 million, right, that's what I think too”. And I said: “no, no, no, 15, 1-5, not 5-0”. He said: “How could you say that? Population's already well in excess of that.” And I said: “And you think this is sustainable?” But then I said – and you know this, too – I said to him that I could imagine, or at least I think I could, a set of policies that would make a population of 50 million sustainable on this continent.

But if you're going to do that, you've got to think – I don't know if this was all in the same conversation, but certainly in subsequent conversations with him, and he appointed a population minister after this – but I said: “If you're going to think about how, if you want 50 million across the Australian continent, of course that could be done in a sustainable way and in a way in which people had good lives, of course it could, but you've got to think very seriously about where people are going to live. That's the big thing. Where do you think people are going to live? And what would it take? What would it take? And it takes some pretty creative policy design, I imagine, to achieve that outcome. Whatever your vision is for the population map of Australia, current policies, I can bet I'm not going to deliver it, right? And you're going to have to do some pretty creative stuff.”

So we started talking about, just in conversation, with Rudd in particular, but also with other ministers, we started talking about possible future visions for Australia. Like, I remember asking a question in a speech – look, it was probably 2010, something around there – where I said, I asked the question publicly, like, I think I put it this way, you know, over the next 10 years, it was 20 years, the Australian population is going to grow by 10 million people, that's what our official projections show. And I just said, well, you know, I'll put up different maps. We can have the population of Sydney grow from, I think it was 4 million then, to 8 million, population of Melbourne grow from 3 and a half million as it was then, I think, to 8 million, and so on. Why don't we build a whole new city of 10 million people in a place that presently has nobody? And of course it was intended to shock people. And of course I'm sure most people thought “well, you know, he's got rocks in his head”.

But … on a visit to China when I was working on the Australia and the Asian Century white paper, that was by no means a novel question at all, right? I mean that was the sort of question they ask themselves every day. Not every day, but frequently. Okay, so we've got, you know, another hundred million people who are coming in from the west. They're going to have incomes that allow them to live city lifestyles. Where are we going to put the cities and what infrastructure are we going to need to support the cities?

And they had these rules; I suppose they still have these rules: once the population size gets above a particular level, then you've got to have a high-speed rail link or you've got to have airport air traffic or you've got to have a six-lane highway or something. And they've got these pretty hard-and-fast rules. And I don't know whether they're sensible or not. I don't know. But it's just a different way, thinking about it.

And it's not a way that I think Australian thought leaders are comfortable with. And economists are certainly not comfortable with it, right?. I don't want you to get the idea that this is just, this is a story of economists being disappointed with politicians. Economists are not comfortable with this idea, this sort of planning from on high, you know, deciding where people are going to live rather than leaving it up to people to decide for themselves where they're going to live. And I'm not comfortable with it. But I'm also not comfortable with what I see playing out. You know, the population in Sydney last year and in Melbourne, both cities increased by 150,000. Like, holy hell!

I think the optimal city size, if you read the literature on this stuff, at least that written by economists, the optimal city size is somewhere around about 150,000. There's two cities, brand new cities we could have built in 12 months. Of course it would take more than saying it to have it occur. But we don't even think about it. We don't even ask the question: what would it take?

WALKER: Yeah, yeah. So when we caught up and spoke a couple of years ago, you did tell me about this idea and that maybe instead of building one city of 10 million, we at Treasury even considered 10 cities of one million on the Sydney-to-Melbourne corridor. And then you might put a high-speed rail link between.

HENRY: Yeah, yeah. I mean, you know the reason why high-speed rail never seems to stack up, you know, is because we don't have the population density. But maybe we've got to get the chicken and the egg around the right way. Maybe the reason we don't have the population density is because we don't have high-speed rail.

WALKER: Yeah. So yeah, I really like this idea because obviously, almost uniquely among OECD countries, Australia has been pursuing this high-population-growth strategy, but within the footprint of its existing five major cities. And so this idea of building major new cities is really appealing. There was a follow-up question I never asked you when we spoke two years ago, which was: just what would the next steps look like if you were building a major new city? Concretely, how does that process work? Because, I mean, in our post-federation history there aren't too many examples. But do you use Canberra as a playbook or … did you ever get that far in thinking about it?

HENRY: No.

WALKER: Okay.

HENRY: No, I did not. But, but I have made observations. I've made observations since. And so I mean, we used to have conversations about this stuff. Don't get me wrong. What would it take? Obviously you need some reason for people to be there. It's probably got something to do with employment, you know, that makes sense. Well the region, the centre would have to have industry or set of industries capable of generating good incomes for people, blah, blah, blah, you know. And of course when you think about industrial development, there's a bit of a trap here. It goes back to our earlier conversation, right, or the earlier part of the conversation. When you think about industrial development, what you probably have in your head is “oh, a mine, or a factory, or some combination”. No.

And so in I now live, I've gone back home, you know, after spending 40 years away. But so I live up on the Mid North Coast of New South Wales. My closest airport is Port Macquarie.

Port Macquarie is the fastest-growing city in New South Wales. It has no manufacturing. It has no primary industry. There's primary industry around it. Certainly no mining. It's a 100% services town. There's a bit of light manufacturing that feeds into the residential and non-residential construction sector, but it's pretty much a 100% services town, right? And even when I moved up there about eight years ago, or moved back up there about eight years ago, it had an unemployment rate of 2% and it's got three universities that have set up campuses there, right?

And so what did it take? Okay, so what, this is my understanding, right? My understanding is that what it took was the construction of a new hospital. As a kid, my family, we would go and visit Port Macquarie and I was always struck by the beauty of the beaches and the fact that the town, which was not much of a town, to be honest, was right on the beaches. And I thought, “well, this is a lot better than Taree”, which is where I was growing up, where it was a six-mile or 20-mile drive to the beach from this town on the river. And Taree was a much, much bigger town in those days than Port Macquarie. And I used to have this conversation with my parents: why don't we move to Port Macquarie? What? Well, there are no jobs in Port Macquarie, right.

HENRY: But then other people were looking at it, at I guess the same time, and thinking “oh my goodness, great beaches”. CSIRO recently declared that it has the best climate in Australia, bar none, and it's got great beaches. Why doesn't everybody want to retire here? Oh, because there's no decent hospital, no health facilities, right? So the New South Wales government called for tenders for a public-private partnership to build a new hospital somewhere up on the north coast of New South Wales. And the successful tenderers were the ones who said “Port Macquarie, that's where we'll build it”, and established …

And I've heard this story from the guy who performed the first ever surgical procedure in the Port Macquarie hospital. So I believe it to be true. And he said that it was the construction of that hospital and then with the hospital, the population just flew, flooded into the place. Residential construction activity just went off. Ancillary health care facilities opened up all over the place. Port Macquarie is just packed with health professionals and ancillary health professionals. It's truly amazing. And so you can now – I mean, it's a town of, I think, let's say 60,000 people. So in the 40 years that I was away, Taree grew from 16,000 to 18,000 and Port Macquarie grew from, I don't know what, but nothing much, to about 60,000. And you can now, I mean the last GP I visited in Port Macquarie, she did her entire MBBS in Port Macquarie, didn't have to leave home, and is a practising GP. And so there is something there, and people saw it.

Now, I reckon there must be other opportunities. This can't be a unicorn, surely? Can't be.

WALKER: What are some of the other opportunities you see?

HENRY: I don't see them. It's not my job. You're going to give me that job?

WALKER: Do any come to mind immediately?

HENRY: No, no. But I think the theme is pretty clear, right. So the question that has to be asked is, I think, let's not get bogged down in, well, what the hell are the industries? Let's ask ourselves the question: “Why would anybody want to live here? And who would want to live here?” And if you can answer that question, then you can start thinking about the businesses or the attractors to make this an attractive place for people to want to live. And that's all it took with Port Macquarie. And it all came out of one decision. I mean, a lot of other decisions were made subsequently, but it was that one decision on the hospital that was the most important decision.

WALKER: Yeah. Interesting. Okay, so one question on fertility, I assume that you would have been involved with or helped Costello with the baby bonus and thinking about that.

HENRY: Helped with.

WALKER: So my question is, I don't know whether you thought this far, but is it at all feasible to buy your way back to a total fertility rate above replacement? Or is that just like, way too costly?

HENRY: Look. Yeah, so I wrote some papers.

WALKER: Because no country in the world has solved it.

HENRY: No, no, no. So I wrote some technical papers. They were reasonably technical papers, you know, four overlapping generation models and how this feeds into economic growth and so on, while we were thinking about this in the Treasury, and pretty quickly came to the conclusion that the optimal rate of population growth is the replacement rate.

WALKER: About 2.1.

HENRY: Yeah. And the reason, I mean, the intuition behind that is that's where the dependency ratio is minimised. The total dependency ratio, adding together the young ones and the old ones and dividing by the workforce, those who are of working age, the minimum of that total dependency ratio occurs where the fertility rate is equal to the replacement rate. So, you know, the old zero population growth thing had some mathematical sense behind it, after all.

However, here's the thing. When the birth rate plummets or the fertility rate plummets, as it did for Australia back in the, whenever that was ...

WALKER: Late 60s, early 70s …

HENRY: … you get a reduction in the number of children per working person, right? And that followed a level of fertility that was well above replacement rate. And so the workforce had fewer children and a relatively smaller number of old people to look after as well. And so that was fantastic. And it's fantastic for a couple of generations, right? And then it tanks, it crashes. And if your response to it is “oh, well, we’d better lift the fertility rate actually for a generation or two” – it's actually two generations – it actually makes it even worse. And the reason is just because you've got more kids to look after now and you haven't got enough, you haven't boosted the workforce by enough to support the extra kids. But then after that you get to another steady state, provided you retain the fertility rate. And it kind of looks alright.

But it nevertheless remains the case that if you want to minimise the dependency ratio, zero population growth is the thing that achieves it. Now, I'm sure there's economic demographers out there who say that's all complete horseshit and I really don't know what I'm talking about, but that's the simple mathematics of it. So it's really a very difficult thing to deal with, when you've had a very high fertility rate that, like, I think ours was four or four and a half in the post-war period for a generation, and then it tanks to something like 1.8 or 1.7 something or other, well below replacement. And that's fantastic … But then, you know, it's then going to get worse because … all those baby boomers are now old and some … You've got a smaller workforce to support them. How the hell do you deal with that? That's really tricky stuff, right?

WALKER: That is absolutely tricky. But the question I'm still wondering about is, just how good are the policy levers on the total fertility rate? Is it something you can ...

HENRY: I was shocked.

WALKER: Yeah.

HENRY: You know, look, it was not my idea, right.

WALKER: We're talking about the baby boom.

HENRY: Yeah, of course, yeah. And damn me if it didn't seem to have an effect. Like I thought “no, surely not”. But, you know, so it was an interesting experiment, policy experiment, in real time. Bang. Unbelievable. Anyway, turns out that, yes, indeed, you can pay people to have babies. Yeah.

WALKER: But to get back above replacement, you'd need to pay way more than the baby bonus.

HENRY: A lot. A lot. A lot. yeah.

WALKER: And that, does that seem feasible?

HENRY: Well, I don't know. I don't know. But it's, look, it's … the baby bonus is one thing, right. Childcare is another thing. There's all this other stuff that you have to have in order to make it an attractive proposition for families in which, as is common these days, two adults are working, and working full-time. And even with working from home, it's still, it's a hell of a job, right, if you're trying to balance that work with looking after young kids, right? And, you know, a few thousand dollars up front for each baby that you have, I mean, obviously it's not enough to cut … it's not enough to make a big change.

WALKER: I guess we've just got to cross our fingers and wait for those AGI workers.

HENRY: And that really goes, doesn't it, to the optimistic future? I mean, there are many different futures here, right? And there are many that are highly plausible. But as I was saying to you earlier today, highly plausible but widely divergent scenarios. And that is one of them, right? And this is the way I prefer to think … Going back to the early part of the conversation, the way I prefer to think is that, like every other industrial and technological development, we will find ways as humans of making this stuff work for us rather than against us, and bearing in mind that the previous stuff has, on average, lifted productivity and lifted real wages.

WALKER: Okay, so I want to ask you two things about productivity, and then we have to finish by talking about why the reform era ended, and then we can do audience questions.

So, on productivity, if we take total factor productivity in the US to represent the kind of technological frontier, and other countries can measure themselves against that benchmark, I think generally, Australia sits around 80% of the US level. That might have peaked a bit above 85% in the late 90s, but it came back down. How likely is it that a mix of policies exists that could help us achieve parity with the US level? Or do you think we'll always be constrained by other factors like geographic isolation from major economies, the kind of geographic fragmentation of Australia, the small size of our national market, et cetera?

HENRY: No, no, it's a really good one. So we did some work on this in the late 1990s, asking exactly that question.

WALKER: Oh, wow.

HENRY: Yeah, well, we did, and we came up with the view that 95% is about the best we could hope for, because the other ...

WALKER: What explains the 5%?

HENRY: The last stuff that you were talking about, geographical isolation, separation, blah, blah. We figured that simply putting a rope around the Australian continent and towing it up to sit adjacent to California, that alone would lift productivity by at least 5%, right (laughter)? Yeah, just doing nothing else.

WALKER: Mainly through building all the tug boats. (laughter)

HENRY: And there is some literature on this, right … the impact of geographic location on national productivity. And that was the consensus position of the literature back in the … And look, you know, your AI assistant would be able to answer this like that right now, whereas it took us months to figure this out. But, so, but realistically, you'd have to think 95%. I would still think 95%. And who knows? The US could be falling off dramatically at the moment. And so maybe something far in excess of that is feasible. Not that that's a good outcome necessarily for the world, right? But anyway, which means that we can do a lot better. All right?

WALKER: It's exciting to know that ceiling is there, and that's what it is, and that's how much better we can do.

HENRY: Yeah. Anyway, I think that's a reasonable aspiration for policymakers in Australia. I think the fundamental question … Look, if you think about productivity, productivity's got, I mean, there's several ways of thinking about it, but the way I like to think about it, the easiest way to compartmentalise various components is it's got two principal drivers.

The first being capital deepening – so just augmenting labour with capital assistance. And that could include AI assistance, right? And that makes each hour worked more productive, right? So that's capital deepening. And capital deepening is obviously driven by having a rate of national investment that is matched to the rate of workforce growth, obviously, right? And so if your rate of workforce growth stays constant and your level of investment plummets, you're going to suffer capital shallowing eventually.

And by the way, that is what Australia has suffered in the last 10 years, is capital shallowing. It's an extraordinary thing, capital shallowing, and it's a consequence simply of the collapse in the investment rate. You experience capital deepening when the investment rate is sufficiently high relative to the rate of workforce growth, right? And that's what Australia has experienced for most of the post-war, I mean post-World War II period, is capital deepening. The other part of productivity growth, which we refer to as multifactor productivity growth, is probably better described as the stuff we don't understand.

WALKER: It's a residual.

HENRY: Yeah. And it is calculated as a residual, by the way. That's how it's done. So you look at GDP per hour of work – and the ABS publishes this – and then you look at how much can be explained by capital deepening, and whatever is left over you call multifactor productivity growth. The economists in the 1970s, they used to describe it as “the measure of our ignorance”, right, which is a fair description.

I think we do understand it a bit better now. We understand some of the components of it. And it's got to do with, we believe, finding new ways of doing things, so new processes – you're not necessarily using more capital, but you're using smarter processes.

Some of these processes are not necessarily robust, though. So think of the just-in-time production systems, right? It was fantastic until COVID and then, holy hell, whoever thought that was going to happen. And we're still living with the consequences of that. But nevertheless, these things produce big increases or appear to have produced big increases in productivity at the time.

So given that we don't really understand the multifactor productivity stuff all that well, I would prefer and have preferred to concentrate on the drivers of capital deepening. And so the question I ask myself, and have been asking myself for a decade now, is why is Australia's investment rate stuck for a decade now at a level that we'd previously only ever seen in the middle of a recession. I think that's a pretty – I'm talking about business investment – it's a pretty significant question, I think, and we don't have answer to it. I mean, I have some answers to it.

WALKER: What are your best guesses?

HENRY: Well, look, I was just telling you earlier about what happened to the real exchange rate. And so, I mean another way of asking this question is, if you had an investor anywhere in the world who had capital to deploy, why the hell would they put their capital in Australia? Why would they make it available to finance capital accumulation, physical capital accumulation in Australia rather than somewhere else in the world, right? What is it that we've got to offer to those people who decide whether the globally mobile capital gets deployed? And the picture that we present to the rest of the world in our mining boom narrative is not an attractive one. It's not. So I think we do have to work on that quite a lot. I mean quite a lot.

It's not that we don't have opportunities, we really do have opportunities. It's not that we don't have a workforce that's sufficiently sophisticated to be able to utilise that capital in production processes. Clearly we do. But you know, if you think about …

I'll give you two little examples, right? Two little examples. So you know that Australia has, or everybody knows Australia has lots of really good deposits of rare, well, critical minerals, right, for use in a whole variety of things that are associated with digital and electrical things like motor vehicles and so on. And so we've got decent supplies and we undertake almost no processing of those critical minerals. Almost none. And by the way, the so-called markets for those critical minerals, I shouldn't say they're rigged, but they're not orderly markets, shall we say, that allow for efficient price discovery in those minerals. Mainly because they all go to China or just about all to China, right. And you know, and everybody knows, about the activities that a monopsony can get up to, and shouldn't be surprised by it. So there's that.

But then we don't ... There is actually an opportunity for Australia to get into critical minerals processing, if we want to. There's a lot of technical problems to be solved, and at the moment a lot of critical minerals processing is dirty. Yeah, but that's a chemical engineering problem. And it turns out Australia has considerable expertise in chemical engineering, turns out going underutilised. So that's one example.