Australia’s ‘Great Stagnation’: Everything You Need to Know About The Productivity Crisis — Greg Kaplan & Michael Brennan

The 2010s witnessed Australia’s weakest productivity growth in six decades.

How much of the slowdown is homegrown? How much reflects the broader “great stagnation” plaguing the West?

How much is simply an artefact of the way “productivity” is measured?

And what would a credible new growth model for Australia—with its distinctive reliance on mining over manufacturing—actually look like?

To answer these questions and more, I’m joined by two of Australia’s smartest economists.

Greg Kaplan is the Alvin H. Baum Professor of Economics at the University of Chicago. He is also the cofounder and chairman of e61, a non-partisan economic economic research institute in Australia.

Michael Brennan is the CEO of e61. He was previously chair of Australia's Productivity Commission and a Deputy Secretary of the Australian Treasury.

We discuss:

- the forces behind falling construction productivity;

- how to think about “Australia’s most productive company”;

- where to find quality gains in the services sector;

- what we can learn from the stunning innovativeness of Australia’s agricultural industry;

- why we need new economic engines beyond the Sydney–Melbourne duopoly;

- and much, much more.

Video

Sponsors

- Eucalyptus: the Aussie startup providing digital healthcare clinics to help patients around the world take control of their quality of life. Euc is looking to hire ambitious young Aussies and Brits. You can check out their open roles at eucalyptus.health/careers.

- Vanta: helps businesses automate security and compliance needs. For a limited time, get one thousand dollars off Vanta at vanta.com/joe. Use the discount code "JOE".

Transcript

JOSEPH WALKER: Today it is my great pleasure to be speaking with Greg Kaplan and Michael Brennan here at e61’s Sydney office.

Greg is one of the smartest macroeconomists in the world. He’s the co-author of one of my favourite papers on the US housing bubble. He’s a professor at Chicago, but he spends part of his time back in Sydney where he’s a co-founder at e61. e61 is a non-partisan, independent economic research institute.

I’m also joined by Michael Brennan. Michael is one of the most knowledgeable economists I’ve met. He’s the CEO at e61, and he has deep public policy experience. Prior to his role at e61, he was chair of Australia’s Productivity Commission, which is a very cool institution, essentially a think-tank for the Australian government that does deep economic research. Before that, Michael was a deputy secretary in the Federal Treasury. He’s also worked in the Victorian State Treasury and been a senior adviser to treasurers and finance ministers at both the state and federal levels.

So, guys, welcome to the podcast.

GREG KAPLAN: Thanks for having us.

MICHAEL BRENNAN: Great to be here. Thanks, Joe.

WALKER: Basically, what’s going to happen is for the next couple of hours I’m going to pepper Greg and Michael with all of my untutored questions, and they’re going to teach me a few things about economic and productivity growth, and how to get more of them in Australia.

Obviously, we are three patriotic Australians, but this conversation I think will still have interest for an international audience, in two ways. Firstly, we’ll be talking about productivity more broadly as an economic object. Secondly, people might be interested to hear how a smaller country of about 27 million people, like Australia, thinks about how to get more productivity growth, because obviously this is a problem across the West.

I actually want to pick up where we left off a couple of weeks ago. The three of us were chatting and you two were riffing on construction productivity and why it has stagnated. It’s interesting that it’s stagnated not just in Australia but across the West.

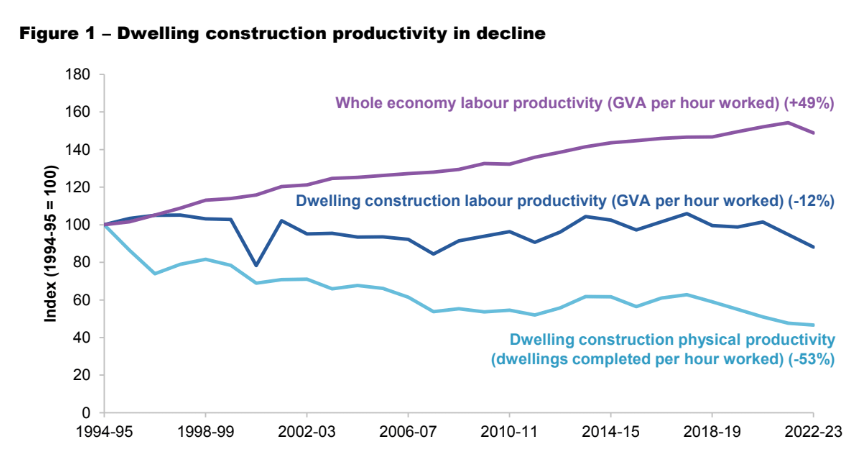

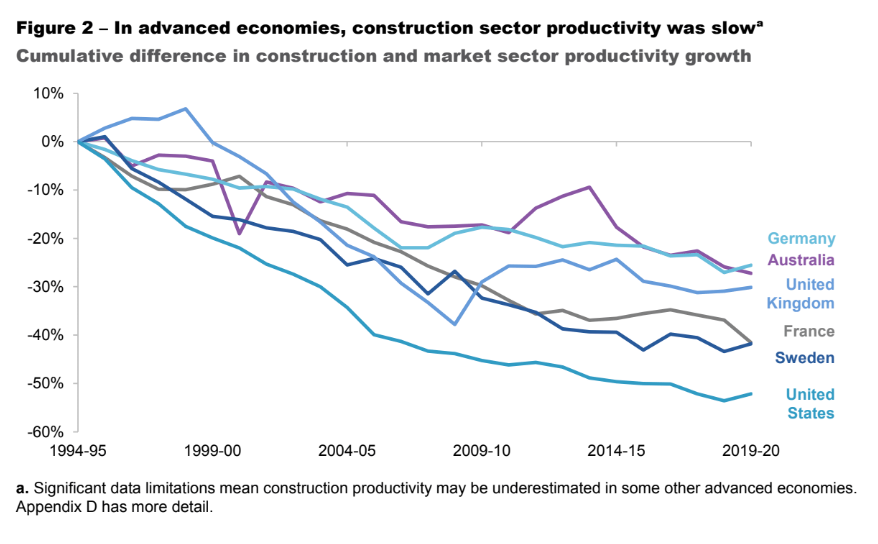

I’ll put these charts up on the video version of this episode for people watching on YouTube, Twitter and Substack: here we’ve got Australia’s housing construction productivity decline—this is labour productivity—from a report the Productivity Commission published several months ago.

And we also have a chart for advanced economies, so we can see clearly this is a problem around the [West].

When we were catching up, you sketched a theoretical argument tied to fixed inputs and the durable nature of housing. I don’t think I’d heard that argument before. Could you just recap that idea? And have you taken it any further since we last caught up?

BRENNAN: I’ll have a first shot. Thanks, Joe. This theory, maybe wild conjecture—listeners can be the judge. But the starting point was thinking about this paradox. Why are we so much better, and getting better over time, at building things in factories, but no better at building things out in a paddock or in a dense urban environment?

There may be a whole range of reasons for that. Obviously there’s been a lot of speculation about the ways we could make construction more like manufacturing—bringing elements of the process into the factory through modular housing, etc.

But one of the things we were thinking about was: is construction fundamentally different in that, in every other industry, say manufacturing, the annual production each year gets repeated? The most efficient producers of any given good are producing again next year and the following year.

To the extent the product is growing, there’s an incremental bit that maybe is built by a factory that’s less conducive to high productivity, but those (what we economists describe as) infra-marginal units are getting repeated every year.

Construction is fundamentally different: because in construction you’re not repeating those infra-marginal units. If you’ve already built housing in the most propitious, easy-to-build areas—those most conducive to a high-productivity build—you can’t reproduce that next year. That’s not going to be factored into the production statistics. You’re building, one would expect, in successively harder and harder places.

Now, that’s an empirical claim. It may or may not be true. It might be that, particularly with greenfields housing, it really doesn’t matter; you can just move further out in concentric circles from the city and it’s just as easy. Maybe that’s true.

But it just struck us as something that might be a little bit distinct about construction: that sense that you don’t get to repeat the easy units each year, and therefore it could be just a little bit harder for measured productivity in the construction sector to continue to rise year on year the way we expect it might in other sectors.

WALKER: To make sure I understand: there’s this observation that you don’t have economies of scale in construction like in, say, car manufacturing where every model’s the same. In construction, most houses or units are bespoke in some sense.

But you’re taking this further: the units quickly become different or more bespoke, which bakes in the productivity slowdown. Is that the idea?

BRENNAN: Yeah. Also, in cars, if the most efficient factory is in Detroit—or wherever—it’s producing those high-productivity amounts of output year after year.

In construction, you might have used up the highest-productivity sites, if you think that sites might be conducive to a more efficient build. You’ve exhausted them.

The distinction with construction is that it’s an increment to the stock. That’s what you’re doing each year. You don’t get to revisit the stock and reproduce that each year, so the infra-marginal units don’t get repeated in the same way.

WALKER: Okay, I get it now.

KAPLAN: There are two features of housing construction which are a bit different from cars. One is the durability of the good: a building is extremely durable relative to a car. The other is the reproducibility of the key factor, which is land; which is extremely irreproducible.

But even with improved land, you have to think about critical infrastructure. It’s a continuum, and there is a role for government because part of what makes land “reproducible” is whether you invest in the infrastructure to make a new set of greenfield sites usable. But that difference means you don’t get to reproduce those infra-marginal builds as often, and when you do, you’re moving up a marginal cost curve—down a supply curve—as you do it.

WALKER: Do you have a hunch for how important this might be empirically?

BRENNAN: It’s hard to know. One of our researchers at e61, Matthew Maltman, has been working on a paper in relation to productivity growth in the construction sector in New Zealand, exploiting the natural experiment of when planning laws were substantially liberalised.

The result appears to be an uptick in measured construction productivity post a liberalisation like that, but it does fade again over time.

This is not a robust empirical test, but that set of facts would be consistent with this theory: there’s an initial almost gold rush—“here’s a new opportunity”—the best, easiest and most economically viable builds will be done first, thereby you see a bit of a rise in construction productivity. But it will probably abate over tim as the best sites are done and you move on to the next lot. I’d have to check the percentage improvement in that instance, but it was a noticeable uptick.

WALKER: Here’s a thought experiment. Think of all the levers we have to get construction productivity growing again.

There are the classic planning regulations—the kind of things YIMBYs are concerned with, like what Matt was looking at. There are also regulations that apply to the labour side of the construction industry: union rules, enterprise bargaining agreements. [There are] building codes—all of those types of regulations. There are things like worker quality; the structure and fragmentation of the industry; how well it innovates; maybe tax incentives that cause it to be so fragmented, because it is a super-fragmented industry.

(I’m trying to remember the CEDA report that came out recently, but I think it said 98.5 per cent of Australian construction firms have 20 employees or fewer. It’s a very fragmented industry. And larger firms are more productive. Firms with 200 or more employees made 86 per cent more revenue per employee than firms with 5 to 19 people.)

So there are all these levers to get construction productivity moving. Now, as a thought experiment, hold planning regulations constant—you can’t advance the YIMBY agenda. You can only pull the other levers. If you could pull those other levers to get construction productivity moving, how much would that move the needle on housing supply? Or is supply basically stuck unless you first address planning regulations?

BRENNAN: I don’t have a neat answer about the relative proportions, but it is clearly a bit of both. Think of a basic supply-and-demand diagram.

If, at the margin, the supply curve is vertical—which is to say planning restrictions bind and you’re prohibited from building the extra unit—then theory suggests it really doesn’t matter how efficient the construction sector gets. All of that will just flow in additional rent to the supplier; it’s not going to increase quantity. It’s not going to increase volume.

I suspect that is the situation that confronts us in certain areas. Where there are restrictions on density in quite high-value areas, the supply curve is essentially close to vertical, so construction productivity is not going to be a thing that really moves the needle there.

There are no doubt other areas—because you do hear feedback from the construction sector: “It’s just not economical for us to build in particular areas,” i.e., the price of the product we would be building just won’t sell. There’s not a market for it.

That suggests—and maybe this is more in greenfields areas, or more in some dense-but-lower-value land areas—that the supply curve there is upward-sloping. There, you would expect that if you can shift the supply curve down or to the right—reduce cost—supply will increase. So it’s a bit of both.

The difference in quantum is that productivity in a sector like construction—or any sector—is going to tend to be pretty incremental year on year: 1.5 to 2 per cent, maybe it gets a bit more rapid if you get a big technological breakthrough, but generally hard grind and incremental.

Relaxing supply constraints could operate more quickly, if you’re prepared to do it. In the near term, it’s likely the supply constraints probably would have a more appreciable effect, if you were prepared to relax them, than the various channels of productivity growth that you mentioned.

WALKER: Interesting. Imagine we get rid of all the planning regulations that, say, Peter Tulip wants to scrap. Imagine that we also get labour productivity in construction moving back to some kind of reasonable growth rate.

What would the new constraint on housing supply be? I feel like at that point, it becomes more of a political constraint. Because if prices fall too much, too quickly, people lose a lot of equity and you maybe even risk a balance-sheet recession. At that margin, is that the new constraint on more supply?

KAPLAN: I don’t know. Is the thought experiment that we got productivity growth more broadly up, or just in construction?

WALKER: Let’s say just in the construction sector, and it’s a YIMBY utopia, so we can build wherever we like. Supply can accumulate much more rapidly than it does today.

Is it then a political-economy problem where we don’t want to bring prices down by too much, too quickly?

KAPLAN: There would be vested interests for that, for sure. If the supply curve is vertical—as Michael conjectures, which I think is right in certain areas—that suggests there are rents to be had if you can expand supply. Those rents are going to accrue to the builders who are going to build there.

The people who are going to lose are those currently accruing the rents—the current owners. In that situation, the constraint is the vested interests of that group and their political ability to wield them.

But that’s only one part of the country, when we think about those very high-density areas we’d like to make even denser. It would have less implication for smaller cities more generally.

BRENNAN: It is an interesting thought experiment. When you think about what currently drives opposition to density, the argument that it’s going to undermine property values doesn’t crop up a lot. It tends to be about amenity and neighbourhood character—shadowing, traffic—the sort of urban amenity issues.

That’s partly because we haven’t had a lot of success. So, in the world you imagine, it’s not impossible that you would start to get more explicit opposition. Sometimes the opposition maybe would be tacit and not reveal the true motive, but even honest opposition around, “This is going to kill our property values,” we don’t hear that a lot, but it’s not impossible you could hear that.

And it would— to Greg’s point—represent a transfer from incumbent property owners to would-be entrants, I guess, because part of making housing more affordable for entry is that the price comes down.

KAPLAN: I feel like there’s a long way to go in the sense that prices in the areas we’re talking about have gone up by a lot. And it’s not clear that we’re talking now about falls in prices—which is the sort of balance-sheet issue you’re concerned about. Maybe it’s slowing the growth in prices.

And there, there’s a lot of scope before you could make a compelling argument that there are stability concerns or macroprudential concerns from a big drop in housing prices.

WALKER: As a shorthand, let’s call the concerns about loss of home equity the “homevoter hypothesis.” The other stuff is, I guess, amenity concerns—that’s the “I don’t want noisy, ugly construction in my neighbourhood.”

Tell me if this is incorrect: the second set of concerns is currently what characterises most NIMBYs in reality; the first set is the mental model that federal politicians have of the average homeowner.

BRENNAN: That could be right. I think at the state and local level they’ve probably got the NIMBY mindset a little more in mind. It’s the controversy over densification and people’s cherished neighbourhood character changing.

But you could be right. There is, at the federal level, a bit of a tradition of—and former prime ministers and senior ministers have observed—“Nobody ever complains to me that their house is worth too much.”

WALKER: Yeah. The last two decades of Australian housing policy at the federal level have been bookended by leaders from both major parties making comments like that. There’s the famous Howard radio comment in 2004, and then last year there’s Clare O’Neil on Triple J.

Okay, to take this thought experiment one step further. (And this could be pretty difficult because we don’t have data and spreadsheets in front of us.) Say labour productivity growth over the past decade or decade and a half was, instead of the pretty lousy—what is it, 1% or whatever it’s been—closer to the 2% we had just after the reform era, at least in the market sector. So late ’90s, early 2000s.

How much more politically palatable would house price falls be if we’d had that stronger labour productivity growth? Presumably people would have higher incomes and be richer—does that make them more willing to accept losses in home equity?

KAPLAN: I’m pretty sceptical that it would change much.

WALKER: Why is that?

KAPLAN: Let me lay out a couple of things. One is: let’s go with your counterfactual—we had twice-as-fast productivity growth over the last 10 years. There’s no guarantee where that productivity growth is going to accrue.

Productivity growth is a very aggregate thing, and the distribution of how that plays out in the economy—there are many ways it could play out. It’s not obvious to me that the group you’re thinking of would be [the biggest beneficiary]. We need to think about what that productivity growth looks like and how it manifests in wage income and household income more broadly.

Second, if you look at the vested interests we were talking about earlier, for a large part that’s not a group of the population whose income sources are necessarily sensitive to the sort of labour productivity growth you’re talking about. There’s a lot of passive income, investment in second properties, and other wealth accumulation—superannuation and those sorts of assets—where it’s unclear that would shift the reliance away from home equity as a generator of wealth.

BRENNAN: I share that scepticism a bit. One observation is that although productivity growth has been pretty sluggish over the last 25 years, income growth has actually been pretty good by virtue of the terms of trade.

This is a totally unempirical claim, but here goes. When have Australians—when has the general mood or zeitgeist—suggested that Australians have felt most prosperous?

It’s an interesting thing to reflect on. We talk about the reform era of the ’80s and ’90s. My recollection living through it was that much of that time people didn’t feel particularly prosperous. Even the ’90s, with its rapid labour productivity and TFP growth, it’s not as though the headlines were telling a story of, “We’re really going well here.”

I think people did acknowledge a degree of prosperity around the middle part of the first decade of the 2000s, when the terms-of-trade boom really took off—that sense that the budget was in balance, there were tax cuts flowing, incomes seemed pretty high, the dollar was worth a lot. People are perhaps always a bit grudging, but there was more of a sense then that life felt pretty prosperous. And I don’t think it really translated into moving the needle on this sort of debate.

I think it’s tempting ex ante to say, “If we could get greater prosperity, maybe there’d be a greater acceptance of some of these hard choices.” I’m not sure in reality, or whether our expectations just adjust—I don’t know.

KAPLAN: It’s also not clear to me that faster wage growth wouldn’t translate into higher house prices…

WALKER: True.

BRENNAN: If there’s a scarcity constraint.

KAPLAN: …Yeah, given the constraints we’re talking about.

WALKER: Okay, so one final housing question. Do you both buy the standard YIMBY argument that densifying our major cities—particularly Sydney and Melbourne—would lead to big gains in productivity?

KAPLAN: I don’t. I can’t speak for Michael. There are cities that would benefit from densification, but I’m sceptical about the Sydney–Melbourne argument.

So, what’s the number—like 40%?

WALKER: About 40% of Australia’s population is in Sydney and Melbourne.

KAPLAN: Yeah. It’s hard for me to see where those productivity gains would come from. When I think about spatial productivity, I think about competing forces between agglomeration on one hand—which is what you’re getting at, what the YIMBY movement is getting at—versus congestion on the other hand.

WALKER: And what do you mean by congestion?

KAPLAN: Congestion, in economic terms, is sort of the negative of agglomeration, and the way economists would model this is they’d stick a minus sign in front of it.

What’s agglomeration? It’s the idea that when you put more people in the same place, as a result of the number of people, each individual person is more productive, able to produce more.

Congestion is: more people makes it harder for any one individual person to produce.

WALKER: Before you move on, can we unpack the channels by which those gains of agglomeration work? There’s better matching in the labour market, but are we also including things like knowledge spillovers?

KAPLAN: Yeah.

WALKER: Okay. So the existence of cities like New York, London, and San Francisco—and the enormous knowledge spillovers there—doesn’t the existence of those cities automatically refute the claim that we’re not going to get net gains of agglomeration from densifying Sydney and Melbourne?

KAPLAN: I don’t think so. Firstly, it’s not obvious to me that the relative size of London, relative to the rest of the UK, is a net benefit for the UK. It might be good for London; I’m not sure it’s necessarily good for the UK. So even in this discussion, we should ask whether we’re trying to improve the welfare of Australians or the welfare of people living in Sydney and Melbourne.

Let’s put that aside. Second, Sydney has strong geographic constraints—which are real. Melbourne less so—Michael knows more about this than me. But it’s not obvious to me that it’s feasible in a practical way.

You mentioned two agglomeration channels—firms and workers can better match to each other, and new ideas and developments can spill over and be used by firms in the same sorts of industries. I think there’s another one at a more social level: where do people want to locate, set up their lives, and make plans for the future?

That requires things beyond just jobs. It requires infrastructure, healthcare systems, good schools, social networks, and a broad range of groups people can form community with and connections with. Those come from reaching a critical size. Those benefits from agglomeration are going to exist at different scales than some of the other benefits.

You could tell a story—and I’m going to make these numbers up—that there’s something very different between living in a city with 2,000 people and a city with 200,000 people along those dimensions, that are different from going from 200,000 to two million, or two million to 20 million.

So when I talk about the difference between potential gains from increasing supply in Sydney and Melbourne versus other parts of Australia, I’m thinking about the difference in the gain in going from a five-million-person city to a 10-million-person city, versus growing some Australian cities that are a couple of hundred thousand people to a couple of million people.

Some of what I’m saying is about where those potential agglomeration gains will come from, and some is about the congestion force, which works in the opposite direction.

WALKER: So YIMBY-Greg would focus more on densifying places like Canberra?

KAPLAN: I think that’s a great idea.

WALKER: Is there anything more you want to say on the congestion?

KAPLAN: I think a lot of people forget about the congestion. You mentioned New York and London—these are really big cities—but there are some really difficult things about living in New York and London. I’ve lived in both of those cities. I’m very happy that I live in Chicago now and not in New York or London, in terms of where I am in my life with young kids and a family.

I also know there are other very big cities of similar size that are nowhere near as productive as New York and London. We can talk about very large cities in Asia where people will tell you it’s the congestion that makes it very difficult when you don’t have the right transport and other infrastructure to realise agglomeration gains. So it’s not obvious to me that we should just make Sydney and Melbourne bigger because they’re currently more productive—therefore put more resources there.

BRENNAN: I share a bit of the scepticism. Up front, it feels to me the productivity argument is secondary to the housing-affordability argument.

WALKER: Which is more of a welfare thing, right?

BRENNAN: I think that’s right. The strongest YIMBY argument for densification is that it will reduce the cost of housing—make housing more accessible and more affordable.

Is there a productivity gain there? Potentially.

One interesting question—I’m pondering both New York and London now in my mind—I think Greg’s right that sometimes these agglomeration benefits may operate over slightly different scales.

You’re right to separate them out, because conceptually they are distinct: the matching benefit—which is about, “If I can get a bunch of employers and employees together in the same location…”—and they spontaneously have pretty good incentives to do this, right—if a firm is located within, call it, a 40-minute commute for two million workers or five million workers or whatever, it allows them to pick a very specialised worker for a niche role, and vice versa for the worker. That’s the matching benefit.

The knowledge spillover is something more mysterious: it’s this idea that ideas transmit by virtue, often, of physical proximity and interaction.

My gut is that the matching benefit can operate over the scale of an urban area. The knowledge spillover feels like something that operates over a much smaller geographic scale. You know, it’s about a cluster of workers and firms within a smaller area.

Most of these precincts that emerge spontaneously—or that government sometimes tries to create—are motivated by that much smaller-scale agglomeration. So I think it’s an interesting question: at what scale do you get these effects?

You might be able to devise transport solutions and a degree of density such that you better link a whole lot of people to firms and jobs and get the matching benefit, even if we’re not, in all cases, dense enough to get some of those knowledge-spillover benefits.

WALKER: I’ve started this off by taking us all the way down the construction, housing, urban-economics rabbit hole. But I want to step back and talk about growth and productivity more broadly, starting with some measurement issues and the metrics we might want to be optimising for.

Greg, some of these questions might be more in your wheelhouse, but Michael, obviously feel free to jump in at any point.

We’ll start with the metrics and measurement issues. Firstly, GDP: Greg, could you outline what you think are the most important limitations of GDP as a metric? There are many, but which ones give you the most pause?

KAPLAN: I’m going to give you the economist answer: it depends. And if you’ll let me take a step even further back, I naturally want to ask, “Metric for what?” Right?

I think there’s a big question: what is it we’re trying to do, what is it we’re trying to measure, and why are we measuring GDP?

GDP was not invented as a metric to measure welfare. It was invented to measure how much stuff we produce. That turns out to be pretty well correlated with welfare—and there’s a reason we tend to look at it, which I’ll go into—but let me make two points from the outset.

One is that, ultimately if what we’re interested in is welfare, that is a distributional issue. There are lots of different people (there’s a “who”), and there are lots of different things those people are doing. There you and me, and then there’s stuff I consume, goods I buy, time I spend, my physical and mental health—there’s all sorts of aspects of me. So we need to aggregate across the things that contribute to my welfare, and then across people.

Then there’s the “how”: how do we do that aggregation? There isn’t going to be one right answer from the outset.

Let me make the case for GDP, because before we talk about the limitations I think it’s important to be clear about what it does well. It does two things really well. First, it’s well-defined. And we can measure it. If we want a metric, those are two pretty good features. It’s easy to come up with hypothetical things you might want to do, but we want to be able to compare across countries, across time, in a consistent way, and to do that we need to be able to measure. So GDP ticks that box.

Second, it turns out that it’s very highly correlated—both across time and across countries—with all of the other things that go into our welfare. That’s a statement about correlation, not causation, but it is a way to see what’s going on. It’s hard to find examples—and of course we can cherry-pick some—where GDP doesn’t grow but welfare does, and vice versa, over long periods or across very different countries.

What are the limitations?

The biggest ones for thinking about welfare are these. First, what is GDP? It’s trying to measure how much stuff is produced in a particular place over a period of time. We produce a lot of stuff, and GDP counts things that may or may not be relevant for our welfare.

We’re trying to aggregate. And how do we do that? We aggregate using market prices—a dollar of this and a dollar of that, we add them up, and that’s two dollars of stuff. Whether that dollar is spent on weapons or on pastries is completely irrelevant from the point of view of GDP. So when looking at fluctuations in GDP or across countries, that’s a big issue.

Second is the distribution issue. Fundamentally, GDP is an aggregate and doesn’t necessarily tell you anything about the way in which those resources are distributed across people.

Finally, it only measures things you can attach a market price to, because we have to add different types of goods up. So it’s going to leave out things like health, mental health, the environment, and all the standard non-market items you read about in a textbook.

WALKER: Okay, great. Next: is there a “growth accounting in two minutes for economists”?

KAPLAN: I can try.

WALKER: Okay, let’s try. Let’s see what happens.

KAPLAN: So here’s one way of thinking about how much stuff we produce (GDP).

We produce stuff by combining capital—things that are reproducible, like factories, maybe land to some extent, and labour (people). It’s a very, what I’d call, Victorian-England approach to production; industrial revolution. That’s also the limitation, but if you want to understand growth accounting, think about: we build a factory, we hire some workers, they come to work at the factory, and widgets pop out the other side.

We want to understand why, over time, we produce more widgets—people call that growth accounting—and why some places produce more widgets than other places—some call that development accounting.

There are only three reasons why one place could produce more than another. They either have more factories (capital), they have more people showing up at those factories (labour), or they’re able—for the same amount of people going to the same amount of factories for the same time—to produce more widgets. That last thing is productivity. Technically, productivity is how much you can produce with the inputs you put in, inputs being capital and labour.

Growth accounting tries to ask, over time, how much of the increase in output comes from more capital, more workers, and how much from getting better at using them. Starting in the late 1950s, with a paper by Bob Solow, people collected the data to do that. The classic finding has been that capital accumulation plays some role, but a surprisingly large amount of growth—over the 20th-century United States and across countries—has to do not with the amount of capital, but with how we use it: productivity.

WALKER: When we were chatting on the phone on Friday, you mentioned that what we think of as capital in the 21st century can blur the distinction between capital (K) in our production function and A, which is total factor productivity. Anything worth putting on the table there?

KAPLAN: It’s good to remember the world doesn’t look like that Victorian English factory, and there are a lot of other inputs to production today.

There are many other forms of capital than just factories. The classic one people figured out very soon after we started doing these calculations was that some capital is embodied in people—we call that human capital.

If you adjust some of those estimates for differences across countries not just in how many workers there are, but how much capital is embodied in them by virtue of education, it accounts for a big chunk of those differences.

Where that’s playing out today is in forms of intangible capital: institutional know-how, organisational capital, IT infrastructure and software—things that last over time but aren’t captured by the traditional factory approach to capital. Even things like data, models, or algorithms are a form of capital: we can reuse them and they help us to produce. These things are difficult to adjust for, because how do you measure them? They don’t have easily attached market prices, but people have tried.

If you look at the last 30 years of US growth (and probably something similar for Australia), and take conventional capital, roughly half of growth came from capital deepening—more capital—and half from using that capital more effectively—productivity.

Once you incorporate broader, intangible, more modern forms of capital, it’s more like two-thirds/one-third.

WALKER: Oh, so two-thirds capital deepening?

KAPLAN: Two-thirds capital deepening, one-third productivity.

At some level this is semantics, and as we’re having this conversation it’s worth keeping in mind. If a factory has better data in its machines and better software, and as a result it can produce more stuff—and that was more expensive to build that factory versus the old one—do we want to say that we produce more stuff because we put more inputs in or because we can use those inputs better?

They’re two sides of the same coin. A lot of what we call productivity is embodied in the capital we use. That calculation is picking up that some of the growth we’ve seen isn’t a magic mystery economists call “A” or “Z” sticking out the front of a production function; it’s embodied in the inputs we use. And in order to realise it, we have to invest in those productivity-embodied inputs—like intangible capital.

WALKER: Yeah. And just to inject my own commentary here (I’ve been brushing up on this over the past few days): I think it’s important to clarify that A, or total factor productivity, isn’t equivalent to technology, although people often talk as if it is. A good intuition pump, or something I found helpful for getting this point, is just to notice that across some industries or countries, TFP can have negative growth from time to time.

If TFP was just technology, that would mean that those industries were suffering some kind of technical regress.

But that’s not plausible. As one economist—I can’t remember who—put it, we don’t forget blueprints.

So there must be something else to TFP, which is efficiency, know-how, tacit knowledge.

KAPLAN: This is a fantastic point and indicative of a broader issue to keep in mind in these discussions. On the one hand, we’ve got measurement: we collect data, get numbers, and compute things—those are the numbers we compare.

Then economists use models—simplified versions of the world with clear, well-defined constructs—and we try to map our world onto that simple model. I’ve been going back and forth between the two in this discussion even.

The simplest model—the Victorian-England one—says output (Y) equals A (productivity or technology) multiplied by capital (K) and labour (L).

In that world, yeah, technology and productivity are the same thing because it’s a pretty simple world. But no one thinks that’s what the real world looks like.

In the real world we just go out and measure stuff, and that measurement process is going to take you quite far away from the object in the model.

So when we talk about productivity, are we seeing it through the lens of the model—is it a thing like technology—or do we mean “What you get if you count up a firm’s revenue and divide it by the number of employees”? Those are the two objects. The one we have in our mind is somewhere in between, but it’s not on the table. It’s either the thing you measure or the thing in the theory.

WALKER: A question for both of you. If you had to pick just one north-star metric that policymakers should be optimising for, what would it be?

Imagine you time-travel or you go into a coma, you wake up in 20 years’ time…Say Anthony Albanese time-travels 20 years into the future—what’s the first thing he’s asking for? Is it real GDP per capita, or what?

KAPLAN: Charlie Wheelan, in his Naked Economics books, does exactly that thought experiment.

WALKER: Oh really? I haven’t read them. What was his answer?

KAPLAN: I think the title of the chapter is basically “When You Wake Up From a Coma, What Should You Ask?” and his answer is GDP.

WALKER: Just GDP?

KAPLAN: GDP per capita or something.

But I’m going to be annoying for a minute.

WALKER: Go ahead.

KAPLAN: You ask the best questions, Joe, but I just don’t think that’s a question for policymakers to be answering. Because if you go back to where I started—which is “What is it that we’re trying to do?”—we’re trying to improve the welfare of some group of people—it might be Australians, people more broadly, this generation, future generations. Ultimately it’s an aggregation exercise and it’s a big thing.

The mistake we make is exactly to look for one metric and then debate whether it’s the right metric. Of course it’s the wrong metric. My advice to policymakers is: keep your eye on a bunch of different things. If you choose one north-star and focus on it, you’ll end up maximising that, and (remember) “that” is not a real thing—it’s just a measurement you took.

BRENNAN: All good points. Look, if you absolutely had to have one, and it’s ex post—looking backwards over the last 20 years—I’d prefer something that incorporates income, like real disposable income growth per capita, as your best proxy for welfare.

Ex ante, looking forward, in a stylised world where you can maximise one thing, you could do worse than GDP per capita. Of course that is stylised and not right. And it might be subject to the odd big thing—so it might be that, in the next twenty years, rational policymakers would say, “Well, the climate transition is something which has to be done, and that may or may not add to GDP per capita (partly because in reducing emissions we’re reducing a cost that has not traditionally been counted in GDP)”, and therefore a rise in GDP per capita is not the main game, because it’s subject to these other big things.

But in normal times, if we’re looking forward, I know how it comes across, but what else is there? There’s no other good broad-based measure that’s a reasonable approximation for how much better off we are in material terms.

KAPLAN: It’s strange to me because GDP is not a fundamental thing—it’s a measurement we came up with in the 1930s. We could measure whatever we want.

BRENNAN: Yeah. So what did policymakers do before then? What did Pitt the Younger regard as his fundamental object? Beating the French, I guess.

Communities and their leaders must have had other, perhaps intangible, indicators or objects in mind. It’s an interesting question, and it reflects something about how mechanistic we’ve become in the way we think about policy and the way we think about success.

WALKER: Yeah. Conditional on caring about productivity growth, should policymakers look more at labour productivity or TFP?

KAPLAN: These are two very different things, so let’s get them on the table. It depends, again, why you’re looking at productivity growth. If you want a proxy for something that resembles household welfare, labour productivity is much closer to that: how much stuff we produce divided by some measure of the effort or work we put into producing it. It’s close to GDP per capita—output on top, people on the bottom. So if you want a euphemism for GDP per capita or stuff per person, then labour productivity [is the appropriate metric].

But if what you really want is a measure of how effectively or efficiently we’re producing stuff—because we think having more stuff enables us to do more—then TFP is a much better measure of how effectively we’re producing. If what we’re trying to measure is productivity—efficiency—TFP captures that better. But it’s not necessarily a good measure of welfare.

You were the Productivity Commissioner, [Michael,] what would you do?

BRENNAN: In theory, TFP is the purer measure because it distills how much labour productivity growth did we get from capital deepening. And capital is not costless. If you go back to the early Austrian economists, they observed there was a lot of labour effectively congealed in capital—it’s just a more roundabout mode of production.

But the measurement issues are just so great, which is part of why you observe the odd fall in measured TFP and why it looks very volatile. The challenge is measuring capital services; that’s what you’ve really got to measure—the capital input as distinct even from the capital stock. That’s difficult, stylised, and open to interpretation.

So as a basic heuristic, labour productivity—GDP per hour worked—isn’t perfect (it’s subject to its own measurement issues), but it’s probably a little less subject to the vagaries of really difficult measurement.

KAPLAN: Would you say that’s true even in a resource-producing economy like Australia? You have big movements in resource prices; we use our mines more; labour productivity looks like it moves around a lot, because the level of labour input doesn’t change too much.

BRENNAN: Yeah, it is complicated in very capital-intensive industries. TFP will bounce around a lot in those industries because of big capital investment cycles, and you can see troughs in TFP as a result.

KAPLAN: So you get movements in TFP because of the investment cycle. You get movements in labour productivity because of the prices moving around—utilisation.

BRENNAN: In theory, labour productivity should be fully deflated for the price of the relevant commodity. Ultimately it is a proxy for a physical measure—hours of labour and other physical inputs in, physical output out, and the change in those things—so in theory it abstracts from commodity prices. Not from second-round effects, though: high prices can draw resources into the sector and affect measured productivity.

This goes to my point about income versus GDP per capita. GDP is a production-based measure, whereas income is what we get for it. The experience of the last 25 years in Australia has really confirmed the importance of prices in the Australian story. If you think of the three Ps of the Intergenerational Report—population, participation, productivity—there’s kind of a fourth P: price. Prices have been incredibly important to our success.

Now, that makes it sound like it all just good fortune—and there is a bit of good fortune in this. We happened to be a mining producer at a time when China rose and had big demand for our resources. There is something to be said, though, for the speed and nimbleness with which Australia was able to respond to that with minimal overall economic disruption. But prices are guiding many of the allocative decisions within the Australian economy in a way that productivity actually isn’t. So understanding the role of prices both in allocation but also overall welfare is important.

WALKER: Any other measurement issues you want to put on the table before we move on?

KAPLAN: There’s one that we should mention. When we measure productivity, we often look at GDP per worker as a decent whole-economy proxy for how much stuff people produce.

But we often go further than that and apply something similar to the individual firm level. You often will hear discussions about “firm-level productivity”, with the idea being that if you want to understand how productivity works at the aggregate level, let’s look deeper into the individual firms in the economy.

There I think it becomes more challenging, because what we actually measure is something like the amount of revenue a firm produces divided by the number of employees—so revenue per worker. It feels similar to doing it at the aggregate, but it’s actually very different. There are many more reasons why a firm’s revenue per worker could differ from another’s, or grow over time, that get washed out in the aggregate. So while both are imperfect proxies, it’s a much less perfect proxy at the firm level. And maybe we can talk about the reasons why we should be careful about inferring too much from the data on so-called firm-level productivity for policy and thinking about the sources of overall aggregate productivity.

WALKER: Give me a couple of quick examples or reasons of why we should be careful there.

KAPLAN: Revenue per worker is ultimately how much revenue you produce per employee. If I’m a high-revenue-per-worker firm and you’re low, there are many reasons why.

It could be that we both produce exactly the same stuff and the same amount of stuff, but I’m more effective at producing it—so it really is a productivity gain. But it could also be that I have invested a different amount of capital in my firm than you have. It could be that we operate in different product markets with different prices. It could be that you’re able to charge a higher mark-up over costs relative to your competitors. It could be that your marginal cost of production—how much it would cost you to expand production—is different to mine.

Most of the time it’s that we’re producing different stuff. It’s only a very small subset of the economy where we can actually compare two firms and say they produce exactly the same good and therefore any difference in revenue per worker, we can have a clear interpretation of it. Most of the time we’re just looking at dollars of stuff. And they’re produced in very different ways, so it becomes much harder to know whether it is something about productivity or something about production or something about the market.

Can I give one example?

WALKER: Yeah.

KAPLAN: Take software. If you’re a software company, the marginal cost of production in terms of workers is pretty small, right? You sell an extra piece of software, it doesn’t require any more workers.

So if you were able to expand that, what does that tell you about productivity? Nothing in terms of the technology interpretation we gave earlier, but it certainly is a measured productivity increase. It’s just capturing something very different from looking at a firm actually increasing its technology—using higher technology that allows it to produce more stuff for each employee.

WALKER: Great. Okay, so Michael, if you were Jim Chalmers listening to this conversation, and you bought all of Greg’s measurement critiques, is there anything you’d do differently tomorrow?

BRENNAN: Not really, no.

I’m sure he has a high respect for Greg, but I think the question is: does any of it change your fundamental strategy? Greg’s right: you take these headline aggregates with a grain of salt. They’re not the be-all and end-all.

They’re a pretty good heuristic, but they’re not everything. The question is whether you can replace something like GDP per capita or real incomes per capita or whatever with some other holistic, perfectly aggregated—but somehow more all-encompassing—measure. And the answer is you can’t. There is the Human Development Index and other things that attempt to bring in a measure for life expectancy, equality of income, and other things. I think you’re better off just having that aggregate and some other things you really care about.

Have a look at life expectancy. Have a look at whether it’s your Gini coefficient or some other measure of the equality of the distribution of income. Have a look at incarceration rates among disadvantaged communities—whatever it is that you want to highlight. But keep them fairly segmented as a dashboard of indicators rather than trying to heroically amalgamate these—do another version of GDP but with a broader measure of welfare.

I think where it really comes into sharp relief is more at the micro level. Obviously there are particular policy areas where prices don’t fully reflect the costs or benefits of the activity concerned. That’s where policymakers would want to move away from the price-equals-marginal-cost assumption. That’s obviously true for carbon emissions, road congestion, and a whole bunch of other things. So policy has to be open to where welfare or wellbeing departs from what’s measurable or observed. But I don’t think it’s fruitful to try to bring it all together into some kind of magical index.

WALKER: Okay. I just want to quickly level-set, and I think we can get through these next two topics in five minutes maximum. First, I want to characterise the Australian economy—especially for any international listeners. Second, I’ll give some quick statistics to provide a sort of health check on the Australian economy.

This is another question for you, Michael. Could you share some stylised facts about the Australian economy? Say you had a friend who was an economist, but maybe they’re an American or someone overseas who doesn’t know anything about Australia—they call you up. What are the first three to five bullet points you’d share about Australia?

BRENNAN: I think it’s a great question because I think fundamentally Australia is quite a distinctive developed economy. It’s quite different to much of the rest of the developed world.

There are three industries where Australia is a big outlier in the sense that we are hugely overweight in those industries as a share of our overall economy. One is mining. Very few developed economies have a big mining industry. Most developed economies have traditionally had a big manufacturing industry. Australia has not. We had more of a manufacturing industry, but it was always small and it has diminished. But mining is a big deal in Australia relative to other developed economies—but it’s something we share in common with more emerging economies, right?

That means we have big exposure to commodity prices, which leads to a degree of volatility in our budget, for example. That’s a macroeconomic management and fiscal management issue that’s a little distinct for Australia.

The second industry where we are overweight is financial services, because we have effectively a privatised pension system. We have this large superannuation system—compulsory contributions made by employers on behalf of their workers that get invested on their behalf. So we’ve now got a funds-management industry exceeding $4 trillion—well in excess of GDP and well in excess of the capitalisation of our stock exchange. This is significant, and it’s an outlier in terms of financial services as a share of GDP.

The third is construction. Because we’re a high-immigration, we’re a high-population-growth country—it’s not often well understood, even in Australia, how much of an outlier we are in that respect—we’ve had population growth at times of 1.6, 1.7, 1.8%. Again, in the developed world, that is unusual. So construction is a larger share of our overall economy.

Accompanying those latter two—superannuation and housing as really significant assets that characterise household balance sheets—I think that is particularly, if not unique, then at least distinct to Australia.

The only other things I’d point to are a little more intangible but go to the policy and political culture of Australia. Two things I’d point out.

One is we traditionally have had—unlike a lot of the developed world, though maybe we share this a bit with the Nordics and East Asia—a culture of fiscal prudence, for want of a better term: a view that governments should balance the budget and debt should be low. In much of the developed world that’s not really a feature of the political culture at all. Maybe it has fragmented a bit in Australia, but traditionally this has been a key litmus test by which the success of governments has been measured—can you balance the budget?

WALKER: Do you know where that comes from?

BRENNAN: Maybe we’ve had a measure of success on that metric and it just became embedded. But it’s certainly noticeably different to, say, the United States, and even I’d say much of Western Europe, right?

And the third and final thing is that our social safety net looks a bit different. In one sense, we’ve got quite widespread, for example, labour-market regulation—we have a relatively high minimum wage as a share of the average wage compared to the rest of the world. In another sense, though, our welfare safety net is highly targeted—and that’s a little different again to much of the OECD, particularly where they have unemployment-insurance arrangements which are contributory and everyone’s paying in and can draw down in the event of job loss. Our social safety net is highly means-tested, and I think there is a very strong culture of means testing in Australia. Again, I think it’s fragmenting a bit, but traditionally the idea that social assistance should primarily go to low-income households—to people who really “need it”—has been a really important part of the political culture.

So, in the absence of unemployment insurance and perhaps given the great Aussie love of housing, there is a sense in which, for many purposes, Australia is a bit of a self-insurance economy. You ride out the volatilities of income or job loss often through the offset account—which is a distinctly Australian thing—the offset or the redraw on the house, drawing down on some of that accumulated wealth or whatever. Maybe this is part of the reason why there’s so much politics in it—it’s the buffer, it’s the cushion.

I think there’s a whole research agenda around modes of self-insurance in the Australian economy, and it might be a little distinctive in Australia.

WALKER: Neat summary. That’s great. Okay—my job now is to provide a quick status update on the health of the Australian economy. This is maybe more for our international listeners, and again, to the extent I reference charts we’ll put these up in the video version of the episode.

For those who don’t know, Australia’s a country of about 27.5 million people. Last year our GDP was about US$1.75 trillion, or about A$2.6 trillion.

In terms of GDP per capita, I think we rank about ninth in the OECD on a purchasing-power-parity basis.

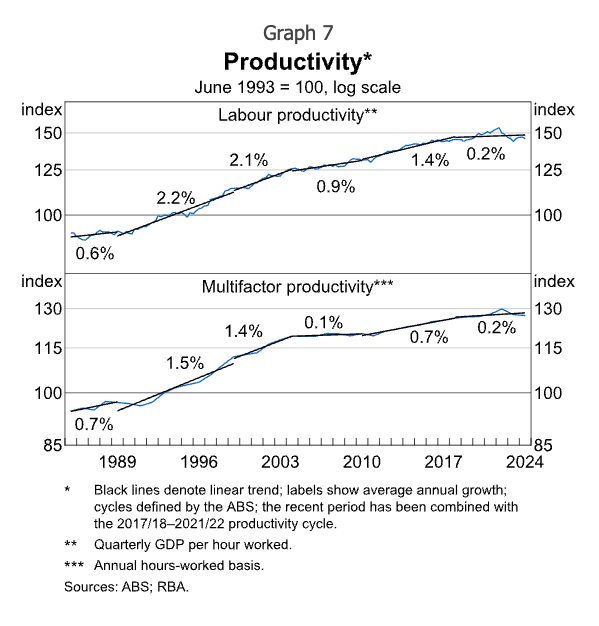

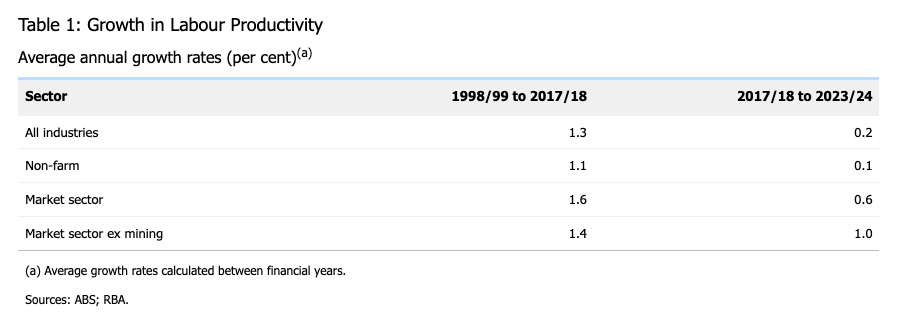

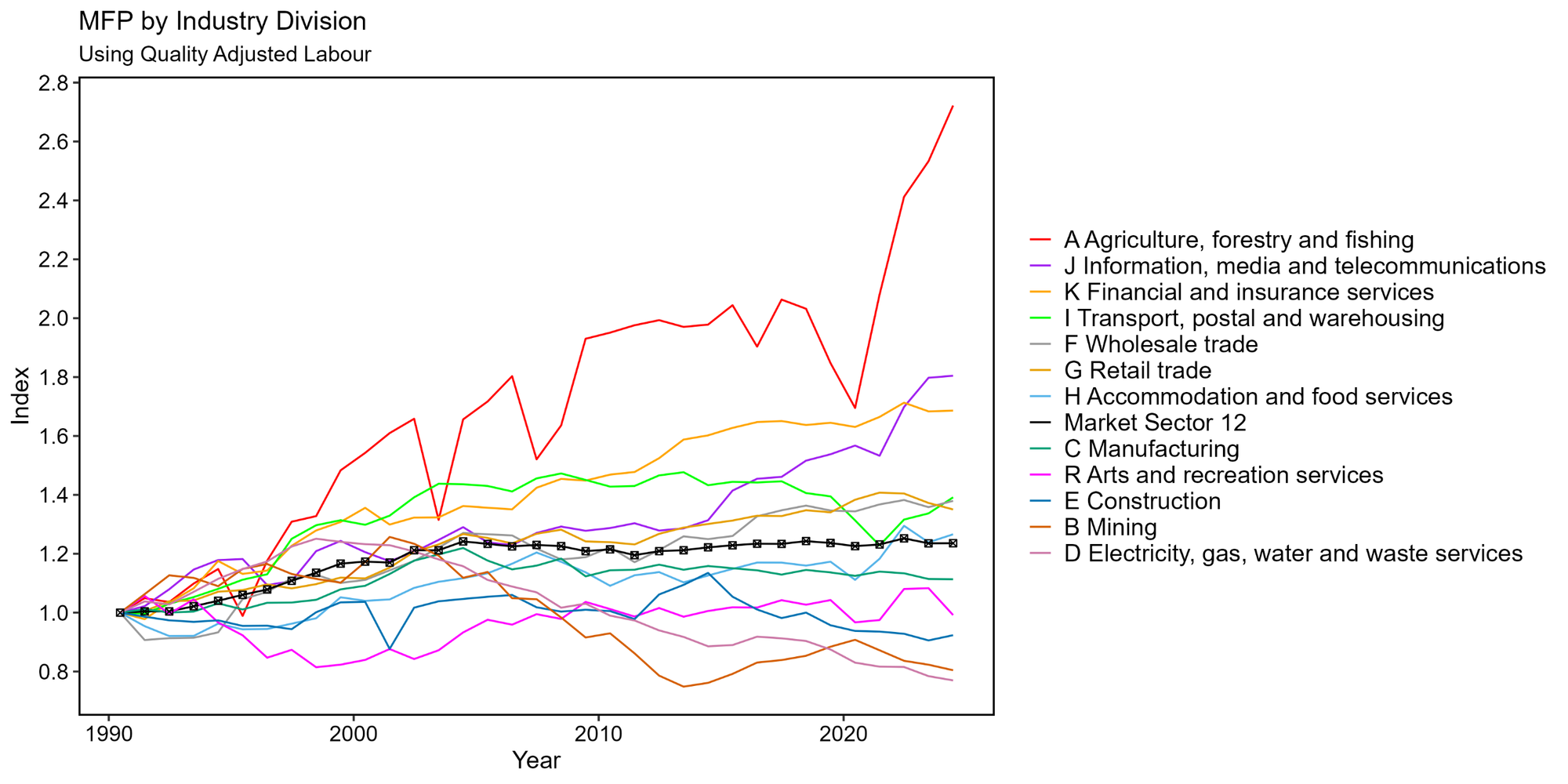

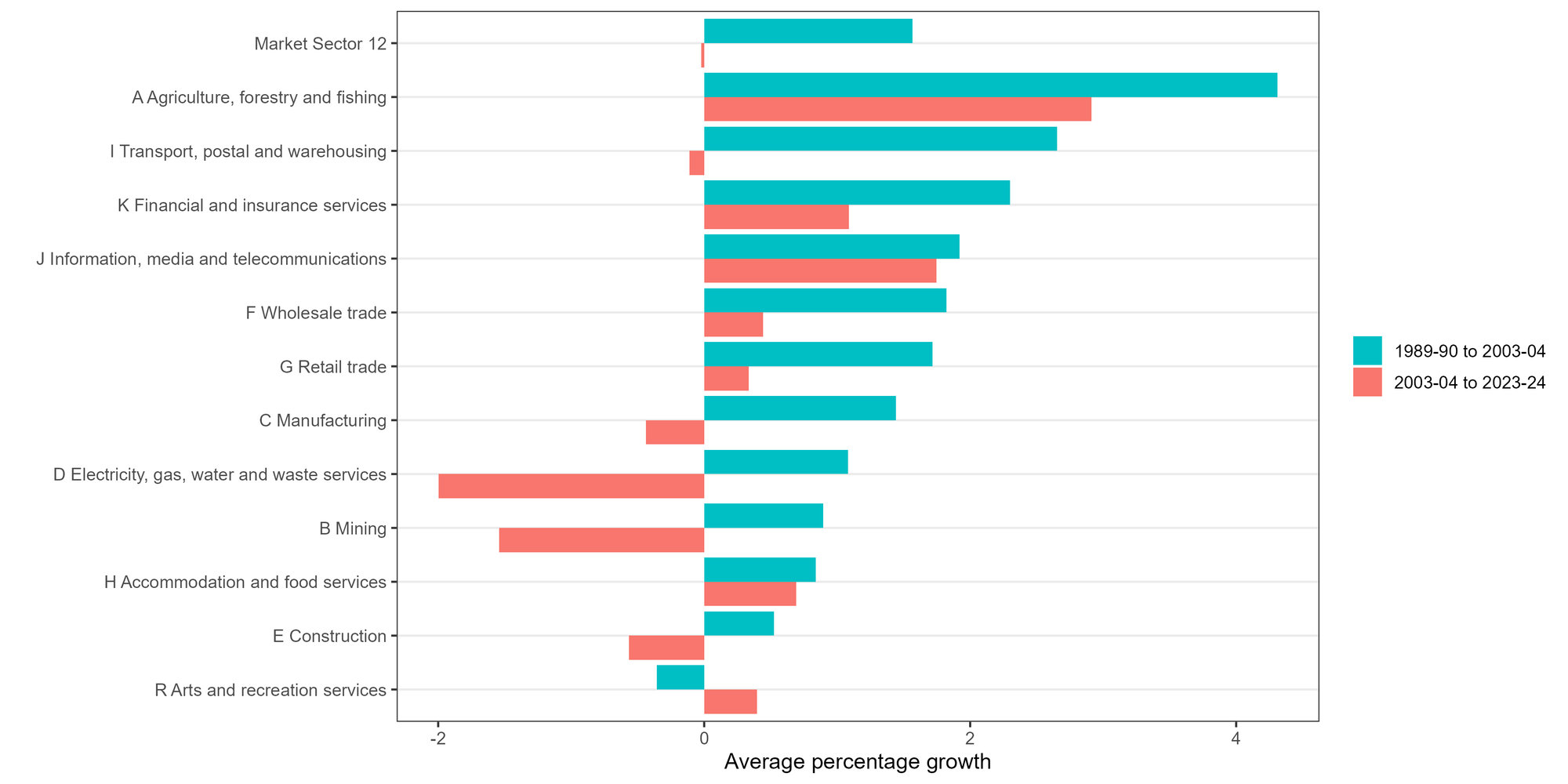

Labour-productivity and TFP growth have been underwhelming, to say the least. Since the 2017–18 fiscal year, both labour-productivity and TFP growth have been only 0.2% per year.

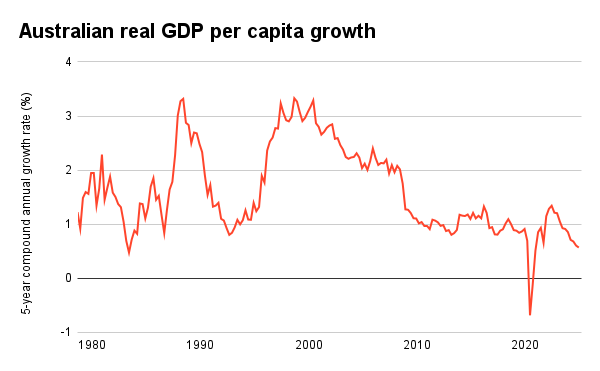

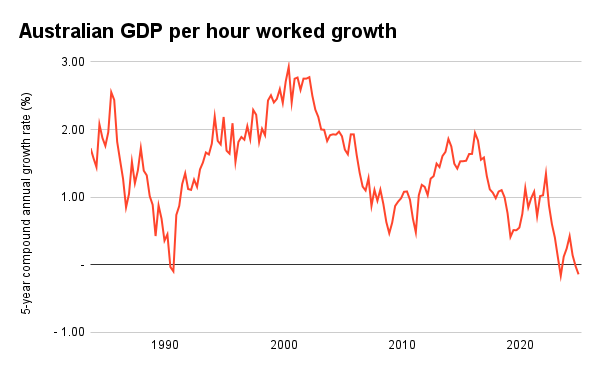

Real GDP per capita growth has been declining, you could say, since the turn of the century. This is a chart looking at the five-year compound annual growth rate.

Labour productivity has also been stagnating—again, you could say since the turn of the century.

And that is the RBA’s stuff—this table is probably an easier way to draw the comparison against the earlier period.

For the market sector, in the two decades to the 2017–18 fiscal year, labour-productivity growth was 1.6% per year. But since 2017–18, it’s been only 0.6%.

Anything else you would add to that?

BRENNAN: I guess just to return to the recurring theme in relation to GDP—average real GDP per capita growth—which was high around the early 2000s and then steadily declined. There was a part of that period where income growth, nonetheless, was pretty strong.

WALKER: Yeah, because of the terms of trade.

BRENNAN: Because of the terms of trade.

In level terms, whilst it has fluctuated, the terms of trade are materially higher than they were in the 1990s, and that has, in effect, been the underpinnings of prosperity largely, given the poor contribution from productivity growth.

WALKER: Yep. Okay, so let’s talk about goals and growth regimes. I have a couple of quick questions on what we could be aiming for and then what the downside might look like. I’ve another chart, which I’ll, again, put up in the video.

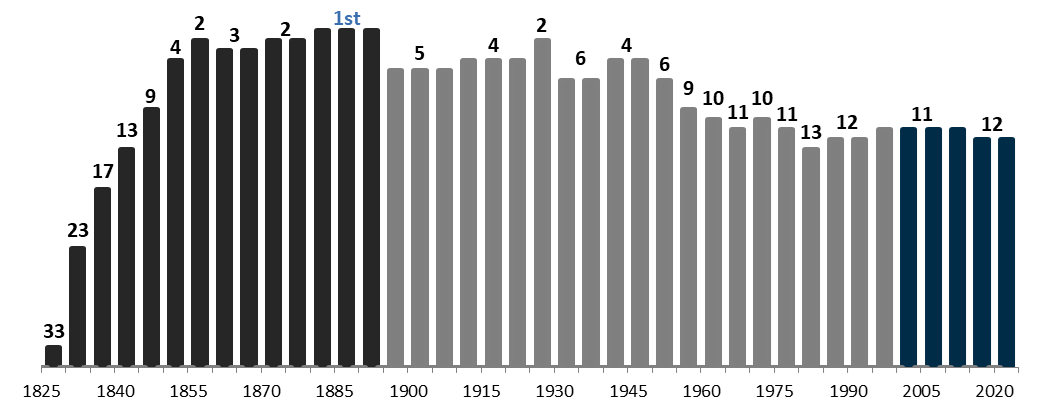

This is Australia’s global rank measured by purchasing-power-parity-adjusted GDP per capita over the last two centuries. As economic historians know, Australia, for a time, was the richest country on Earth in the late 19th century.

Maybe this is a silly question, but as a thought experiment I wanted to ask: what would it take to reclaim that top rank?

BRENNAN: Well, it's interesting how it came about. I mean, a couple of big causal factors were growth of the pastoral industry—land was the big thing that became pretty plentiful, obviously at the cost of dispossession of an indigenous population. But that input was able to be expanded significantly, and substantial income growth came on the back of the wool industry and then gold from the 1850s onwards.

When I reflect on Ian McLean's book Why Australia Prospered, he makes a point that the gold rush resulted in much more sustained prosperity than one might think. It is consistent with a gold rush. So I think a couple of big industries really provided some tailwinds.

I think it was a period of global growth and openness, and we were linked to a massively expanding market in the United Kingdom, which was going through a period of substantial income growth and industrialisation.

But yeah, it is an interesting thing to ponder, just the economic success of the 19th century, particularly given that the big income growth that occurred in Western Europe really didn’t start until the early 1800s. So, it wasn’t as though those who came in the 1780s had necessarily already experienced that big surge in income growth that then characterised Western Europe and later the United States.

I think also there were some good institutional choices that were made early on. There was a big debate about whether to in effect convert the pastoral leases that had been issued to squatters in western New South Wales into freehold title. There was a lot of resistance to that, rightly, and I think it in many ways prevented the creation of a sort of oligarchic pastoral class. I think that’s part of the story of the success over that period: a kind of a sense of democracy, a sense of maintaining institutions that were fairly egalitarian. In economic terms, that also paid dividends.

Could we achieve it again?

I mean, that logic partly reflects... When did we slide down the rankings? We slid down the rankings partly because some other countries developed. And that’s a great thing. Singapore, Taiwan, Japan, Germany—although neither of those, I think, outrank us at the moment in the per capita stakes. But it was important in that post-war period that much of the world recovered.

When you look at our relative performance, it’s sort of hard to escape the conclusion that the 19th century was largely characterised by agriculture, a bit of mining. Much of the 20th century by manufacturing, and Australia didn’t really catch the manufacturing wave in the same way that other economies did. For whatever reason, it just wasn’t our thing in the way that agriculture and mining were.

When agriculture was the biggest industry in the world, we were number one. When manufacturing was the biggest industry in the world, we were further down.

KAPLAN: But we were still number ten.

BRENNAN: Yeah, that’s true.

KAPLAN: I think it's easy to look at 150 years ago and say, "We were number one. Wow, it’s a failure since then." I think we also need to look at some of the other countries' performance over that period.

Argentina is the one that comes to mind, but there are others that have taken another path from the same position.

WALKER: Right. Do we know what the highest growth regimes are that have been sustained by other frontier economies in recent decades?

KAPLAN: Well, I think the key word there is frontier, right?

WALKER: Yeah.

KAPLAN: Yeah. So, the 2% number seems, over long periods of time, like a pretty hard number to get around.

WALKER: 2% real GDP growth.

KAPLAN: That’s the long-term number for the US.

WALKER: The US, right.

KAPLAN: You would think about that as being the frontier. Now, I may be less optimistic than others that that’s sustainable over long periods of time. If you put it in a much broader context, it’s a pretty special period.

But yeah, numbers like 5% seem difficult.

WALKER: Okay. So, what do you think is the most ambitious growth regime that Australia could plausibly aim for?

KAPLAN: Should we be aiming for growth regimes? I mean, it feels to me a little bit like a five-year plan.

These numbers are outputs, not inputs, right? What we should aim for is: let’s remove all the impediments that we place on people producing in the most productive way.

Let’s foster whatever policies we can where government has a role to play, and see where we land up.

That seems to be a much more productive approach than to start putting targets in terms of these outcomes.

WALKER: Okay, let me reframe the question. Say we make Michael Brennan and Greg Kaplan benevolent social planners—omnipotent social planners.

BRENNAN: Disaster.

KAPLAN: That’s gonna be a negative number. [laughs]

WALKER: And you implement the full suite of your agenda and remove all the impediments you’re worried about. What kind of ballpark or range do you think we could get to in terms of our real GDP growth?

BRENNAN: I will come at a number just to humour you, Joe, because I’m a pleaser, but there’s a lot of truth in what Greg says and there’s a lot of contingency in it. When you look over the broad sweep of history at what’s driven productivity growth, a lot of it is technology broadly conceived—the pace of technological change. Of course, that includes everything from high-end, complex technologies right through to the “invention” of the shipping container—which is not really an invention at all but it’s an economic innovation, it was a coordination issue, but it’s led to huge efficiency and trade, which has been a huge source of productivity growth for countries like Australia. It’s the pace of those sorts of things that come along, and then it’s an economy’s ability to adapt to that and adopt it.

You think of Robert Gordon’s thesis. It might just be that the pace of technological change has slowed and that’s going to place a limit on how fast productivity growth can be, irrespective of the policy and institutional settings that a country’s got.

But logically you would think, if you were after a number you would go back to the sorts of numbers we achieved during the second half of the 1990s as being ballpark. You feel if you’ve got your policy settings right, your broad institutions of openness and adaptability, and you’ve got a technology that’s there for the taking in the way ICT perhaps was in the ‘90s (and potentially AI today and maybe other things)—that feels like the sort of growth rate that’s not unreasonable for an economy to aspire.

WALKER: What the the growth rate?

BRENNAN: Labour productivity growth of these orders of magnitude.

WALKER: 1-2% [per year].

BRENNAN: Yeah, 1-2%.

WALKER: Got it. Okay, again this question might be better answered by a spreadsheet than a podcast, but say we continue with our disappointing productivity growth of 0.2% per year, do you know how much GDP we’ll miss out on roughly in a decade’s time, relative to a counterfactual of more like 1-2%?

KAPLAN: So you’re asking what the compound difference to the power of labour share?

WALKER: Greg can you just quickly work that out in your head? [laughs]

KAPLAN: I don’t know the number but it’s substantial.

WALKER: Over ten years?

KAPLAN: Yeah.

WALKER: It might be like 30, 40, 50%, something like that.

KAPLAN: Yeah. Back of the envelope: what are we talking—1.5% per year? Over 10 years, that’s 20% or so.

WALKER: So it’s significant.

KAPLAN: Yeah.

WALKER: Okay, so let’s talk about what’s causing the productivity crisis, and then some different ideas to fix it. Just as a starting point, tell me what’s wrong with this view: the punchline is that the crisis is—if not non-existent—at least greatly overstated, and the argument relies on three points. Dietrich Vollrath, the American economist, is most famous for making this argument in the American context. I’m just stealing it and applying it to the Australian context.

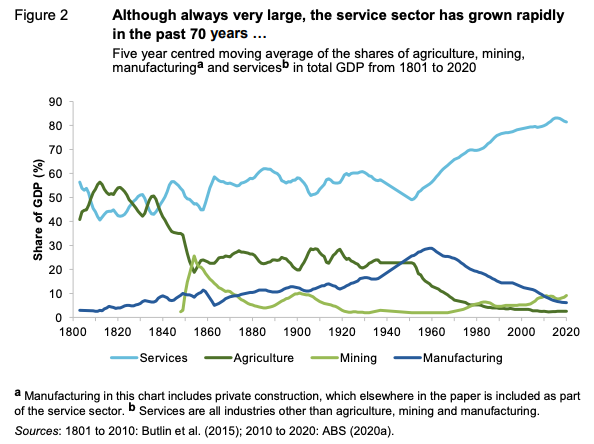

The first step in the argument is: services industries tend to be lower-productivity than goods industries because of this intrinsic quality whereby services tend to involve labour. And eking out productivity gains from labour is difficult; it has diminishing returns because you’re constrained by the scope of people’s time and attention. The classic example is listening to a string quartet: if they’re playing a 30-minute piece of music, you don’t want to hear it in 12 minutes. That 30 minutes is going to be pretty fixed across the centuries or the decades.

Second, the price of services, as a result of that first point, will tend to rise relative to goods—also known as Baumol’s cost disease.

Third, more economic activity will shift into services, because our demand for services is income-elastic, whereas our demand for goods is income-inelastic.

We see this in the data. If you look at the size of Australia’s services sector as a value-added share of GDP, it’s grown rapidly in the last several decades. At the moment it’s about 80% of GDP. This chart is from the Productivity Commission in 2021—Michael, this was when you were chair, I think. So I’m giving you your own research. Look at this research I’ve done! [laughs]

In this view, the productivity slowdown just reflects a shift in consumption from goods—which we’ve got really good at producing—to services, which are lower productivity. And that slowdown is just an artefact of how productivity is measured. We wouldn’t be better off if we reversed it, so everyone just needs to calm down and carry on. There’s no productivity crisis; there’s no need for huge roundtables. This is just what happens to a mature economy.

So, what’s wrong with that view?

KAPLAN: I think it’s a perfectly reasonable hypothesis and every premise there makes sense. But it’s an empirical question at the end of the day. I’d get Michael’s view, but my understanding is it’s just not borne out in the data. It’s clearly part of it—we’re shifting towards low-productivity sectors, and some of those sectors are also outside of the market, which has contributed—but my understanding is that if we look within sectors, there have been big productivity slowdowns even within those sectors, within services sectors.

You could do a within–between decomposition of changes in productivity. My understanding is that most of the change is within sectors, not across sectors. So yes—but it just doesn’t account, empirically, for a huge fraction. I know we’ve done some work at e61 on this, and I know the RBA has done some as well.

BRENNAN: Yeah we’ve done a bit on the rise of the care economy. It does two things. The shift in the composition of the workforce towards sectors with low levels of productivity obviously has a compositional effect—it reduces overall productivity growth. But there’s also a question about the ongoing productivity growth in these sectors as well. I think the cost-disease story is pretty compelling as a set of stylised facts as a starting point, but I wouldn’t read into it that therefore there’s “no problem”.

It helps qualify it a bit, but to me it characterises the nature of the challenge. The string quartet is interesting because it goes to whether services can be automated—can we achieve productivity growth in these services? The string quartet is instructive because the original intent of that metaphor was: you can’t just automate the cellist. It’s not like manufacturing where you strip out labour and replace it with capital. You still need four people in a string quartet.

What is interesting is we’ve had technological advancements that mean people can hear that string quartet—a billion people could hear that string quartet, rather than a hundred sitting in an auditorium.

KAPLAN: That’s exactly my issue.

WALKER: So it’s a failure of imagination to say that services really do depend on labour as much as they historically have?

KAPLAN: Well, no—it’s about how you measure output. Baumol’s idea was brilliant. He’s saying the measure of output there is the 30 seconds of producing the music out to the world.

An alternative potential measure of output would be the receipt of that music by a set of ears.

And so now how much you produce depends on the size of the auditorium. In which case one would say that maybe that sector actually has had more productivity growth than almost any other sector you can think of.

WALKER: Okay. But you can pick other examples where there are constraints. Teachers and doctors…

BRENNAN: Yeah, absolutely.

KAPLAN: Of course. But the point is to say that innovation in services is not impossible.

And if the one thing we've learned from the AI changes that we're seeing is that, yeah, that's going to happen. Hard to predict where and how much, but it’s not a God-given truth that services can’t be produced more effectively.

BRENNAN: I don't know how far this gets us, but just bear with me for a moment. The string quartet—good example. Think of a lot of household chores…

It's interesting to reflect: in one sense, the service economy was probably bigger in the 19th century than it is today, right? The share of time spent on people doing stuff. It was a service-dominated economy that, as this blue line reflects here, services got replaced by goods, in a way, via manufacturing. So a lot of the service of, you know, having four people play a string quartet for you in the auditorium, that got replaced by a record and a record player. So, the ability of manufacturing to step in and create a substitute for the service or, in the case of household chores, a dishwasher and a washing machine…The manufacturing industry came in and manufacturing these things got cheaper and cheaper over time because we were able to automate that process.

Part of what's gone on in more recent times—I think of the music example—is we've actually gone back towards a service in a sense. You no longer buy CDs, records, that sort of thing. We now have phones and it’s a streaming service. The point being maybe you can't forever manufacture away what is fundamentally a service. I don’t know. That’s an unproven thesis, right? But interesting to think about.

The thing that I think is relevant to the services sector, and this is, again, a forward-looking thought experiment, but I look at agriculture here. It’s extraordinary to think in the 19th century that was 60% of the economy—the measured economy, at least.

At the turn of the century, 1900, okay, so it's down to about 25%, but it was about 25% of the workforce as well.

It's now about, what, 4 or 5% of the workforce? The output is hugely increased. So we are producing vastly more wheat and fiber and food than we were in the 1900s. But we're doing it with many fewer people, and that’s part of the “cost disease” story—that's the labor that was freed up by those highly efficient, highly productive industries to flow into other things that we decided we wanted, many of which are services.

So it is interesting, I guess, to reflect now. You think of our biggest employing industries, like health and social assistance, education, some of these, and think, "Okay, so would we plausibly expect over the next 100 years that they're going to have a big productivity surge that's going to translate into shedding labor at the same rate, where it's gonna go into other sectors?"

And it might, but at this point in time, it's hard to envisage. But maybe that's always true. Maybe it's always hard to envisage how labor could be massively liberated.

I think this is partly your point about elasticity. If health improves a lot in quality, we're just still going to want more because it's just a natural thing. Why wouldn’t you? More life, more quality life. Whereas some of these goods are more inelastic. Maybe once they get cheaper, you want something different. So I think it is an interesting question. Are we going to see the same pattern in some of our modern service sectors that we observed in, say, agricultural and manufacturing?

KAPLAN: Let me just add one observation. Underlying this (there's a blue line here [in the graph], the services line), the two biggest sectors there are health services and financial services, maybe education services as well.

Health and financial services are two sectors where the productivity measurement issues are probably most pronounced. Michael focused on the denominator, the labor coming in and out. I think the bigger challenge is the numerator: output. How do you define output in the financial services sector? It's very, very difficult.

It's some form of revenue. It is producing some value, by maybe more efficiently allocating capital, allowing people to insure over time. Those are very abstract concepts that are very hard to measure. The same thing goes with healthcare. Ultimately, what we're measuring there is going to be something with dollars on the top. But if we're getting better health outcomes, that's something that's very hard to get into the productivity statistics. Would you agree with that?

BRENNAN: Absolutely, yeah. See, I kind of agree with the basic premise that you're putting, Joe, but it’s unclear how big the problem is.

But at least I would say this: if productivity growth looks different in the future to what it looked like in the past—including that more of it is quality, hard to observe, the demand for these services pretty elastic, etcetera—then I think it does have implications for some of the things that we have asked of productivity growth. Like, for example, productivity growth has been the way that our fiscal arithmetic has added up, right? It’s allowed governments to expand service delivery at a rate that exceeds population growth and inflation and still have the revenue to cover it because revenues will grow roughly in line with the economy. So, if there's productivity growth, it sort of gives you a bit of fiscal wherewithal.

The story you're telling, if it’s right and it’s not clear that we're going to get big, real cost reductions in these services, these things aren’t going to become radically cheaper over time, then some of that fiscal arithmetic becomes challenging. So even if it’s not a problem in terms of overall well-being and that sort of thing, it just changes the nature of what dividend we're going to get from productivity growth. I think that’s still a challenge.

WALKER: Just quickly so I'm super clear, the services / Baumol's cost disease story is true, but the effect just isn't large enough to explain all or most of Australia's productivity slowdown?

BRENNAN: Yeah, I think it's part of the story.

WALKER: Part of the story, but not the dominant explanation.

BRENNAN: Yeah, I think that's probably right.

WALKER: Okay. Just while we're on the topic of services, what do you see as the lowest-hanging fruit for getting productivity or quality improvements in services?

BRENNAN: If I think about that conceptually—and this is me playing in my benign dictatorship or whatever, so now I've got complete, not just control over government, but I'm actually running the economy 1940s-Soviet-era-style—when I think about emerging technologies, it's got its political challenges, got its implementation challenges, but it's really not impossible to envisage use cases in health and education for AI that are pretty obviously productivity enhancing, potentially labour saving, quality enhancing.

It's much harder in disability maybe and in aged care and in childcare. There are still services where it's gonna be difficult, I think, to achieve the sort of productivity growth that we observed in agriculture and mining. There would be political and stakeholder difficulties, but I would've thought there is very substantial scope for technological adoption in those sectors.

WALKER: I mean, not to be too crass, but if you think about what a GP does, which is essentially like pattern matching and then giving a fairly pro forma prescription—a lot of that you can see being at least assisted by, if not substituted for, by things like LLMs.

BRENNAN: Yeah, I think you could see a world in which a GP could achieve very similar health outcomes in less time for a larger group of patients.

WALKER: Yeah.

KAPLAN: I want to ask a question about this, and maybe I misunderstood the question.

So that's really an answer that's really about how I'd love the economy to look as opposed to what maybe we should do as governments. I'm not sure if that's what you're trying to get at, but thinking about that sort of harder question of, okay, so how do we enable that? What is the role of government in getting us to that?